|

The high cost of borrowing prevents those in need from accessing capital to purchase social housing. Photo: H.P

|

Proposals for addressing the US housing crisis by presidential candidates Kamala Harris and Donald Trump highlight the deep ideological differences between political parties in addressing a shared challenge. Implementing effective solutions is no easy task, as demonstrated by the Chinese government’s well-intentioned but ultimately criticized approach of incentivizing local governments to purchase unsold commercial housing projects and convert them into social housing.

Nonetheless, it is imperative to recognize that social housing policies are a crucial component of a nation’s housing strategy. As aptly stated by a Bloomberg commentator, it is unreasonable to expect low-income individuals to compete in the same housing market as high-ranking executives of Australia’s largest listed companies. Social housing should be viewed as a safety net, providing affordable housing options separate from the free-market segment.

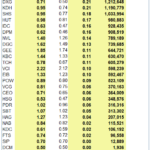

Vietnam’s social housing policies currently face three significant challenges: resources, supply, and demand. The $120 trillion credit package aimed at developing social and worker housing has encountered difficulties in disbursement due to the reliance on market forces rather than state resources. This has resulted in high borrowing costs, making it inaccessible to those it intends to serve.

|

Firstly, it is essential to establish social housing as a distinct public sector, operating independently from the private housing market. This separation ensures that the less fortunate are not forced to compete with real estate investors. |

The limited duration of preferential interest rates and the relatively small difference between subsidized and standard rates contribute to the challenges faced by borrowers and developers. Additionally, the lack of social housing projects and legal obstacles further hinder the effective utilization of the credit package.

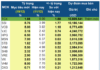

The third challenge lies in accurately identifying the target audience for social housing policies. While some localities report a lack of long-term housing demand among rural residents and industrial workers, others highlight the bureaucratic hurdles that make it difficult for those in need to access social housing. This misalignment between policy targets and actual needs underscores the necessity of reevaluating the approach to meet the demand for affordable rental housing rather than focusing solely on homeownership.

To address these challenges, it is imperative to revisit the fundamental issues. Social housing should be recognized as a public sector initiative, with government intervention setting the playing field. The success of this approach can be seen in countries like the UK and Singapore, although the latter has been more effective due to their smaller population and greater ability to allocate resources.

The high cost of borrowing prevents those in need from accessing capital to purchase social housing. Photo: H.P |

The crux of the social housing conundrum lies in the interplay between government intervention and market forces. While governments set the rules, the availability of resources and the ability to construct social housing units are pivotal. The UK’s experience demonstrates the limitations of government resources in meeting the housing needs of a large population, resulting in a reliance on private sector involvement, which inherently entails higher interest rates.

To make social housing accessible and affordable, governments must offer sufficiently attractive interest rates and extended preferential periods for both buyers and developers. This necessitates a substantial commitment of public funds, as relying solely on private sector solutions within their constrained parameters will not yield the desired outcomes. A more realistic approach would be to scale back the scope and ambition of social housing policies, focusing on smaller but more feasible commitments that address the core issues of interest rates, land costs, and regulatory flexibility to encourage private sector participation in providing affordable housing options for purchase and rent.

The second critical aspect is determining the appropriate beneficiaries of social housing. This has been a subject of debate among economists, as providing housing solely to the poorest segment of society can create unintended consequences. Excluding the middle class, who may not qualify as “poor,” forces them to compete with the ultra-wealthy in the private market. Attempts to regulate this market through capital gains taxes, transaction fees, and annual property taxes have proven ineffective in curbing skyrocketing housing prices. The ultra-rich often find legal ways to avoid or delay paying taxes, and their investment strategies may involve debt, business operations, and real estate exploitation, further complicating the equation. Moreover, some super-rich individuals purchase properties as a hobby, driving up prices in their desired neighborhoods and beyond. As a result, well-intended social housing policies can lead to the perverse incentive of individuals choosing to remain poor to qualify for social housing, which is detrimental to societal progress.

However, expanding the beneficiary pool stretches the already limited resources even further.

Vietnam’s social housing policies are hampered by overly ambitious goals that exceed available resources. A more realistic approach is needed, focusing on smaller but feasible commitments that address core issues.

To resolve the social housing dilemma, it is essential to reduce the scope and ambition of current policies and focus on increasing the supply of affordable housing for both purchase and rent. Instead of struggling to disburse massive credit packages that are misaligned with market forces, the government should provide incentives and relax regulations to encourage private sector involvement in providing affordable housing options. The growing demand for rental housing worldwide underscores the importance of including this option in Vietnam’s social housing strategy. By demonstrating the effectiveness and impact of these policies, the government can build trust and attract additional resources, including international concessional loans, to further expand and enhance social housing initiatives.

Identifying the right beneficiaries is a crucial yet complex task, as evidenced by instances of policy abuse in Hong Kong, Australia, and the UK, where social housing residents were found to own luxury cars and spend lavishly on vacations. Vietnam faces the additional challenge of ensuring proper implementation without overly complicated procedures that may deter eligible individuals from accessing social housing.

In conclusion, the social housing conundrum is not solely about banks, supply, or what we currently perceive it to be. It is a matter of government intervention and market forces, with the former setting the rules of the game. To achieve a balanced and effective solution, it is imperative to acknowledge the trade-offs and strive for the best possible equilibrium. Vietnam’s current social housing policies require adjustments, and a realistic assessment of available resources is necessary to formulate practical solutions.

Hồ Quốc Tuấn (Lecturer at the University of Bristol, UK)