In Thailand’s Lampang province, approximately 50% of ceramic factories have shut down. Meanwhile, in Indonesia, thousands of textile workers have lost their jobs. In contrast, producers in Malaysia believe that the decision to impose a 10% tax on the e-commerce industry has had little impact on the influx of cheap Chinese goods into the country.

For Meelarp Tangsuwana, who opened a ceramic factory 35 years ago, the situation is becoming increasingly challenging. Like many other factories in Lampang, Mr. Tangsuwana’s company specializes in producing hand-painted soup bowls, selling them for 18 baht (approximately $0.50) to food stalls throughout Thailand. However, the market is now flooded with cheap ceramic products from China, including mass-produced bowls without artistic value, priced at just over 8 baht.

“I don’t understand how they can lower their prices like that,” said Meelarp.

The desperation of producers like Meelarp is widespread in the region, where textile, cosmetics, electronics, and kitchenware manufacturers struggle to compete with their Chinese counterparts. With highly automated supply chains, Chinese companies are relentlessly seeking new markets as their domestic market slows down, significantly altering the competitive landscape in Southeast Asia.

“As Chinese products face increasing challenges in accessing Western markets, Southeast Asia is becoming an important destination,” said Muhammad Zulfikar Rakhmat, head of the China-Indonesia department at the Center for Economic and Law Studies (CELS) based in Jakarta, Indonesia.

COMPETITIVE PRESSURE FROM CHEAP CHINESE GOODS

The influx of cheap Chinese goods into Southeast Asia is largely driven by China’s position as the world’s largest e-commerce market, its new railway lines, and modern seaports. This is coupled with a complex web of free trade agreements, from the ASEAN Free Trade Area to the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which further facilitates the flow of Chinese goods into Southeast Asian markets.

“Chinese manufacturers are adept at leveraging their scale advantages and catering to consumer demands on e-commerce platforms,” said Yeah Kim Leng, a economics professor at Sunway University in Malaysia.

However, for artisans like Meelarp, the concern about the future of the Thai ceramic industry and thousands of other small and medium-sized enterprises in Thailand is growing.

As the government has not taken decisive actions such as imposing tariffs, anti-dumping measures, or cracking down on illegal practices, companies like Meelarp’s are left without a safety net.

“We, along with other handicraft businesses, now rely entirely on government protection,” the entrepreneur shared.

In the face of alarming business closures, the Thai government has recently taken a tougher stance against China after years of promoting relations with its largest trading partner through reciprocal access mechanisms, logistics investments, and visa-free agreements.

Post-pandemic, Chinese companies have injected new life into a stagnant part of Thailand’s economy. However, experts warn that Thailand, like other ASEAN countries, must now balance protecting domestic businesses with adhering to the trade agreements they have signed.

Last week, Thailand’s Minister of Commerce pledged to crack down on smuggled goods and support domestic businesses against the tide of cheap imports. Major e-commerce platforms in Thailand, such as Temu, are under strict surveillance as they are seen as enablers of the influx of cheap goods. Foreign platforms are likely to be forced to register as local businesses and face higher taxes.

THE NEED FOR DECISIVE ACTION

In late August, former Thai Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra called for protective actions for domestic businesses against cheap Chinese goods. However, many Thai businesses are still struggling to survive as the authorities’ measures have not been effective.

“They (Chinese businesses) didn’t come here to do business with us; they came to kill our businesses,” said Thongyu Khongkan, president of the Thai Road Transport Association, to This Week in Asia.

Thongyu’s anger reflects the sentiment of many businesses in Thailand, where trade between the two countries reached $105.1 billion in the first ten months of last year.

As more and more reports emerge about Thai businesses closing due to fierce price competition, the Chinese embassy in Bangkok responded with a lengthy post on social media.

“China and Thailand are good neighbors; we are like a family. China is Thailand’s largest trading partner, and we are also the largest export market for Thai agricultural products. In recent years, China has imported more than 40% of Thailand’s exported agricultural products,” the Chinese embassy in Thailand wrote on its official Facebook page. “As for cheap goods, most of them are daily consumer goods, food, health care products, jewelry, and clothing—these items don’t even account for 10% of Thailand’s total imports from China. And they are only equivalent to 50% of the agricultural products that Thailand exports to China.”

The embassy also stated that the Chinese government calls on its citizens and businesses to abide by the laws when doing business in other countries and asked the Thai government to strictly enforce local laws, support new e-commerce platforms, and seize the opportunities presented by the internet age.

However, raids by Thai police in Bangkok, seizing millions of baht worth of smuggled cosmetics and other goods from China, paint a different picture. Many Thai consumers are advocating for “buying local” to counter the impact of China’s cheap goods in the market.

Thongyu, from the Thai Road Transport Association, warned that some critical sectors of Thailand’s economy—particularly logistics—have fallen into the hands of Chinese businesses due to the so-called “zero-dollar transport” wave. This term describes a circular economy where front companies for Chinese interests pay Chinese transport providers to ship goods in trucks owned by the Chinese side.

“I used to transport durians to Laos for 80,000 baht ($2,330) per truck, but Chinese companies are doing it for a cheaper price, only 30,000 baht per trip. This is a rate that Thai businesses cannot compete with,” Thongyu said. “Moreover, Thai businesses are paying 250 baht per square meter for warehouse space, while Chinese businesses only pay 70 baht.”

According to Thongyu, many Thai logistics companies have been bought out by their Chinese competitors and are now fronts for the Chinese to evade taxes and break the law.

In Indonesia, textile workers took to the streets of Jakarta in July, urging the authorities to take supportive action against the tide of cheap clothes and textiles flooding e-commerce platforms like Shopee, Lazada, and TikTok Shop.

According to the Nusantara Labor Federation, at least 12 textile factories in the city of Nusantara closed down in the first seven months of this year, resulting in more than 13,000 job losses.

The protests prompted the Indonesian government to impose new tariffs, ranging from 100% to 200%, on several Chinese products, including textiles, clothing, footwear, ceramics, and electronics.

“If the US can impose a 200% tariff on imported ceramics or clothing, we can do the same,” asserted Indonesia’s Trade Minister Zulkifli Hasan in July.

He also warned that if Indonesia continues to be “flooded with imports,” the country’s small and medium-sized enterprises could face collapse. Officially, these enterprises contribute about 60% of Indonesia’s GDP and employ around 120 million people.

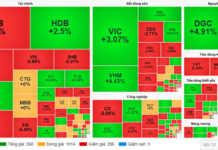

The Rise of Southeast Asia and the Mark of Vietnamese Banks

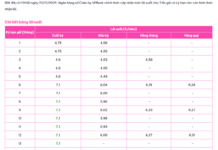

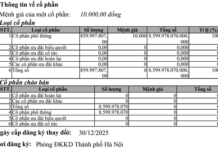

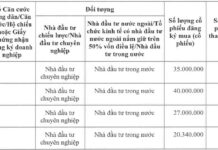

As of 2023, 34 banks are featured on the Fortune list of the top 200 largest companies in Southeast Asia, with 12 of these prestigious financial institutions hailing from Vietnam. This significant presence underscores the remarkable growth and prominence of Vietnam’s financial market within the regional landscape.

The Emergence of Southeast Asia’s Economic Powerhouse and the Pivotal Role of Vietnamese Banks

The financial prowess of Vietnam is evident in the latest Fortune rankings of the top 200 largest Southeast Asian companies, with the country boasting 12 of the 34 banks featured on the list. This significant showing underscores the remarkable growth and prominence of Vietnam’s financial market within the region, solidifying its position as a powerhouse in the industry.