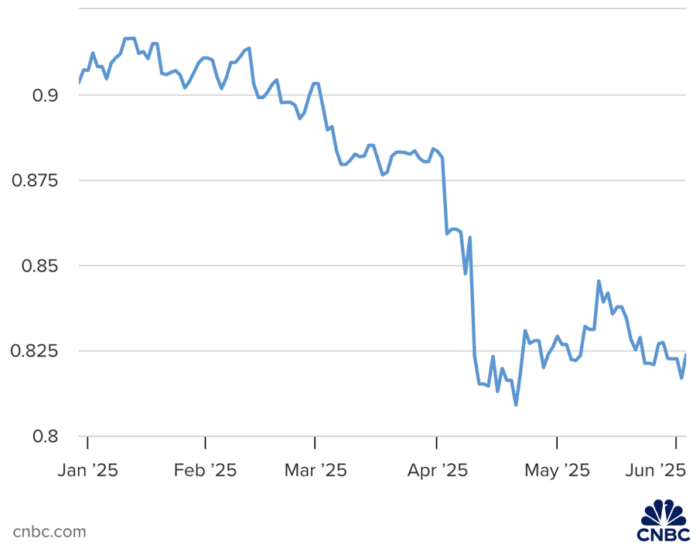

President Trump’s tariff policies have caused global financial markets to wobble in recent weeks, prompting investors to snap up assets deemed safe. Among them is the Swiss franc – a haven in times of heightened macro-economic and geopolitical uncertainty.

So far this year, the Swiss franc has appreciated by around 10% against the US dollar. However, according to CNBC, this is not good news for the country’s policymakers but a significant challenge. A strong domestic currency increases deflationary pressure on the Swiss economy as imports – which play a crucial role in the country – become cheaper when the franc rises.

While a stronger currency is usually welcomed by many countries as it helps curb stubborn inflation, Switzerland faces the opposite problem. While developed economies like the US and UK struggle to bring inflation down to their central bank’s target of 2%, Switzerland grapples with a swift decline in prices.

Inflation data released this week showed that Switzerland slipped into deflation in May, with consumer prices falling 0.1% from a year earlier. Import prices dropped sharply, falling 2.4% year-on-year after stagnating in April.

ING economist Charlotte de Montpellier highlighted the role of the strong currency in Switzerland’s inflation dynamics. “The latest drop in Swiss inflation is mainly due to external factors. A strong franc has caused import prices to fall sharply. Given that imports make up 23% of the CPI basket, this has a significant impact on overall Swiss inflation,” Montpellier told CNBC.

The May inflation data marked the first time Switzerland experienced deflation since the Covid-19 pandemic. This situation could force the Swiss National Bank (SNB) to resort to two key tools it has used in the past to tackle what Montpellier calls a “persistent headache” for the central bank: negative interest rates and currency intervention.

NEGATIVE INTEREST RATES

The SNB ended seven years of negative interest rates in 2022, a policy unpopular with depositors and lenders in Switzerland as it effectively taxes savers and squeezes bank profit margins.

At its most recent monetary policy meeting in March, the SNB cut its benchmark interest rate by 0.25 percentage points to 0.25%.

Following the release of the latest inflation data, the SNB is expected to “try to counter the franc’s appreciation with the tools at its disposal,” Montpellier said.

“Based on the current data, a return to negative rates before the end of the year is becoming increasingly likely. Our main scenario is for the SNB to cut rates by 0.25 percentage points twice between now and September, bringing the policy rate back to -0.25%. While the SNB wants to avoid cutting rates too sharply, the possibility of a 0.5 percentage point cut in June cannot be ruled out,” she added.

ING forecasts the SNB will stop cutting rates at -0.25%, and Montpellier said that if the franc continues to strengthen, the central bank will have no choice but to push rates further into negative territory.

INSEAD finance professor Lily Fang told CNBC that the current situation could push Switzerland back into negative interest rate territory – an option that SNB Chairman Martin Schelgel has left open. “The Swiss authorities are clearly worried because they are a small, highly open economy dependent on international trade, and the US is Switzerland’s most important trading partner outside the European Union,” Fang remarked.

“Switzerland cut rates before the eurozone. I think it’s very likely that they will cut rates to zero and maybe even negative,” she added.

CURRENCY INTERVENTION

Another tool the SNB has used in the past to curb the Swiss franc’s strength is foreign exchange market intervention by selling francs and buying foreign currencies. However, with President Donald Trump back in the White House, this strategy may face political challenges.

In 2020, during Trump’s first term, the US Treasury labeled Switzerland a currency manipulator, accusing it of deliberately devaluing the franc against the dollar. The SNB denied these accusations.

This time, the Trump administration has indicated that currency intervention and non-tariff barriers are considered when determining retaliatory tariffs on a country-by-country basis. Washington has calculated that Switzerland – which eliminated all industrial tariffs last year – imposes a 61% tariff on US goods, and the US has responded with a 31% retaliatory tariff on Swiss goods.

While acknowledging that any currency intervention by the SNB could “provoke the US administration,” Montpellier argued that the central bank is likely to intervene in the markets in the coming months.

Alex King, founder of the personal finance platform Generation Money, argued that any direct purchases of foreign currencies by the SNB would “likely not sit well with the US administration.”

“When Switzerland was labeled a currency manipulator in 2020, the threat of tariffs wasn’t as prominent. Now, they are in a bind,” King told CNBC. “If the SNB intervenes directly in the foreign exchange market again, Switzerland could face higher US tariffs, and the negative impact of this could be worse than the short-term deflationary pressure.”

Last month, SNB Chairman Schlegel said Swiss officials had constructive exchanges with the US on the issue of currency intervention. “We have never influenced exchange rates to gain an advantage,” Schlegel said at an event in Lucerne.

“I’m not sure if Switzerland will immediately intervene in the foreign exchange market because the US could label them a currency manipulator again. I don’t think Switzerland wants that label again, so currency intervention will probably be their last resort,” Fang commented.