The Japanese yen has recently strengthened, emerging as a safe-haven investment amid volatile global financial markets due to unpredictable changes in US tariff policies.

However, according to a global asset manager, despite improved yen rate forecasts, Japan’s wealthiest individuals remain concerned about the economic outlook and are thus hesitant to bet on their currency’s appreciation.

In a conversation with Bloomberg, Daiju Aoki, regional investment manager at UBS SuMi Trust Wealth Management Co. in Tokyo, attributed this caution partly to the lingering trauma among Japan’s affluent households from the country’s stock market collapse in the early 1990s.

“Many wealthy clients are anxious about yen depreciation. They believe the yen could depreciate to 180–200 yen per USD due to a weak economic outlook and lack of investment in industrial production,” said Aoki. He added that his clients fear such a rate could emerge “in the next economic cycle,” despite short-term yen rate predictions being complicated by shifting US trade policies.

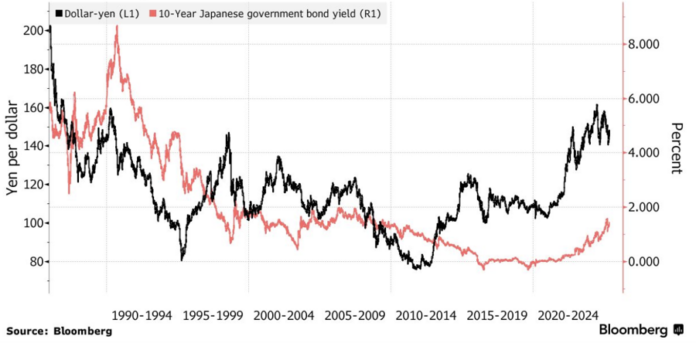

On May 15, the yen traded at over 146.2 yen per USD. At the end of April, the yen reached its highest level since September 2024, at around 142.9 yen per USD.

Recently, when the US and China reached a temporary trade agreement valid for 90 days, the yen began to weaken. On Monday, the yen depreciated by more than 2% against the USD, falling to nearly 150 yen per USD.

If the yen depreciates to the 180–200 yen per USD range, it would be a historically significant level. The last time the yen fell to 200 yen per USD was in 1986, a year after the Plaza Accord was signed to weaken the USD against major currencies, including the yen.

The yen’s appreciation back then posed a significant challenge to Japan’s export-dependent economy, leading the government to implement aggressive stimulus measures. However, this stimulus led to a stock market bubble, which burst around 1990, erasing the gains of the previous decades.

Currently, Japan’s major stock indexes have recovered to pre-bubble levels, and the yen has also depreciated to levels seen during that period. Nevertheless, the transformation of Japan’s economy in the decades since the bubble burst has become a source of anxiety for the country’s wealthy.

Once considered an economic superpower with unstoppable export prowess, ranging from electronics to automobiles, Japan now faces a declining and aging population, while much of the world’s innovation occurs in countries like the US and China.

Inflation in Japan, which has been low to non-existent for most of the time since the mid-1990s, is now accelerating—a contrast to the disinflation seen in most other developed economies. This rising inflation erodes the purchasing power of the vast cash holdings of Japan’s wealthy families.

“The Japanese rich are truly skeptical about the economy,” said Aoki, suggesting that without innovation and population growth, “the Japanese economy will lack supportive factors.”

This skepticism has led some of Aoki’s Japanese clients to increase their foreign asset holdings, while others seek the safety of gold. However, this anxious sentiment may imply that Japanese investors “feel holding cash is still preferable,” the asset manager noted.

Aoki opined that the yen would need to depreciate by over 20% to around 180 yen per USD to reduce his clients’ preference for cash holdings.

Last summer, the yen fell below 160 yen per USD for two weeks, but foreign investors and Japanese businesses were unimpressed. “The 160 yen level is not enough to attract significant foreign investment into Japan. Thus, the yen may continue to depreciate until Japanese companies repatriate their funds and foreign companies invest in developing infrastructure here,” Aoki concluded.