At the moment, commodity traders are competing for data on sugar harvests in Brazil or rainfall figures in Vietnam’s rice growing regions – but most of them overlook the corresponding figures for tea, the world’s second most popular beverage after water.

On the futures market, traders agree to buy a commodity at a price in the future, and thus increase the risk or profit of the commodity on delivery, which may then be at a price lower or higher than the price they agreed to pay.

Of course, the futures market plays a crucial role in both agriculture and finance – allowing farmers to secure income even in poor harvest seasons, while investors can diversify their portfolios by counter-cyclical assets.

As a result, the futures market exists for most food commodities, minerals, including steel, gold, coffee, sugar, orange juice, and wheat. But not tea.

To understand why, we have to delve into the world of tea.

Tea, which includes all kinds of flowers, wild grasses, fruits, and leaves, is soaked in hot water and sipped. But as a commodity, tea is defined only as the dried leaves of the Camellia sinensis plant, a plant species originating from black and green tea, excluding herbal teas.

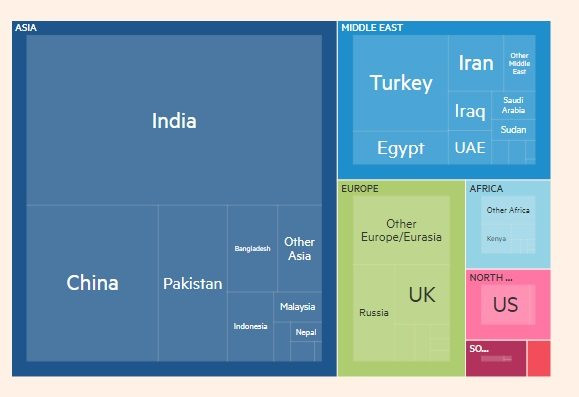

Camellia sinensis is a plant that can grow in different seasons, climates, and conditions worldwide. China dominates the production of green tea, but black tea is the main crop in India, Sri Lanka, and some parts of China. Both types are widely consumed as black and green tea are equally popular worldwide.

Tea has become more popular after Covid-19 as people pay more attention to health. Now, in any café in developed countries, you can order a matcha latte or a chai latte. Industry experts predict that both production and consumption will accelerate in the next 10 years.

This also brings us to the first reason why there is no tea futures market: it is a too good a crop.

Look at its rival, coffee. It is seasonal, only in certain climates can coffee plants grow, and farmers can’t predict annual yields due to uncertainty about rainfall, temperature, and humidity.

Tea is not like that. It grows all year round, at various altitudes and climates. Therefore, farmers can easily predict annual yields. Even in the face of abnormal phenomena that reduce yield, fluctuations only exist for a short period because tea can be harvested almost immediately.

The second core reason is its diversity.

Tea is not a standardized product. There are many colors, and many types of tea can be made using the same leaves. However, for a futures market product to exist, the commodity needs to be standardized (for example, you can’t differentiate between wheat from the United States and Ukraine). Coffee accomplishes this by dividing into two “references” – Robusta and Arabica.

Nevertheless, there are many valid reasons to create a tea futures market, and many people support it. The FAO has even held summits and issued reports on the potential for the future market of Indian and Chinese tea.

The price of coffee has fluctuated many times since 2018, while tea has remained relatively stable – but this will not last forever.

Despite the countless varieties of tea, some references can be created for common black and green teas – sold to companies such as Lipton and Twinnings. Premium teas such as Oolong or rare teas can be classified using a similar premium system to specialty coffees.

Some markets have tried to standardize tea. In India, most packers require tea to be ground into consistent particles to reduce the volume of tea bags, called CTC tea. CTC (crush, tear, curl) tea accounts for 90% of the Indian tea market and 64% of the global tea market and can mostly replace each other.

Even with some artisanal teas, some countries have established a standardized grading system as with other items. Depending on the size of the leaves and the degree of maturity when harvested, tea in India and Sri Lanka is graded on a scale from “dust” to premium “pekoe” (meaning big, beautiful leaves).

To make a futures market appear, some things need to be done. Auctions, where producers and packers set tea prices for the daily market, need to be standardized and transparent, instead of being a one-time agreement between farmers and producers.

Global tea consumption in 2022 by country.

Then, interest rate and financial contracts need to be available to farmers – which seems to be beginning.

Finally, an intermediary needs to establish a trading floor where investors can start buying futures contracts.

But there is another barrier; although tea is increasingly popular worldwide, domestic markets are actually the main motivation for major producers.

Unlike coffee, which has a global supply chain – growing in developing countries, roasting and consuming in Europe, North America – tea is consumed mainly in domestic markets: only 37% is exported compared to 72% of roasted coffee. Major tea-producing countries such as China, India, and Turkey primarily serve large domestic markets. Only Kenya, Sri Lanka, and some other countries export a significant amount of tea to developed countries.

Therefore, tea needs to be popularized further in developed countries to form a futures market.

Tea is Vietnam’s top 5 commodity in terms of reserves volume. In 2023, Vietnam’s tea exports reached 121,000 tons, worth 211 million USD, down 17% and 11% respectively compared to the same period last year. This is also the year with the lowest export volume in 7 years.

The average price of exported tea last year was 1,737 USD per ton, an increase of over 7% compared to 2022, but this price level was still only 67% of the average tea export price in the world

Source: FT