While the concept of tariffs is not new, the return to a “reciprocal tax” model under Donald Trump has prompted many countries to re-evaluate their economic structures and choose their development paths. In the global supply chain, ASEAN was once considered an alternative to China. However, this substitution is only sustainable if it is accompanied by the ability to withstand policy shocks. The issue is not about the percentage of tariffs imposed but about which countries are affected in terms of export structure, capital flow, and macroeconomic status.

As the US uses tariffs to reshape global trade relations, all countries must answer the following questions: “What do I lose if I am subjected to high tariffs? And more importantly, what can I change to avoid being left out of the game?” Analyzing the tariff resilience of ASEAN countries provides insight into the clear differentiation in thinking, actions, and policy adaptability among countries in the same region.

Assessing the impact of tariffs on ASEAN countries

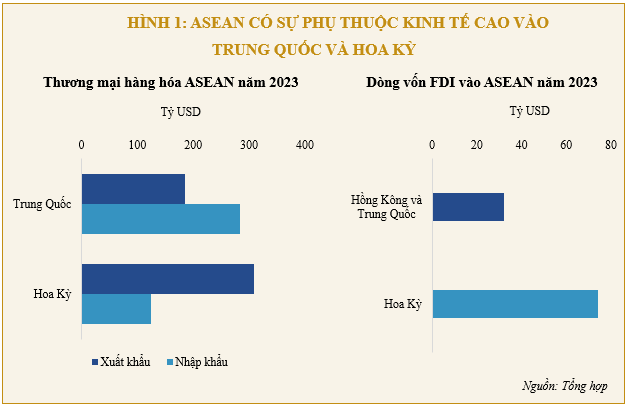

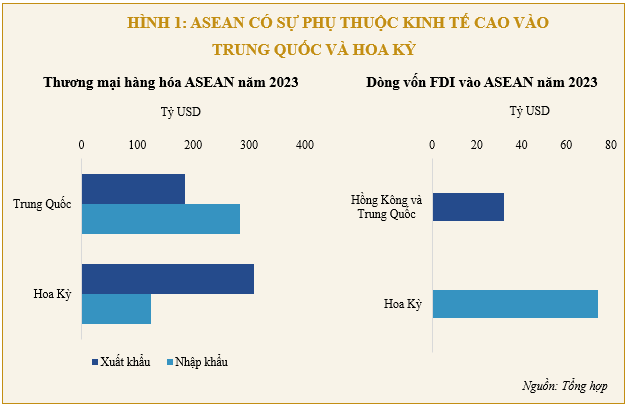

The common characteristic of the ASEAN economic bloc is its high dependence on the US market for exports and on China for imports. It is estimated that ASEAN’s trade surplus with the US could reach 200 billion USD, while the trade deficit with China is about 100 billion USD in 2023. In terms of FDI, ASEAN countries received a record investment of 74 billion USD from US investors in 2023. This position has provided a significant growth impetus for the ASEAN region in the past decades, but it is also a significant disadvantage for the entire region in this tariff war.

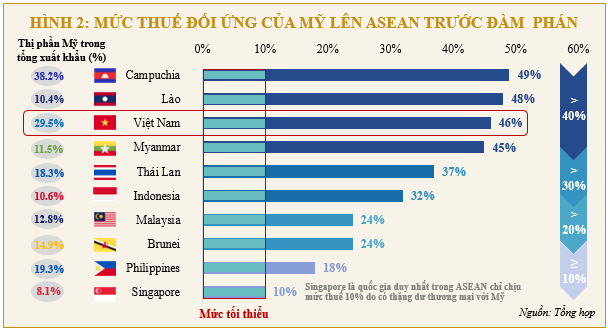

Vietnam is at the highest risk, with 30% of its export turnover dependent on the US, mainly in high-value-added industries such as textiles, electronics, and wood products. Due to the large bilateral surplus, Vietnam faces the risk of being subjected to the highest tariff rates, even after negotiations. With these tariffs, export profit margins could be wiped out, leading to a contraction in FDI and order diversion.

Compared to Vietnam, countries in the region, such as Thailand and Malaysia, have higher localization rates in export production. This is evident in the dominant role of local enterprises in key industries. In Thailand, the top three export industries to the US in 2024 were computers and components (6.51 billion USD, accounting for 12.2% of total exports to the US), telephones and components (5.71 billion USD, 10.7%), and rubber products (4.4 billion USD, 8.3%). It is noteworthy that these export industries are closely linked to Thailand’s long-standing foundational industries, where local enterprises not only participate in assembly but also master core technologies, supply chains, and international market shares. In particular, the automotive industry, nicknamed “Detroit of Southeast Asia,” is a typical example of complete production capability and high localization.

Meanwhile, Malaysia has developed a well-established high-tech industrial model, with integrated circuits reaching 16.2 billion USD, accounting for 30.8% of total exports to the US. This is followed by semiconductor devices and telephones and components. Malaysia has built a robust domestic enterprise ecosystem capable of production and establishing bilateral trade relations with the US. Notably, most of the imported components from the US are used for re-export to the same market. This is a significant difference from Vietnam, which still relies heavily on raw material imports from China and South Korea.

Additionally, Malaysia and Thailand have lower export ratios to the US compared to Vietnam, at 14% and 11.9%, respectively, but they still face pre-negotiation tariff rates of 24% and 37%. The difference lies in the fact that Malaysia, despite the tariffs, is considered a reliable alternative destination due to its neutral stance and better supply chain autonomy compared to other regional countries. Thailand is subjected to high tariffs but lacks the policy impetus to react swiftly and find sufficiently large alternative export markets.

Indonesia and the Philippines are not overly dependent on the US, with export ratios of 9.3% and 7.5%, respectively, but they still face tariffs of over 20%, indicating that political structure and bilateral relations also influence US tariff policies. Singapore, despite only exporting 8.2% to the US, faces a 19% tariff due to its role as the region’s financial, logistics, and technology hub.

Trade, tariffs, and exports have painted a clear picture of differentiation. However, to understand resilience better, we need to delve deeper into the macroeconomic layer, where the US dollar plays a stabilizing role and underpins all international capital flows. The ability to maintain USD flows is crucial for maintaining macroeconomic stability in the context of volatile international capital flows. In this regard, Vietnam uses USD earnings from exports to balance exchange rates and increase foreign reserves. A decline in this foreign currency source could lead to a double deficit in ASEAN countries.

The Philippines is even more dependent on the USD through remittances and the BPO outsourcing industry, accounting for more than 15% of GDP. This makes the economy vulnerable if the US tightens immigration policies or reduces outsourcing services. In contrast, Malaysia and Thailand maintain more diverse USD sources from investment, exports, and tourism. Singapore, as the region’s financial center, has strong defensive capabilities but is indirectly vulnerable if global capital flows shift away from Asia.

In addition to exchange rates and foreign reserves, a less noticed but crucial variable is the supply chain, which is the backbone of maintaining export capacity when faced with “output blockage.” From this perspective, ASEAN countries once again demonstrate significant differences in sensitivity and flexibility. Vietnam and Indonesia’s excessive dependence on imported inputs is a significant weakness in industries such as electronics, where the proportion of components imported from China and South Korea reaches 70-80%. Any disruption in supply would hinder export capacity, exacerbating the risk of tariff imposition.

Malaysia stands out for its diverse auxiliary industries, capable of adjusting flexibly to meet partner requirements. Thailand has a stable supply chain but is slow to innovate, focusing too heavily on traditional automotive and electronics industries. The Philippines has an insufficiently deep production chain, making it challenging to integrate into the regional network. Singapore, as a transit hub, is also vulnerable to changes in trade flows.

The above analyses highlight the resilience of each country in terms of fundamental factors such as trade, macroeconomic stability, and supply chain capabilities. However, the critical aspect is not just the level of vulnerability but how they respond to tariff shocks. A country may suffer significant damage but still escape if it has the right strategy, reacts swiftly, and has far-reaching policies.

Policy responses and adaptability of the six ASEAN countries

Initial policy responses shape positions. However, to go further in the new game, the ability to reposition in the supply chain and, more importantly, in the new economic order, is crucial. Nevertheless, strategy choices also depend on each country’s potential and long-term economic development orientation.

Malaysia is a model of proactiveness. Immediately after signals from the US, the country established a specialized task force, promoted bilateral and multilateral negotiations, and skillfully utilized its neutral stance to attract diverted capital. Meanwhile, Singapore, with its long-term vision, has begun transforming from physical logistics to data centers and digital finance. Although Singapore leads in technology and innovation, it must race against time to maintain its dominant role as other destinations begin to receive more favor from the US.

Thailand maintains stability, but this stability has become a weakness when rapid transformation is needed. The country needs to break free from the traditional orbit of the automotive and electronics industries to avoid being left out of the game due to US tariff impacts. Meanwhile, the Philippines is promoting the digital transformation of the BPO industry but faces challenges in training human resources and investing in technology to support the rapid transformation. This situation exposes them to a clear risk: losing the significant USD inflows from remittances and outsourcing without a sufficiently strong alternative economic sector. Indonesia has a large scale but is not yet ready to replace its role as a manufacturing hub. Although the country is investing heavily in electricity, nickel, and electric vehicle batteries, the lack of infrastructure and connectivity policies will isolate it in the regional supply chain landscape.

If ASEAN is to be considered an alternative to China, we must determine which country is most ready to embrace this wave of relocation. Looking at the overall picture, it becomes apparent that Vietnam needs to be much more determined. We lack a clear strategy to redefine our value chain or negotiate bilaterally effectively. While Vietnam attracts significant FDI, we need to increase localization by developing our weak raw material and auxiliary industries. Additionally, our export markets need to be more diversified. Vietnam’s most significant risk is being “stuck in the middle,” dependent on the US and lacking the internal resources to replace imports from China. Without diversifying markets and improving the quality of our domestic supply chain, Vietnam could lose its competitive advantage in the next decade.

While there are opportunities for repositioning, the reality is that inaction will lead to passivity, and strategic risks will not merely be a scenario but an existing prospect. This risk takes on different shades in each country but shares a common thread: losing long-term positioning. US tariff policies are a strategic test, examining each country’s ability to adapt, react, and reshape its role in the global supply chain. Malaysia and Singapore have clear directions and can maintain or enhance their positions. Vietnam, the Philippines, Indonesia, and Thailand need to act faster to withstand tariffs and safeguard their countries’ competitive positions in the long term.

Lê Hoài Ân, CFA – Võ Nhật Anh, UEL

– 12:00 26/05/2025

“Premier Pham Minh Chinh Named Outstanding ASEAN Leader 2025”

On May 25, in Kuala Lumpur, as part of his official visit to Malaysia and attendance at the 46th ASEAN Summit, Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh participated in the ASEAN Leadership and Partnership Forum. At this event, the Asia-Pacific Strategic Research Institute (KSI) honored him as the Outstanding ASEAN Leader of the Year 2025 – a recognition of Vietnam’s significant contributions to the region’s development process.

“GHTK’s Participation at Viet Cargo Expo 2025”

From May 21 to 23, 2025, Giao Hàng Tiết Kiệm (GHTK) participated in the Viet Cargo Expo 2025 (VCE), Vietnam’s premier exhibition for logistics and cargo professionals. The event was held at the WTC Expo Convention and Exhibition Center in Binh Duong, bringing together industry leaders and experts to showcase the latest innovations and solutions in the logistics and cargo sector.

Activating ‘Priority Mode’: A Proposal for Expedited Customs Clearance for High-Tech Goods

“Businesses involved in the manufacturing of integrated circuits, electronic components, and high-tech equipment are now offered a streamlined process for customs clearance. Those who meet the specified criteria will be granted priority status, benefiting from expedited procedures, faster clearance, reduced physical inspections, and pre-arrival customs processing. This efficient system ensures a seamless experience for qualified businesses, enhancing their competitiveness in the dynamic tech industry.”

“US Tariffs Threaten FDI Appeal: Is Industrial Real Estate at Risk?”

The recent announcement of tariffs by the US, imposing up to 46% on exports from Vietnam, presents a significant challenge for various economic sectors, particularly industrial real estate. This industry has traditionally thrived on foreign direct investment and the demand for expanded production capabilities.