The highly anticipated Thai Summit Group tops the list of companies Bangkok investors are eagerly awaiting to go public. The company has signed supply deals with all major Chinese electric vehicle manufacturers setting up shop in Thailand.

This family-owned auto parts manufacturer considered going public a decade ago but scrapped the plan when political unrest made market conditions unfavorable.

In an interview with Nikkei Asia in September, Senior Vice President Chanapun Juangroongruangkit stated that the company would remain private for the time being. This is likely to continue until her generation is no longer in control.

Senior Vice President Chanapun Juangroongruangkit, a key figure in the company’s future plans.

However, at 48 years old, Chanapun, the eldest child of the founders, cannot postpone decisions about the company’s future indefinitely, like many other business dynasties.

While the old adage states that “wealth doesn’t last past the third generation,” Southeast Asia’s relatively young business dynasties are challenging this “curse” as many are in the process of transitioning from second to third-generation management, a shift that is significant not only for family dynamics but also for the markets they dominate.

According to Credit Suisse, approximately 60% of listed companies in Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand are family-owned. In these businesses, family members hold executive or board chair roles or control at least 5% of the shares.

Half of the companies in Credit Suisse’s 2023 global Family 1000 report are in the Asia-Pacific region, excluding Japan, followed by Europe with 24% and North America with 15%.

Without a succession plan, a family’s business assets and control are at risk as the number of heirs increases with each generation. This makes the business vulnerable to a takeover if some family members sell their shares or if the family’s reputation is damaged in the event of bitter litigation among relatives.

“If you just rely on inheritance law, the natural consequence is fragmented ownership,” says Marleen Dieleman, a professor at the IMD business school in Singapore and an advisor to family-owned companies on succession planning.

Fragmented ownership can also result in successors having less power than the founder. In the broader Asia-Pacific region, family-owned companies, based on compound annual growth rates, outperformed non-family businesses by 3.3% from 2006 to 2023. But this premium applied to earlier generations, reflecting the strong growth in the early stages of the business ventures.

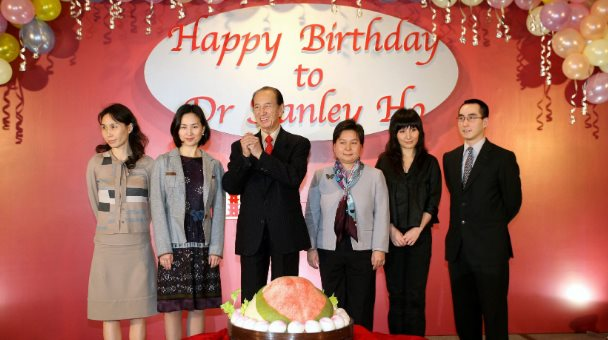

In January 2019, the market share and stock price of SJM Holdings, a listed company in Hong Kong, were declining, but they turned around when Pansy Ho formed an alliance with major shareholders to gain control from her father Stanley Ho’s fourth wife.

Stanley Ho, the Macao casino tycoon, at one of his birthday parties.

In the Philippines, the Tan family’s succession was disrupted by the sudden death of Lucio Tan Jr., known as Bong, the 53-year-old son of Fortune Tobacco founder Lucio Tan. Four years later, in 2023, Mr. Tan appointed his 30-year-old grandson, Lucio Tan III, to take over some parts of the empire, including Philippine Airlines.

In contrast, Lee Shin Cheng, the founder of IOI, a Malaysian palm oil producer, prepared for succession from 2014, facilitating a smooth transition to his sons, Lee Yeow Chor and Lee Yeow Seng, when he passed away in 2019. The eldest son, Yeow Chor, became the CEO of the group’s traditional palm oil business, while Yeow Seng took over the company’s real estate development arm.

Following the Lee family’s example, many Southeast Asian families are adopting constitutions or charters that govern how the family makes decisions, including appointing leaders, who can work in the company, and how members are compensated.

Thailand’s Central Group is known for having a charter and a family council. The group is currently in its third generation of leadership, including Tos Chirathivat, the group’s CEO and chairman. His cousins Wallaya and Thirayuth are CEOs of the group’s listed subsidiaries, Central Pattana, a real estate developer, and Centara Hotels, respectively.

However, the group has also brought in outside professionals and foreigners to help manage its listed segments. This often occurs when the business becomes too complex, or the next generation is uninterested or incapable of running operations, or the family wants to focus on entrepreneurship and building new businesses rather than management, according to Dieleman.

“Fast-growing companies don’t tend to create stable organizations. They are very lean and rely on the power of the top person,” she said. “Building that organization will make it easier for the next generation to take over.”

AC Mobility, a Philippine distributor of electric vehicles and developer of charging stations, is led by 33-year-old Jaime Alfonso Zobel de Ayala, an heir to the Ayala Group, a rare Southeast Asian family conglomerate established in the 19th century. In Malaysia, Ruth Yeoh, the daughter of YTL Corp. Chairman Francis Yeoh, heads the carbon credit and sustainability development arm of the utility conglomerate.

In its most recent study of family-owned listed companies on the Singapore Exchange, DBS Bank found that family-owned companies had higher returns on assets than non-family-owned companies because most families have a long-term vision for planning and continuity in leadership.

“Having a family leader or face is actually beneficial. It creates trust because the management is not driven by compensation but by family values,” Dieleman said.

Family-owned companies also have a longer track record with other stakeholders, including lenders, brokers, and investors. “This gives them better access to different types of capital and debt financing in the fixed-income market,” said Asadej Kongsiri, chairman of the Stock Exchange of Thailand.

Whether family control leads to greater transparency and stronger governance standards remains a subject of debate. According to Credit Suisse, family-owned companies are more likely to have dual-class shares than non-family-owned companies.

However, DBS’s study of Singapore-listed companies found that family-owned companies enhanced their disclosures during challenging periods to protect the family’s reputation. The number of independent directors exceeded the number of executive and non-executive directors on the boards of both family-owned and non-family-owned companies, but they held fewer board seats in family-owned companies.

Christian Stewart, the founder of Family Legacy Asia, a Hong Kong-based consulting firm, said that family-owned companies could empower more independent directors, not just to reassure minority shareholders but also to serve as a bridge between family members in management roles and their non-related relatives.

“It’s important to have directors who are trusted by the family shareholders but remain objective and commercially savvy enough to act as a bridge between the family chairman and family members who are not involved in the organization,” Stewart said.

Independent directors are even more critical when there is no clear succession plan in place. This is the case with Robert Kuok, the 101-year-old Malaysian “sugar king” and founder of Kerry Holdings, a Hong Kong-listed company that owns Shangri-La Hotels and Resorts.

Kuok has not yet announced a formal succession plan, but his children and grandchildren hold leadership roles within the Kuok Group, including his sons Khoon Ho, 73, and Khoon Ean, 69, and his daughter Hui Kwong, 46.

Source: Nikkei

What Does the International Press Say About VinFast’s Achievement as Vietnam’s No.1 Brand?

“The Green Revolution’s Trailblazer”, “A Pioneer”, and “A Testament to Vietnamese Determination” – these are just a few ways international media has described VinFast’s remarkable journey to becoming Vietnam’s number one automotive brand. In a short span of time, VinFast has not only captured the hearts of Vietnamese drivers but has also left its fossil fuel-dependent competitors in the dust.

The Rise of Vietnam’s Economic Power: From Lagging Behind to Surpassing Neighbours?

In 1989, Vietnam’s GDP (PPP) stood at approximately $83 billion. This figure lagged behind its regional peers; it was only two-thirds the size of Malaysia’s GDP (PPP), half that of the Philippines, and a third of Thailand’s economic output.