The legendary investor, Warren Buffett, in 1965

|

Charlie Munger, Buffett’s right-hand man, once shared a profound investment philosophy: To be a good investor, you must fish where the fish are. But to be a great investor, you need to venture into uncharted waters.

This is the core message in Brett Gardner’s new book, “Buffett’s Early Investments,” which meticulously analyzes Warren Buffett’s first ten investments made between 1950 and 1966 when he was in his twenties and thirties.

Can modern investors apply Buffett’s early methods? In some ways, today’s environment is more favorable: information is easily accessible, transaction costs are negligible, and individual investors have certain advantages over institutions. However, today’s market is also much more competitive: it’s more efficient, bargains are almost extinct, and everyone wants to fish in the same spots.

To succeed like young Buffett, the key is to dare to be different, coupled with patience and courage. When asked about the lessons from the book, Buffett briefly replied that he would answer all questions about the author, Gardner, at Berkshire Hathaway’s annual shareholder meeting in 2025.

Gardner, an analyst at Discerene Group in Stamford, Connecticut, conducted a massive research project. He analyzed these ten companies solely based on the financial information Buffett had access to before deciding to invest in them.

For seven years, Gardner dedicated his Saturdays to this research before going all-in in 2023, delving into decades-old annual reports, analyst reports, Moody’s financial data manuals, and other rare documents.

Buffett’s first ten investments included: Marshall-Wells, Greif Bros. Cooperage, Cleveland Worsted Mills, Union Street Railway, Philadelphia and Reading Coal and Iron, British Columbia Power, American Express, Studebaker, Hochschild, Kohn & Co., and Walt Disney. While most of these companies are not well-known today, they were not prominent even back then. Gardner remarked about Marshall-Wells, “Any analyst could see it was a cheap stock.” Yet, very few paid attention to this Duluth, Minnesota-based hardware distributor. Similarly, Greif Bros., a barrel and container manufacturer, was sparsely traded on the Midwest Exchange.

Buffett didn’t merely study the available information. From an early age, even before he became famous, he actively went on-site to “bombard” management with insightful questions.

Today, due to the SEC’s Regulation Fair Disclosure in 2000, company management is prohibited from selectively sharing material non-public information with any investor without broad dissemination.

Buffett not only gleaned insights from management but also diligently studied all publicly available information. Patience was a key element in his approach. For instance, he once visited a Greif Bros. factory and spent hours chatting with workers to understand the barrel-making process.

In 1964, when American Express was embroiled in a scandal involving a subsidiary engaged in vegetable oil storage, Buffett and his partner traveled extensively, surveying countless restaurants, hotels, and retailers to confirm that the demand for Amex’s traveler’s checks and credit cards remained unaffected.

With Union Street Railway, due to the sparse trading of its stock, Buffett had to advertise in the local newspaper in New Bedford, Massachusetts, to invite shareholders to sell their stakes. It took him over two years to accumulate a significant amount.

Another critical factor in Buffett’s early success was his willingness to make substantial bets. Gardner observes, “Exceptional investment opportunities are rare, and Buffett took full advantage of them whenever he found them.”

In 1950, Buffett invested about a quarter of his net worth in Marshall-Wells. By 1951, more than half of his assets were in Geico. And in 1966, American Express accounted for nearly 40% of the partnership portfolio he managed.

Buffett’s rapid growth – from managing $500,000 in 1957 to $68 million a decade later – gave him a stronger voice. The ability to influence businesses through substantial shareholdings and board involvement is something most individual investors today cannot replicate.

However, modern investors have an advantage that young Buffett didn’t: the ability to invest a large portion of their portfolios in index funds that track the market, ensuring their investment performance doesn’t lag behind the overall market.

For the remaining 5-10% of their portfolios, investors can focus on a few companies that are still undervalued by the market. Gardner suggests looking for opportunities in niche markets where financial institutions have little interest and ETFs are not yet prevalent, such as community banks, spin-offs, micro-cap companies (with a market cap below $1 billion), or stocks removed from major indexes.

These strategies come with risks and require in-depth analysis, as Buffett did, and they may not be suitable for everyone. However, as Wall Street becomes increasingly obsessed with chasing the latest trends unconsciously, the lesson from young Buffett is clear: Profitable opportunities still exist for those willing to swim against the tide and venture into uncharted waters.

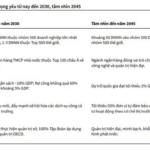

The Dragon Capital Expert: A Winning Strategy for Individual Investors

Investing consistently, maintaining discipline, and persevering in increasing investments, especially when the market undergoes significant corrections, to take advantage of buying opportunities at reasonable prices, is an effective strategy, according to experts at Dragon Capital, for individual investors to maximize their financial gains over time.