The private sector in Vietnam has come a long way since the early days of economic renovation. Once a vague and marginalized concept, it has now taken center stage as a key driver of economic growth, contributing not just directly but also through positive externalities that benefit the entire economy.

Against this backdrop, removing barriers and expanding the development space for the private sector is not just a choice but a strategic imperative.

Current Structure and Size of the Private Sector

According to Resolution No. 68 of the Politburo, Vietnam’s private sector comprises less than a million operating businesses (see Figure 1). This includes private enterprises, individual households, and collective economies. In reality, according to data from the central statistics agency (General Statistics Office), the private sector here is equivalent to the “non-state economy” in terms of statistics.

|

From 2010 to 2023, the non-state economy maintained a relatively stable proportion of added value in the gross domestic product (GDP), ranging from 49.7% to 50.4%. This modest increase hovering around 50% of GDP indicates that the sector’s contribution to GDP has remained largely unchanged over the past decade.

However, the average growth rate of added value in this sector reached 6.4%/year, outpacing the average GDP growth rate by approximately 0.4 percentage points. The foreign direct investment (FDI) sector exhibited even stronger growth, with an average added value increase of 7.87%/year, outperforming both the GDP and the non-state economy (surpassing the non-state economy by 1.82 percentage points).

The Rise of the Non-State Economy

Surprisingly, the FDI sector, long considered the primary growth engine, is gradually losing its prominence in the investment landscape. Its share of total social investment capital is on the decline.

|

The average growth rate of investment capital in the non-state economy during the 2010-2023 period reached 7.8%/year, almost double that of the FDI sector (4.1%). In an economy seeking internal impetus, this highlights the growing importance of domestic resources—a quiet but potentially decisive shift. |

In 2010, FDI investment accounted for about 21% of total social investment capital; by 2023, this figure had dropped to just 16%. Conversely, the non-state economy is emerging as a more significant driver, with its investment share surging from 44.6% in 2010 to 58% in 2023. The average growth rate of investment capital in the non-state economy during the 2010-2023 period reached 7.8%/year, almost double that of the FDI sector (4.1%). In an economy seeking internal impetus, this highlights the growing importance of domestic resources—a quiet but potentially decisive shift.

Investment Efficiency and Growth Constraints in the Private Sector

In the labor market, these two economic sectors are following contrasting trajectories. From 2010 to 2023, the labor force in the non-state economy remained almost stagnant, even experiencing a slight decrease of 0.07%/year. Meanwhile, the FDI sector recorded outstanding labor growth, averaging 8.94%/year.

GDP growth relies primarily on factors such as labor, capital, and total factor productivity (TFP). When one of these pillars weakens, sustainable growth becomes challenging.

Data from the General Statistics Office reveals that the non-state economy is slowing down, largely due to labor force constraints and low technology intensity, as evidenced by its weak total factor productivity (TFP). On the other hand, the FDI sector presents an intriguing paradox: while its share of total social investment capital is declining, its growth is accelerating. Its contribution to GDP is increasing (currently at 21%), and it is attracting more labor.

|

“Creating motivation” for the private sector is crucial, and “building trust” is the key to addressing the current challenges. For many years, an unstable, opaque, and unequal policy environment among different types of enterprises has eroded this trust. |

However, behind these impressive figures lies a concerning flip side—the outflow of money through ownership payments is increasing rapidly. From 2010 to 2023, while the average GDP growth rate at current prices reached approximately 10.6%/year, the net outward flow of money grew by 15.2%/year. Consequently, the ratio of gross national income (GNI) to GDP decreased from 97% in 2010 to 94% in 2023.

This raises a fundamental question for policymakers: instead of solely focusing on GDP, Vietnam needs to pay closer attention to indicators that genuinely reflect the economy’s health, such as GNI, net domestic income (NDI), and savings indicators for each institutional sector—state, enterprise, and household. While the General Statistics Office has published GNI data, indicators like NDI and savings are still not disclosed, making it challenging for policymakers to make informed decisions.

Trust Crisis and the Investment Conundrum

The number of private enterprises remains modest, and their economic contribution is not yet commensurate with their potential. This reflects not only limitations in scale but also qualitative constraints within Vietnam’s private sector.

According to the authors, “creating motivation” for the private sector is crucial, and “building trust” is the key to addressing the current challenges. For many years, an unstable, opaque, and unequal policy environment among different types of enterprises has eroded this trust. Many businesses are not afraid of market failure but are fearful of administrative procedures and tax-related errors, which could result in heavy penalties or even legal repercussions.

The decline in trust has led to concerning economic consequences. Instead of investing in production, technological innovation, or the digital economy, domestic capital is flowing into gold and real estate—safer havens but less efficient for the economy. When money remains just that and does not transform into productive capital, growth will stagnate and lack sustainability.

Capital Efficiency and Institutional Challenges

Another factor hindering growth is capital efficiency, or rather, the lack thereof. According to data from the General Statistics Office, Vietnam’s ICOR (Incremental Capital Output Ratio) —an index measuring the amount of capital required to generate a unit of growth—is deteriorating. In 2010, every 5.5 VND of investment created 1 VND of growth; by 2023, this ratio had worsened to 8 VND. In other words, the economy is “spending more to gain less.”

This not only reflects inefficiencies in resource allocation but also indicates hidden costs—from cumbersome administrative procedures leading to petty corruption—that are eroding the private sector’s investment incentives. And as reality shows, “petty corruption” is no small matter.

The Future of the Private Sector

So, how can the private sector truly break through?

From Removing Barriers to Building Trust

First, the state needs to focus on addressing the most pressing bottlenecks: reducing legal risks and administrative costs borne by businesses. This calls for concrete measures such as cutting unnecessary taxes and fees, eliminating wasteful hidden expenses that erode both profits and trust, and streamlining administrative procedures. An economy cannot function efficiently if there are too many “referees” on the field but too few “players” in the game.

Redefining the Business Environment for the Private Sector

Secondly, it is crucial to build a solid foundation of trust for the private sector, accompanied by a clear development roadmap. Trust does not arise spontaneously; it is the result of a cause-and-effect relationship between perception and action.

The four pivotal resolutions of the Politburo (Resolutions 57, 59, 66, and 68) that have been issued need to be swiftly institutionalized, widely communicated, and vigorously implemented to bring about substantive change. This process demands intellectual orientation, political will, and strong administrative capabilities—not just from the Party but also from the state administrative apparatus. And it takes time.

This is not merely technical reform but a journey toward building a new economic culture, aligned with a thorough private sector revolution. This journey necessitates perseverance, determination, patience, and resolve (“4K”); determination, vigor, commitment, and victory (“4Q”); and a spirit of confidence, self-reliance, fortitude, and pride (“4T”).

Only when the private sector is placed at the heart of innovation, treated equitably, rigorously protected, and appropriately honored, can trust be restored and elevated.

Maintaining Institutional Stability with a Focus on Technology and Integration

Thirdly, institutional reform must be sustained at a rapid pace and with substantial depth. Simultaneously, policy stability is indispensable for fostering long-term trust in the private sector.

Bui Trinh – Khuc Van Quy (FPT University & Hanoi National University)

The Stock Market’s Hidden Gems: Unveiling June’s Top Growth Stocks

The An Binh Securities (ABS) team believes that the market is currently presented with a medium-term growth opportunity, attributed to positive developments in trade negotiations and the government’s proactive efforts.

“Bà Rịa – Vũng Tàu: A Vision for Social Housing with 14,400 Homes”

The People’s Council of Ba Ria – Vung Tau Province has passed several important resolutions, including an ambitious goal for the development of over 14,400 social housing units by 2030. This significant target highlights the province’s commitment to addressing the housing needs of its residents and fostering a inclusive and thriving community.

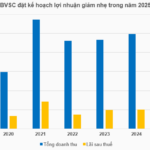

“BVS Aims for 195 Billion VND Profit, 8% Cash Dividend”

“BVSC, a leading securities company listed on the Hanoi Stock Exchange (HNX: BVS), is gearing up for its upcoming Annual General Meeting (AGM) scheduled for June 24, 2025, in Hanoi. The company aims to navigate through challenging market conditions with a proposed business plan targeting a net profit after tax of VND 195 billion, a 3% decrease compared to the previous year’s performance, amidst mounting cost pressures. The AGM agenda will also include considerations for an 8% cash dividend payout.”

The Average Vietnamese Income Script Achieves $28,370 Per Annum

According to experts, for Vietnam to join the ranks of high-income countries, there needs to be a period where its GDP growth reaches double digits (over 10%). This is an unprecedented threshold, an ambitious goal, yet not an impossible one. An ambitious scenario targets an 11-12% annual GDP growth rate during the period of 2025-2035, elevating the per capita income to $28,370 by 2045.