Public companies must adhere to strict rules when granting stock options to executives, including pricing the options at the company’s trading price on the day they are granted and quickly disclosing them.

Private companies planning to go public face similar requirements, but they have more time to price their stock options – because there is no public trading price – and more time to disclose them.

This difference has led dozens of private companies to offer their top managers low-priced options in the weeks leading up to their initial public offering (IPO). Interestingly, these individuals can often accurately predict the likely trading price of their stock, even before the public company’s rules on option pricing start to apply. This is the conclusion of a recent study by Sven Riethmueller, a professor at Yale Law School.

Riethmueller notes, “They only receive these equity grants last minute.” He calls this activity “11th-hour options discounting.”

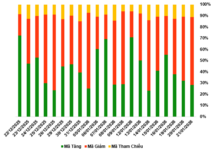

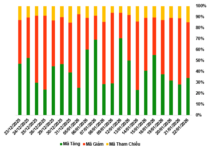

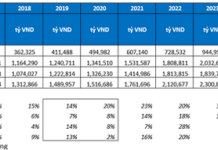

In his article, Riethmueller examined 121 biotech firms targeting IPOs from 2017 to 2021. He found that 74 options were granted to executives and employees within 90 days before the IPO, with an average discount of 48% compared to the IPO price.

Zoom, Beyond Meat, and Eventbrite are among the companies that also granted cheap stock options to their top executives and employees before their IPOs. Riethmueller consolidated his findings by thoroughly reviewing records and collecting non-public letters between the Securities and Exchange Commission and individual companies via the Freedom of Information Act.

Riethmueller found that by pricing the options at the last minute, companies virtually guarantee that the recipients will have an unexpected windfall on the first trading day. This lesser-known practice has become extremely popular with young companies often using cheap stock options as a way to attract C-suite executives. Companies often do not disclose the number of options allocated to individual executives until the night before the trading day, after the IPO price has been set.

Less than a month before the IPO, a small Boston-based biotech company called Galecto granted its top executives nearly a million stock options, each priced at $7.70.

Meanwhile, after the IPO, the stock price was set at $15 per share based on investor interest. So more than half of those deeply discounted options belonged to the company’s executives. When Galecto went public on October 28, 2020, the value of the executives’ stock options increased by $4 million.

By withholding information before the IPO, Galecto denied investors an accurate assessment of whether to buy its stock at $15. The information asymmetry also means investors did not fully assess Galecto’s compensation cost and whether the benefits to the top executives were aligned with their interests.

Galecto spokesperson Sandya von der Weid wrote in an email that the company could not grant options earlier because they had to wait for the completion of the private capital round before they could determine their valuation. She added, “These grants were proposed by an independent compensation adviser and approved by Galecto’s board of directors.”

Stock options, which allow holders to periodically purchase a company’s stock at a predetermined price within a few years, are a popular part of the compensation packages of senior executives.

Under regulations set by the SEC, public companies can only issue stock options at market price (or face severe tax consequences) and must disclose them to senior executives and other insiders within two days of granting them. By setting the exercise price of the options at market price, companies create an incentive for executives to increase stock value at the time the options are granted. A higher stock price is generally good for all investors.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, over 100 companies pegged option grant dates to the days their stocks were at their lowest levels; backdating these dates allowed executives to receive larger financial rewards.

These timing enabled their executives to immediately benefit as the stocks appreciated, making them “rich” overnight, at least on paper. The latter companies eventually became targets of lawsuits and huge fines by the SEC. Some executives were sentenced to prison.

The SEC also requires private companies to disclose clearly the stock options they grant to their top executives. However, unlike public companies, private companies only have to disclose those detailed information for their complete financial year before their IPO.

Erik Lie, a finance professor at the University of Iowa who discovered the timing issues with stock options, recently read Riethmueller’s article. “To me, it’s a simple game – you get the stock at a very cheap price.”

Source: NYTimes