Printing technology has evolved significantly, with modern techniques such as silk screening, gravure printing, typo, laser, offset, flexo, and digital printing. For thousands of years during the feudal era, the main printing technology used woodblock printing, and ink was made from traditional materials. Vietnam still preserves ancient wooden printing blocks, known as “mộc bản,” which are considered national treasures.

THE TREASURE OF ANCIENT PRINTING BLOCKS

Vinh Nghiem Pagoda (Duc La Pagoda) in Tri Yen commune, Yen Dung district, Bac Giang province, is a renowned ancient temple with a special place in the history and culture of Vietnamese Buddhism. The book “Tam To Thuc Luc” mentions that on the first day of the first lunar month of 1308, King Tran Nhan Tong (also known as Supreme Patriarch Giac Hoang Tran Nhan Tong) sent Monk Phap Loa to become the abbot of Bao An Pagoda in Super Genre. In April, he went to Vinh Nghiem Pagoda in Lang Giang to lecture on “Truyen Deng Luc” and appointed Phap Loa as the abbot, with Quoc Su Dao Nhat lecturing on Phap Loa’s dharma for the assembly. In September 1313, Phap Loa, following the royal order, came to reside at Vinh Nghiem Pagoda, establishing the headquarters of the Central Buddhist Church of Dai Viet to develop the country’s religion.

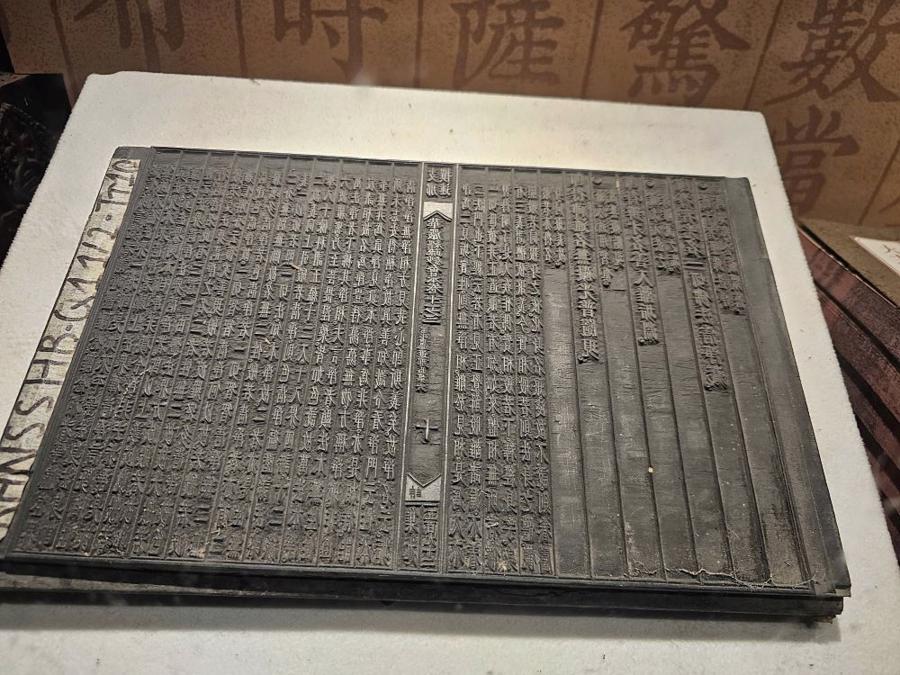

Vinh Nghiem Pagoda currently houses 3,050 wooden printing blocks in Chinese, Nom, and Sanskrit, dating from the 16th century to the early 20th century. The content of the blocks includes scriptures and books compiled by the three patriarchs of Truc Lam: Tran Nhan Tong, Phap Loa, and Huyen Quang, as well as their successive sects.

In addition to religious texts such as sutras and precepts, the collection of wooden printing blocks at Vinh Nghiem Pagoda also contains literary works and valuable documents on aesthetics and medicine. The material used for carving these blocks is wood from the sterculia tree. Some of the trees were grown within the pagoda’s premises. In the past, there were dozens of sterculia trees in the pagoda that were cut down to make the printing blocks. Today, two sterculia tree stumps remain, believed to have been used for the same purpose.

The collection of printing blocks at Vinh Nghiem Pagoda has been preserved using traditional methods. Due to repeated printing, the blocks have turned a glossy black, with a thick layer of ink coating their surface. This ink layer, absorbed into the wood, acts as a water-resistant and anti-mold agent, protecting the blocks from warping, insects, and moisture. Despite their age, the printing blocks at Vinh Nghiem Pagoda remain straight and the carved characters are still exquisite.

Recognizing their exceptional historical and scientific value, UNESCO inscribed the collection of 3,050 printing blocks at Vinh Nghiem Pagoda on the Memory of the World Register for Asia and the Pacific region on May 16, 2012.

Bo Da Temple, located at the foot of Bo Da Mountain in Tien Son commune, Viet Yen district, Bac Giang province, is the birthplace of the Lam Te Zen sect during the Le Trung Hung period. The Most Venerable Thich Tuc Vinh, abbot of Bo Da Pagoda, shared that the temple houses over 2,000 printing blocks made of sterculia wood, carved from the 18th century to the 20th century. The oldest blocks date back to 1740, during the reign of King Le Kinh Hung.

The printing blocks at Bo Da Pagoda are arranged on ten wooden shelves, with each shelf holding nearly 200 blocks. Most of the blocks measure 45 cm in length, 22 cm in width, and 2.5 cm in thickness, while some larger blocks are 60 cm long, 25 cm wide, and 2.5 cm thick. There are also very large blocks measuring 150 cm in length, 30 cm in width, and 2.5 cm in thickness. The blocks are inscribed in Chinese, Nom, and Sanskrit characters.

On these blocks, the ancestors left their mark through content, lines, intricate and exquisite patterns, and images. These patterns and images enhance the aesthetic value and create a harmonious blend of text and art. Despite the passage of nearly three centuries, the carvings and characters on the sterculia wood blocks remain sharp and unaffected by termites.

According to researchers, the valuable printing blocks at Bo Da Pagoda provide insights into ancient printing techniques and hold significance in assessing the independence of thought and culture in the nation. They also contribute to the study of linguistic development and the Vietnamese writing system, reflecting the transition from predominantly using Chinese characters to valuing and actively employing Nom characters.

In 2017, the collection of printing blocks at Bo Da Pagoda was recognized by the Worldkings World Records Union and the Asia Book of Records as the oldest collection of Buddhist sutra printing blocks made of sterculia wood in the world. In 2018, the Prime Minister’s Decision officially acknowledged these printing blocks as “National Treasures.”

MANY PRINTING BLOCK HERITAGE SITES HAVE BEEN CONVERTED INTO FIREWOOD

The Most Venerable Thich Tien Dat, Deputy Director of the Institute of Buddhist Studies in Vietnam, Hanoi, and Director of the Buddhist Documents Center, shared that “woodblock printing” refers to texts in Chinese and Nom characters engraved in reverse on wood, which are then printed to create books. Since the country’s independence in 1945, Chinese characters are no longer the national language, leading to the loss of Chinese-related documents and knowledge. As a result, the collection of ancient books and printing blocks has significantly diminished.

“I have visited temples where I once saw large cabinets containing ancient sutras and books, only to find them missing on subsequent visits. When asked, I was told that termites had destroyed them,” shared the Most Venerable Thich Tien Dat. “At the beginning of the 20th century, the French in Vietnam recorded several hundred thousand ancient printing blocks. In reality, according to our ongoing nationwide survey, there are only over 30,000 printing blocks remaining. Sadly, in some temples without monks or nuns, locals chopped up the printing blocks for firewood.”

The Most Venerable Thich Tien Dat added that in ancient China and Japan, the state or organizations were primarily responsible for printing, with centralized printing facilities. In contrast, Korean and Japanese temples were officially designated to engrave printing blocks for sutras.

However, in Vietnam, printing, including Buddhist sutras and books on literature, history, and medicine, was carried out by the temples themselves. In addition to Buddhist scriptures, the “Nho, y, ly, so” categories were prevalent in ancient temples, covering books on medicine and Eastern medicine in particular. Many funeral and wedding texts also reflected the influence and interplay between Buddhist culture and folk culture. Buddhism also developed ritual books for the deceased.

Analyzing the research on ancient printing techniques, the Most Venerable Thich Tien Dat shared that the primary wood used for engraving in ancient Vietnam was sterculia wood. This wood is resistant to warping and has the flexibility to withstand small character engravings without breaking. Additionally, it is termite-resistant and long-lasting. Importantly, sterculia wood absorbs water, making it suitable for printing. Its fine grain structure produces crisp and even characters without blurring. Before engraving, the sterculia wood is thoroughly boiled and chemically treated to prevent expansion and contraction, ensuring its adaptability to the harsh northern climate.

A RIGOROUS PRINTING PROCESS

According to the Most Venerable Thich Tien Dat, when printing books, it is essential not to use Chinese ink or oil-based inks. These inks tend to adhere to the engraved wooden characters after multiple printings, causing the characters to thicken and become unusable. Attempting to remove the ink would result in distorting the engraved lines.

“The ink used in ancient times was made by soaking bamboo charcoal in water for 3-5 years, grinding it into a fine powder, filtering it, and then mixing it with glutinous rice powder. This ink was prepared fresh daily and could not be stored for the next day,” emphasized the Most Venerable Thich Tien Dat. “The brush used to apply the ink to the wooden blocks had to be made from pine needles. With this ancient printing technique, the characters were incredibly sharp, and the books could last for hundreds of years without the ink fading. Even if the pages tore, the characters remained intact.”

“During the engraving process, there was strict supervision and multiple checks. After completing the engraving, a test print was made, and further inspections were conducted to identify any errors. If a mistake was found, the incorrect character would be cut out and replaced with a new one. Naturally, the engraver who made the mistake would be penalized.”

The Most Venerable Thich Tien Dat, Deputy Director of the Institute of Buddhist Studies in Vietnam, Hanoi.

Regarding censorship in the engraving process, the Most Venerable Thich Tien Dat shared that there were clear regulations in place. Only those with beautiful and consistent calligraphy were allowed to engrave characters onto the wooden blocks.

Upon completing a book’s printing, a dharma assembly was often held, inviting eminent monks and court officials to attend. The newly printed book would be read aloud for the assembly to hear, allowing for the detection of any content-related errors. Only after confirming the absence of mistakes would the book be published…

The full content of this article is available in the Vietnamese version of the Vietnam Economic Times, No. 3-20245, published on January 20, 2025. Please click the following link to read the full story: https://postenp.phaha.vn/chi-tiet-toa-soan/tap-chi-kinh-te-viet-nama>.

![[On the Hot Seat] Haval Vietnam: Missteps and All](https://xe.today/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/quote-temp-1-100x70.jpg)