According to forecasts by the General Statistics Office of Vietnam, the country’s transition from an aging population to an aged one is expected to take approximately 26 years, from 2011 to 2037. This is a very short period compared to highly developed countries, placing Vietnam among the fastest-aging populations in the world.

In terms of economic growth, Vietnam has experienced one of the longest growth periods globally (42 years), second only to the world record of 44 years held by the People’s Republic of China, including several years of double-digit growth.

Even during the COVID-19 pandemic, Vietnam was among the few countries to maintain positive growth. In 2023, Vietnam was also among the top countries with the highest GDP growth rates in the world. These growth rates are impressive, especially for a country with a low starting point, as higher and longer-lasting growth is a crucial solution.

NOT YET RICH AND SLOW TO GET RICH

In the past, there have been opinions against chasing high growth rates, especially in years with growth above 8%. Some even considered such growth rates as “overheating” the economy.

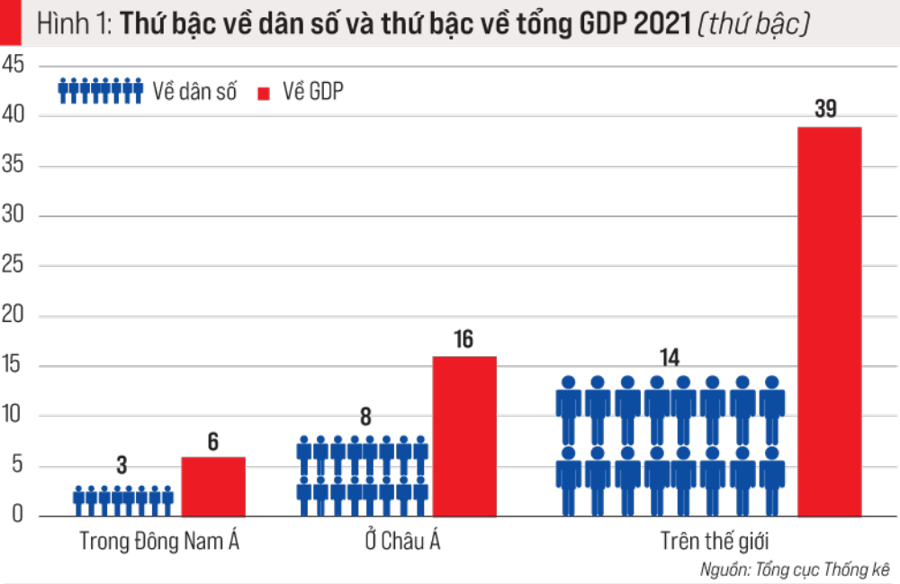

However, there are also opinions that reflect an overly proud mindset, failing to recognize that the growth rates of the past were not sufficient. Vietnam’s GDP scale is still small compared to its population rank.

As a result, the country’s rank in terms of total GDP is significantly lower than its rank by population. While some countries and territories have experienced negative population growth, Vietnam has maintained positive growth, with an average natural population increase of nearly 1 million people per year. Additionally, including mechanical fluctuations, the number of people coming to Vietnam is also significant, reflected in a population growth rate of around 0.95%, compared to a natural growth rate of 0.91%.

While Vietnam has experienced a long growth period with decent growth rates, they have not been high enough to break through. No year has seen double-digit growth, and the years with growth above 8-9% have been too few and far between.

In terms of GDP per capita, due to Vietnam’s higher population rank compared to its GDP rank, the country’s GDP per capita rank is significantly lower than its population and GDP ranks. This is the clearest indication of the “not yet rich” criterion (Fig. 2).

Vietnam’s GDP per capita has increased over the years but remains far below the world’s corresponding figure (Fig. 3).

In 2015, Vietnam’s GDP per capita was only 25.3% of the world’s average. By 2018, it had increased to 28.3%, and in 2019, it reached 30.4%. In 2020, it stood at 32.4%, and in 2021, it was 30.2%. These numbers indicate that Vietnam still faces the risk of falling further behind.

In 1988, when Vietnam’s GDP per capita was a mere $88, the country was among the lowest-income groups globally. However, by 2008, Vietnam had left the low-income group and entered the lower-middle-income group. Today, the country is striving to graduate from the middle-income group by 2025. These milestones are indeed historic. However, compared to 50 years of national reunification, 40 years of renovation, and 30 years of breaking free from embargoes and integrating with the world, these changes are still slow, indicating that Vietnam is getting rich slowly.

Regarding asset accumulation, wealth accumulation is the result of increasing GDP per capita, but it is not solely reflected in this indicator. It is also evident in many other indicators, especially those related to accumulation for development and social indicators for the present and future. Vietnam’s asset accumulation rate as a percentage of GDP over the years is illustrated in Fig. 4.

Four points about Vietnam’s asset accumulation rate are worth noting.

First, Vietnam’s rate is among the highest in the world (ranking 1st out of 11 Southeast Asian countries, 4th out of 34 Asian countries and territories with comparative data, and 8th out of 109 countries and territories with comparative data globally).

Second, the investment/GDP ratio is higher than the asset accumulation rate, while budget deficits lead to substantial borrowing.

Third, while there is a shortage of direct investment capital for production and business, a significant amount of capital is “buried” in virtual currency, gold, real estate, and corporate bonds, which are difficult to liquidate when problems arise.

Fourth, there is a tendency for “early indulgence” among a section of corrupt individuals who have become wealthy by exploiting loopholes in policies and mechanisms, as well as some who are not yet rich but engage in extravagant lifestyles.

The accumulation for social security, such as social insurance, health insurance, unemployment insurance, and elderly care, is still inadequate. The participation rate for social insurance is only 32.7%, 90.2% for health insurance, and 26.6% for unemployment insurance.

NOT YET RICH BUT ALREADY AGING

Vietnam’s population structure shift has resulted in a rapid transition through the “golden population” structure and a quick arrival at the “aging population” structure. The difference between the “golden population” and the “aging population” structures lies mainly in the dependency ratio, which is the number of dependents per 100 people of working age (15 to 60 years old). The child dependency ratio is the ratio of children (aged 0 to 14 years old) to 100 people of working age. The elderly dependency ratio is the ratio of elderly people (aged 65 years and above) to 100 people of working age. The total dependency ratio is the sum of the child and elderly dependency ratios.

If the total dependency ratio is below 50, the population structure is considered a “golden population.” If it rises above 50, it is considered an “aging population.” If the total dependency ratio is transitioning from below 50 to above 50, the population structure is shifting from a “golden population” to an “aging population.”

Vietnam’s population structure shift over time has some notable points. The country entered the “golden population” period in 2008. According to the typical transition cycle, the “golden population” period lasts for 30 years. Thus, Vietnam’s “golden population” structure (starting from 2008) could last until 2038, leaving 15 years from 2023.

However, Vietnam’s population structure shift is slightly unusual. The “golden population” structure is passing quickly, and the “aging population” structure is arriving sooner than expected (since 2011). Currently, there are approximately 13 million elderly people in Vietnam, accounting for over 13% of the total population. Among them, 1.97 million are aged 80 years and above; 7.5 million are female, and 8.1 million live in rural areas.

Vietnam’s crude birth rate has decreased rapidly. In 2022, it was 15.2%o, lower than the world’s average of 17%o. It ranked 6th out of 11 Southeast Asian countries, 22nd out of 44 Asian countries, and 52nd out of 124 countries worldwide. The country’s total fertility rate has dropped below the replacement level, reaching 2.01% in 2022. Meanwhile, life expectancy in Vietnam is on the rise. In 2022, it was 73.6 years, higher than the global average of 72 years. It ranked 5th out of 11 Southeast Asian countries, 17th out of 44 Asian countries, and 59th out of 124 countries worldwide.

Another point to note is the high rate of informal employment, which has decreased over the years with the development of enterprises but remains significant (Fig. 5). In 2022, the rate of informal employment was higher for males than females (68.9% vs. 62.3%) and higher in rural areas than in urban areas (74.9% vs. 50.3%). The rate was also high among young people and those above 50 years old (79.8% for 15-19-year-olds and 84.2% for those above 50).

The rate was highest among those without specialized skills (78.5%) but still considerable for those with some qualifications (30.5% for college graduates and above, 41% for intermediate, and 53.8% for elementary).

The sector with the highest rate of informal employment was agriculture, forestry, and fisheries (96.7%), followed by services (57.7%). The industry and construction sector also had a significant proportion (48.3%). The high rate of informal employment is a factor contributing to the “not yet rich but already aging” risk.

RESPONDING TO THE “NOT YET RICH BUT ALREADY AGING” RISK

First, it is necessary to slow down the rapid transition of the population structure from a “golden population” to an “aging population.”

This can be achieved through several measures. One way is to encourage earlier marriages for both men and women, in both urban and rural areas. Promoting early childbearing, increasing the number of children, and shortening the interval between births can also help slow down the decline in birth rates.

Encouraging these practices in areas with late marriages, low fertility rates, and low natural population growth is crucial. Additionally, it is essential to prevent and strictly handle the trafficking of women abroad and raise awareness to reduce the number of women marrying foreign spouses.

Second, it is vital to seize the opportunity presented by the “golden population” structure to increase GDP per capita and improve social security measures.

To increase GDP per capita, it is essential to focus on both increasing the total GDP with higher growth rates and, more importantly, improving the quality of growth. This can be achieved by increasing investment and labor productivity and enhancing the contribution of total factor productivity (TFP)…

https://postenp.phaha.vn/chi-tiet-toa-soan/tap-chi-kinh-te-viet-nam

Territory-based credit policy in Ho Chi Minh City shows nearly 39% growth

Credit programs, not only support and assist the poor and vulnerable, who are the main subjects of policies in Ho Chi Minh City, with capital for production and business to create livelihoods and employment opportunities, but also play a significant role in the direction of sustainable economic development, economic growth, and social security ensured by the Government.