The prospects of the IFC now hinge on the decrees that the government has requested to be issued urgently in August 2025. The State Bank of Vietnam has timely developed a draft decree on licensing, foreign exchange management, anti-money laundering, and counter-terrorism financing for the International Financial Center in Vietnam. Therefore, discussions, policy critiques, and suggestions for streamlined procedures are necessary to take effect in time and avoid institutional gaps. This is significant for perfecting the decree’s content at this decisive moment.

The “hour G” for the International Financial Center (IFC) in Vietnam is approaching with the imminent issuance of the framework decree. Photo: Le Vu |

The first point of contention is the $1,000 threshold for mandatory reporting in international money transfer transactions at this center. Theoretically, this regulation aims to control money laundering and prevent the financial center from being exploited as a channel for capital outflows from the country. While the $1,000 threshold is not unusual and is part of FATF R.16’s requirement for transparency in cross-border payments, it is too low compared to most transactions at the international financial center. As a result, almost all significant transactions are subject to supervision, increasing compliance costs and processing time, and inadvertently sending a signal of heavy administrative control.

The core issue lies not in the $1,000 threshold but in its implementation. This threshold only requires transactions to be accompanied by sufficient information for traceability, and demanding more would quickly overwhelm the supervising agency while not proportionally improving anti-money laundering effectiveness. Perhaps it is better to maintain the $1,000 standard to ensure international compatibility but shift the focus to supervision based on risk assessment, enhanced suspicious transaction reporting, and the utilization of RegTech/SupTech to analyze big data and timely detect abnormal signals. This is a point worth considering for adjustment in the draft decree to ensure the IFC’s competitiveness from the outset.

The second point of debate revolves around the mechanism for granting licenses to banks and branches of foreign banks in the financial center and the delegation of supervisory authority. The current draft proposes two options: (i) for the first five years, the State Bank of Vietnam directly grants licenses to commercial banks and branches of foreign banks, after which the authority is transferred to the Financial Center Supervisory Agency; or (ii) from the beginning, the authority to grant licenses is given to the Financial Center Supervisory Agency, making it fully responsible.

In terms of risk management, the first option reflects caution during the initial stage when the IFC lacks precedents and operational experience. The State Bank of Vietnam already possesses the capacity and expertise to help mitigate economic and institutional risks. The five-year period is envisioned as sufficient for the new agency to accumulate capabilities and take control, but this buffer is debatable and may be too long compared to the development cycle of a financial center.

The experience of the Astana International Financial Centre (AIFC) illustrates that significant growth was achieved within seven years of its formation. The AIFC operates under English common law, is responsible for licensing, supervision, and dispute resolution, and is entirely independent of the local central bank. This “internationally independent” model has created a sense of familiarity and safety for investors who have previously experienced transactions in major international financial centers.

In the context of Vietnam, the second option, which immediately grants licensing authority to the Financial Center Supervisory Agency, aligns with the Astana model and sends a strong signal of independence and internationalization. However, it also demands high governance capabilities from the outset. From the perspective of international investors, the second option is more attractive as it is familiar and demonstrates a substantial commitment to integration. If the first option is chosen, it is worth considering whether five years is a reasonable or overly long period, causing the IFC to miss out on rapid growth opportunities. In this case, the decree should clearly define the roadmap and timeline for the transition. This is because the licensing mechanism is not merely a technical detail but also a measure of the IFC’s level of internationalization.

Another important aspect is clarifying the objectives of the draft decree. The current goal mentions establishing the IFC to maximize international capital attraction, promote economic development, ensure safe banking operations, and prevent money laundering. Setting these four goals simultaneously may lead to an impractical situation: expecting to attract maximum capital while also demanding absolute safety. Most importantly, the core objective of the draft needs to be discussed because designing reasonable provisions becomes challenging without a clear goal.

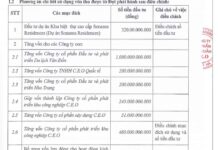

Based on the aforementioned arguments, several suggestions can be made for the decree to establish a unique legal framework for the International Financial Center. Specifically, the focus should be on licensing the establishment and operation of banks, foreign exchange management, ensuring the center’s independent operation, developing a financial services ecosystem that meets international standards, attracting international capital, technology, and high-quality human resources, and complying with international norms regarding anti-money laundering, counter-terrorism financing, and non-proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. This comprehensive approach will safeguard financial security and maintain stability within the domestic banking system.

This proposed objective has a clear structure. Beginning with the verb “to establish” and the phrase “unique legal framework,” the emphasis is immediately placed on the expected outcome, asserting that this is a separate and flexible corridor for the financial center’s operations. Notably, the phrases “international standards” and “compliance with international norms” not only signify clear references to global standards but also serve as legal anchors, providing a solid foundation for the design of the regulatory framework. Consequently, each objective is linked to a specific action, measurable, and translatable into concrete regulations, collectively shaping the decree into a policy statement.

A well-designed decree that adheres to international standards will not only unlock opportunities for the IFC in Ho Chi Minh City but also reinforce Vietnam’s position on the global financial map.

Associate Professor Dr. Pham Thi Thanh Xuan

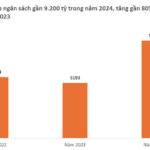

Agribank: A Leading Contributor to Vietnam’s National Budget for Sustainable Development

Let me know if you would like me to make any adjustments or provide additional content related to this topic.

As a leading force in the financial market, the Vietnam Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (Agribank) has not only solidified its position as a top contributor to the national budget but has also played a pivotal role in fostering economic and social development, particularly in the “Three Agricultures” – agriculture, rural areas, and farmers.

“Vietnam Earns $4.5 Billion Annually from Rice Exports, but Spends $12 Billion on Animal Feed Imports.”

The young entrepreneur highlights the untapped potential in Vietnam’s agricultural product development.

Taking Stern Action Against Exploitative Practices During the Implementation of Decree 178.

The Government Steering Committee urges heads of agencies and units to uphold their responsibilities and accurately identify individuals subject to the provisions of Decree 178 (as amended and supplemented by Decree 67). This involves a careful consideration of staff streamlining, enhancing the quality of the workforce, and ensuring timely implementation. It is imperative to avoid any instances of shirking responsibility or exploiting these policies.