On February 22 in Hanoi, the National Economics University organized the Policy Dialogue of the first quarter of 2024 with the theme “30 years of Vietnam’s development: Looking back at the past and responding to new challenges”. The dialogue identified development challenges in the new context and proposed policy recommendations for Vietnam to achieve sustainable growth and become a high-income country.

A TOUGH “GATE,” LACK OF GROWTH MOMENTUM

Looking back at Vietnam’s achievements in the past three decades, Professor Pham Hong Chuong, Rector of the National Economics University, believes that Vietnam has transformed from an economy reliant on imports to one of the world’s largest open economies with an export-oriented direction. Vietnam has also transitioned from a low-income agricultural economy to a new industrialized economy with low to moderate income.

According to Professor Ngo Thang Loi, National Economics University, after 30 years of innovation (1990 – 2020), Vietnam has consistently set high social development goals and surpassed them. Notably, Vietnam exceeded the GDP per capita target for 2020 (USD 3,000 per capita) by reaching USD 3,521 per capita; the Human Development Index (HDI) is at 0.704, higher than the target of 0.7…

Looking back on this period, Mr. Loi believes that Vietnam has successfully overcome 2/3 of the challenges. Vietnam has surpassed the challenge of food security achieved in the period 1991-2000 and has essentially established the foundation for an industrialized nation. The second challenge Vietnam has overcome is being removed from the list of low-middle-income countries.

“The third challenge that Vietnam has yet to overcome is becoming an industrialized country by 2020,” Mr. Loi emphasized.

Building on this success, Vietnam aims to become a “High-income developing country with a modern industrial sector” by 2030 and a “High-income developed country” by 2045.

“To achieve this goal, the economy will need to grow at an average annual rate of 7% over the next 22 years. Vietnam also aims for greener and more comprehensive growth, committing to reduce methane emissions by 30% and halt deforestation by 2030, while achieving net-zero emissions by 2050. Several major trends are shaping Vietnam’s future,” Mr. Chuong highlighted.

According to the overall assessment of many economists and researchers, the period from 2024 to 2030 is a decisive period for Vietnam’s transformation into an industrialized country in accordance with Vietnam’s Socioeconomic Development Strategy for the period 2021-2030. This is an important milestone that opens up many development opportunities for our economy, especially under the influence of globalization, international economic integration, and the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

On the path to a new development period, Vietnam is facing many challenges. Professor Pham Hong Chuong believes that Vietnam’s population is rapidly aging and wages are increasing. Global trade is declining, and businesses need to comply with stricter environmental and social requirements.

In addition, environmental degradation, climate change, and automation are increasing. The Covid-19 pandemic and political instability in many parts of the world present unprecedented challenges. These challenges can undermine the progress towards development goals.

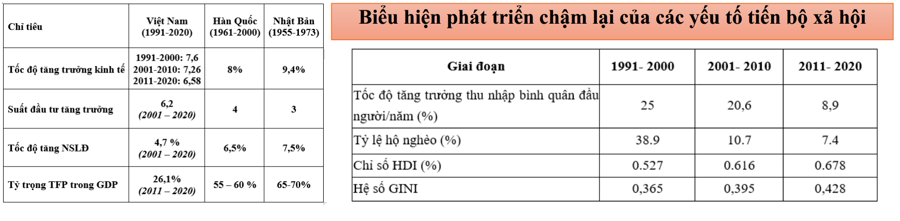

Similarly, the growth momentum of Vietnam is slowing down over time and not keeping up with other countries like South Korea and Japan during a similar period when Vietnam was in a similar situation.

“The growth rate is decreasing, and it is not strong enough to create breakthroughs in social progress. The quality of growth is improving but at a slower pace, limiting the income growth of the economy,” stated Mr. Loi.

In addition, there are many signs of a slowdown in social progress, and income inequality is increasing during the rapid growth process. In slower-developing regions with low income, there is a stronger correlation between growth and social justice.

The Gini coefficient, an indicator of income inequality, shows a decrease in areas with faster growth and an increase in areas with slower growth.

Explaining the reasons for these challenges, according to Mr. Loi, many issues stem from the development model when the manifestations of the old development model are no longer suitable, such as the extensive development model and the equal distribution policy.

LEAP FORWARD, AVOIDING THE MIDDLE-INCOME TRAP

Information from the dialogue shows that Vietnam’s Gross National Income (GNI) per capita in 2022 is USD 3,939, approaching the high-middle-income level.

According to Professor Ngo Thang Loi, the country’s development goals are set very high and are quite optimistic. By 2030 (the 100th anniversary of the Party’s establishment), Vietnam aims to be among the high-middle-income countries and by 2045 (the 100th anniversary of the country’s establishment) to be a high-income country.

Regarding the development trend of the middle-class society, the World Bank and the Ministry of Planning and Investment predict that the middle-class population in Vietnam is rapidly increasing. By 2035, the middle-class proportion will be 50% (currently at 16.5%).

Professor Tran Van Tho from Waseda University (Japan) also shares the concerns: “The issue is whether Vietnam can transition from a high-middle-income country to a high-income country by 2045. What are the conditions for Vietnam to avoid the middle-income trap and continue sustainable development over the next two decades?”

According to Mr. Tho’s analysis, in the initial stages, the economy has the characteristics of surplus labor and low-cost labor shifting from agriculture to industry as the industrialization process begins. Countries in this situation will export labor-intensive industrial goods and easily achieve average income levels.

When wages increase and cheap labor is scarce, countries must shift the industrial structure to produce higher value-added industrial goods with higher levels of technology, capital, or skilled labor.

Many neighboring countries such as Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, after a long time, are still struggling to move beyond the middle-income level.

“Failure to make this transition will lead to the middle-income trap for these countries,” Mr. Tho noted.

Therefore, to avoid the middle-income trap at this turning point, countries need industrial policies that encourage and support businesses in investing in areas with high value-added and make efforts in training high-quality human resources.

He suggested five policies to develop the economy to a high-income level. First, expansion, depth, and industrial transformation. Policies to promote entrepreneurship should be implemented so that domestic enterprises, including small and medium-sized enterprises, can take advantage of market and technological opportunities to invest in industrial production.

In addition, efforts to replace imports from China and South Korea and introduce new types of FDI policies.

Second, increase overall productivity by transforming family-based production and business units into formal, organized enterprises.

Third, improve factors of production and the business environment.

Fourth, strengthen the supply of skilled labor. Mr. Tho believes that the lack of skilled labor is a serious issue. Therefore, increasing the supply of skilled labor is an urgent task to promote industrialization and structural transformation of industries.

“Connecting skilled interns in Japan with FDI and domestic businesses planning to invest in the production of high-value-added products,” Mr. Tho suggested.

Fifth, Vietnam needs to prepare for a new era of growth based on innovation for the 2030s and beyond.

“In the context of globalization, structural transformation, and increasing productivity will make Vietnam competitive in the international market. This is the condition for Vietnam to avoid being the sandwiched position, meaning a country that is unable to compete with a later country with lower production costs but has not yet competed with an earlier country,” emphasized Mr. Tho.

According to the World Bank’s income classification, countries are divided into 4 groups corresponding to the average per capita income.

Specifically, low-income economies have a GNI per capita below USD 1,035; lower-middle-income economies have an average per capita income ranging from USD 1,036 to USD 4,045; upper-middle-income economies have an average per capita income ranging from USD 4,046 to USD 12,535; high-income economies have an average per capita income above USD 12,536.