In June 1999, what started as a sandwich stall on the street to support nine homeless children has now become a famous restaurant and a “must-go” destination for many domestic and international tourists. Located on the bustling Van Mieu Street, just a stone’s throw away from Vietnam’s first university, KOTO has also hosted important guests such as President Bill Clinton during his first visit to Vietnam, as well as ambassadors from Australia, Switzerland, and Denmark. It has also been a “home and school” to more than 1,700 students who are young people with special circumstances.

KOTO’s founder, Mr. Jimmy Pham, after busy days of fundraising and managing general affairs, always returns to his simple joy: cooking a meal to share with the students, whom he affectionately calls “my younger siblings.” After graduating, 100% of KOTO students have found stable jobs in 4- and 5-star hotels and restaurants; 67% of them are in managerial and executive positions at prominent brands; and many alumni have been very successful in their chosen fields. In a letter to the alumni on the 20th anniversary of KOTO’s founding, Jimmy Pham simply wrote, “Come home, my dear siblings!”

“A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.” Today, KOTO has become a well-known brand. But what were those first steps like, and what challenges did they entail? Can you share some memories from the early days of KOTO’s establishment?

In 1999, I established KOTO with a social enterprise model to support young people with special circumstances. At that time, the concept of a social enterprise was very new and novel. This novelty led to quite a few difficulties. I was suspected of being a “wolf in sheep’s clothing,” of being a fraud, because society had a simple view: either you do charity – which means giving money, or you do business – which means making money, but there was no such thing as a social enterprise. The field I chose was quite sensitive: tourism and services, and the target group was also very specific: street children, homeless and disadvantaged youth, some of whom had not even completed primary school.

When I took these children into the facility, I taught them culinary skills. At that time, people thought that anyone could cook, that it was something you didn’t need to learn; or if you did learn, it would only take 3 to 6 months to master. But my school taught them for 2 years. People criticized me for being “too free, too rich,” and they always said I would fail soon. So, in addition to financial difficulties, I also had to face societal prejudices. And the most challenging part was changing those prejudices. Throughout the journey of almost 25 years, we have always tried and endeavored to help people understand that at KOTO, we don’t do charity; we invest in people, help them develop, and enable them to become contributing members of society.

Twenty-five years is a journey filled with ‘thorns and bumps.’ Have you ever thought of giving up during this challenging period?

I think about it every day. Every morning when I wake up, I ask myself if I can do it, as my ambition is too big! But when I step into the restaurant and am greeted by the students with their hopeful smiles and shining eyes, I feel motivated to keep going. In the beginning, I helped 150 children. If you think of them as just numbers, it’s quite limited, but if you think of them as 150 lives that will have the chance to change and find their light, it’s miraculous and a source of strength for me to strive for.

I remember during the Covid pandemic, our model, which relied heavily on tourism, was almost wiped out: the restaurant couldn’t operate, there was no income, and we couldn’t even maintain the children’s accommodation. In the scorching 45-degree weather, we had to move with nearly 100 people. The children had nowhere to go, and I couldn’t bear to put them out on the street. Fortunately, I received help from friends and former students. One-third of our operating expenses at that time came from the support and contributions of our alumni.

The career I had built for over 20 years was almost ruined and lost. But it was a lesson for me to realize what I needed to do to protect what was precious, to protect my assets – my dear siblings. From then on, I rebuilt KOTO in a more robust and logical way. Looking back now, I am grateful for the difficulties and even the people who doubted and ridiculed me because they taught me to grow and try harder. I really like a saying that social entrepreneurs need three qualities: extraordinary, irrational, and daring to go against public opinion.

During the two years at KOTO, what do the students learn? Is it just cooking, or is there more to it?

I studied hotel management and worked in the tourism industry. I also realized that tourism is a very promising industry in Vietnam, so I wanted to teach the children a trade. At KOTO, they not only learn F&B skills but also life skills, culture, English, and IT… Their entry level at KOTO is quite low due to their special circumstances, so they don’t have much education and are quite shy. Therefore, in addition to vocational training, we also want to build their confidence, help them feel loved, and empower them to decide their future.

With the 2-year training program at KOTO, students must ensure a balance between 400 hours of theory and 400 hours of practice. After 2 years of study, they will receive a vocational certificate from Box Hill Institute, Australia. We also collaborate with Apollo English Center (British Council) to teach English communication and hospitality-specific language skills. Thanks to this, three months before graduation, students can be invited to work at many 5-star hotels with a starting salary of $400-600 USD/month (approximately 10-15 million VND/month).

In KOTO’s mission, you mentioned “empowerment.” What does “empowerment” mean in this context?

As you know, the children at KOTO come from difficult backgrounds; some are street children, some shine shoes for a living, and some are orphans… If we think of it as charity, which means giving them food and clothing, it won’t be sustainable. I want to help them more. I believe that everyone has the right to be loved, educated, and to decide their destiny, and no one wants to be pitied, even if they are in difficult circumstances. So, we empower them by giving them the rights they deserve so that no one is left behind.

Empowerment here means investing in the people we are helping, providing them with knowledge, skills, and a trade to help them earn a living. This is a sustainable and long-term solution. Our journey has proven that empowerment is the right direction. Today, 100% of our graduates have stable jobs at 4- and 5-star hotels nationwide, including renowned names such as Hilton Hanoi, Jaspas Saigon, Sheraton, and Sofitel Metropole… Among them, 62% hold managerial and executive positions. Many have started their own businesses, taken care of their families, and come back to support the “common home” of KOTO.

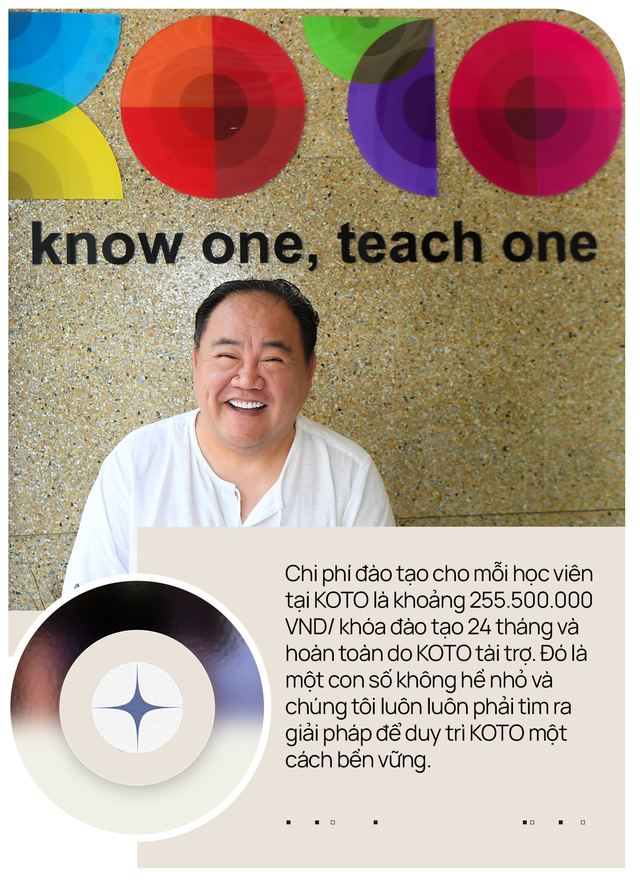

Is there a difference between running a social enterprise and a traditional business?

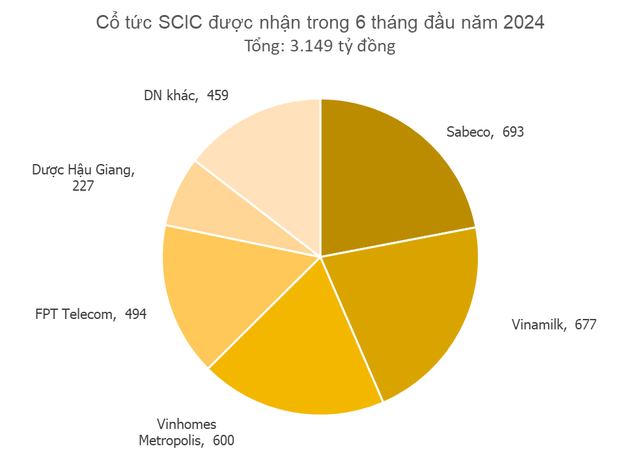

It’s completely different. While a traditional business enjoys the profits from its operations, a social enterprise uses those profits for social purposes. In other words, it is a non-profit organization. However, a social enterprise is still a business, and financial issues are a burden that we always have to deal with and find solutions to achieve growth. The training cost for each student at KOTO is approximately 255,500,000 VND/24-month training course, and KOTO fully sponsors this amount. It’s a considerable number, and we always have to find solutions to sustain KOTO’s operations. Seventy percent of the organization’s operating costs come from the restaurant’s profits.

Another difference is that we have to excel in both business and education, including taking care of the students’ mental and physical health. The students at KOTO are between 18 and 24 years old. This is the age when they are at a crossroads: they can either become good, contributing members of society or become a burden and fall into vices… At this age, if they don’t have a trade, they will be very shy and insecure and may go astray.

Are there any specific challenges in the governance of a social enterprise?

One mistake that social enterprises make is thinking that because they have a social purpose, people should help them. We don’t think that way. KOTO was established with the primary purpose of providing a place for students to practice what they have learned. Over the past 25 years, we have affirmed our position and become well-known, not by advertising ourselves as a charitable organization or promoting the fact that we help disadvantaged youth… but because customers know us for our good service, delicious food, competitive prices, and beautiful location.

For a social enterprise to succeed, it needs to change its mindset and build a solid business model, including agile sales and marketing departments… It’s like the story of giving a man a fish versus teaching him how to fish. I don’t want to give the children a fish; I want to give them a fishing rod so they can fish for themselves. And it’s the same for us; we can’t rely on support; we have to generate our own income. Most projects will stop when the funding runs out, but KOTO is a big family with many children. All these children need to be cared for, fed, and educated until they are ready to go out and contribute to society. Therefore, KOTO will not stop just because funding runs out.

KOTO is a family, but at the same time, it is also a business that needs a clear structure and professional operating procedures. Are these two aspects contradictory?

I try to create a model that is as close to reality as possible so that the students can practice what they have learned because that’s what the real world is like. They will not be given any special treatment or concessions because of their circumstances. When they step into the restaurant, they are trained staff, and they need to work professionally and seriously.

But we are also flexible. I understand that love is something that needs to be shared and spread. The students must feel loved and cared for to be able to do the same for others. They are a specific group, so the first thing they need to learn is how to greet, how to speak, and how to communicate… Vietnamese culture has a beautiful and valuable tradition, and we want them to understand and empathize with these values to grow up to be good people.

You mentioned that during the most challenging times, like the Covid pandemic, you realized that you needed to take action to protect your “most significant asset – your siblings.” So, is it safe to say that people are at the core of KOTO?

Absolutely. My target group is homeless, disadvantaged, and special circumstances children… People think that they are rebellious, difficult to teach and discipline… but with KOTO’s guidance, they have become contributing, polite, and knowledgeable individuals… I am proud of that.

I have an incredible team that always accompanies me and believes in our core values. Ninety-five percent of the restaurant’s operations are contributed to and run with the help of our alumni. Many of them are senior managers in famous hotel and travel brands and have come back to support us. Therefore, the project’s value doesn’t just stop at the 2-year training but continues to spread. The alumni always accompany and support us, forming a large family of love and solidarity.

After leaving KOTO, the alumni have worked in many famous hotels and restaurants nationwide, and some are working or studying abroad. On the 20th anniversary of KOTO’s founding, I wrote a letter to them, saying, “KOTO used to be