|

A bird’s-eye view of Ho Chi Minh City.

|

Prior to the merger, Ho Chi Minh City (formerly) had an urban development plan for a multi-center city, also known as a decentralized polycentric model. This model is considered optimal for urban planning, including socio-economic, infrastructure, and transportation planning.

Globally, metropolitan regions such as Tokyo, Metro Manila, Seoul, Bangkok, Jabotabek (Indonesia), and Shanghai have all successfully implemented decentralized, polycentric planning models.

It is important to acknowledge that every major city in the world has a primary central business district or downtown area. This is where pivotal political, economic, diplomatic, financial, and multinational entities are headquartered.

Therefore, I believe that the new Ho Chi Minh City should retain its polycentric development model. The challenge lies in determining how to maintain this model and the techniques required to do so. Despite our intentions, the new Ho Chi Minh City already consists of three distinct regions: the former Ho Chi Minh City, which serves as the political, diplomatic, financial, healthcare, and educational hub; Binh Duong, primarily focused on high-tech industrial development; and Ba Ria-Vung Tau, known for its tourism and recreational offerings.

Consequently, the new Ho Chi Minh City will remain polycentric, but the question becomes how to align the new administrative machinery with this model.

Another crucial aspect is changing the perception of urban planning. Typically, the development of a province or city involves four planning schemes: socio-economic, spatial, infrastructure, and service planning.

For the new Ho Chi Minh City, it is imperative to shift the mindset by prioritizing “socio-economic planning first.” In the past, we have approached planning in reverse, starting with spatial planning, followed by transportation planning, and leaving socio-economic and cultural aspects to chance, resulting in suspended or unrealistic plans and ghost towns.

Socio-economic planning involves dividing the economy into functional zones, determining the primary function of each zone and district, and establishing the population scale and service density.

Previously, the three localities had distinct socio-economic regions defined by administrative boundaries, leading to a provincial mindset in planning. Now, with the new Ho Chi Minh City spanning nearly 7,000 square kilometers, adjustments are necessary to ensure a rational and unified approach, avoiding overlap, imbalance, and conflict.

For instance, with the Cai Mep Thi Vai port now under the jurisdiction of Ho Chi Minh City, is it necessary to build the Can Gio International Transit Port? Or should we focus on upgrading and expanding Cai Mep Thi Vai? Similarly, as Ba Ria-Vung Tau is currently the tourism hub of the new Ho Chi Minh City, should we allocate land in Can Gio for large-scale tourism development and construct a high-speed railway?

These decisions would impact the ecosystem of the biosphere reserve. The northern region of Binh Duong, including Bau Bang and Phu Giao, was intended to become a new industrial and urban center. In the context of the new Ho Chi Minh City, what function will this area serve? Can it be a hub for polluting industries? It is worth noting that all three former administrative units had three concentric urban belts: the core area, the central area, the newly urbanized area, and the outer suburban belt. With the formation of the new Ho Chi Minh City, what constitutes the center and the outskirts needs to be redefined.

Next, we must “replan the network of vital services.” This includes hospitals, schools, cemeteries, landfills, parks, and entertainment venues. The directors of the Departments of Health, Education and Training, Tourism, and Environment need to collaborate to re-envision these services in the new context.

The new Ho Chi Minh City should consider expanding, merging, upgrading, constructing, and relocating specific types of hospitals. Additionally, is it necessary for universities to be dispersed as they are currently? These considerations fall under socio-economic and service planning. It is essential to remember that services should account for at least 70% of the new Ho Chi Minh City’s economic structure.

Subsequently, we need to unify “socio-economic planning, spatial planning, and transportation planning.” These three aspects cannot be treated in isolation. Ho Chi Minh City once envisioned a “super department” to oversee these interconnected areas. However, in recent years, socio-economic planning has been the responsibility of the Ho Chi Minh City People’s Council and the Institute for Development Research, while spatial planning has fallen under the purview of the Department of Planning and Architecture, and transportation planning has been handled by the Department of Transport. This separation has contributed to issues such as flooding, traffic congestion, pollution, and urban overload. With the establishment of the new super department, we expect more streamlined operations.

A pertinent question arises: When Ho Chi Minh City operates daily, where is the focal point? Is it in the specialized departments, the wards, or the inter-ward administrative centers? This question is crucial because it directly impacts the city’s interaction with its citizens. If the focus is on the wards or inter-ward administrative centers, Ho Chi Minh City must swiftly complete the 1/500 planning coverage, providing ward leaders with technical guidelines to follow.

However, achieving comprehensive 1/500 planning coverage in a short period is challenging, especially considering the diverse socio-economic, cultural, demographic, and geological characteristics of each area. To address this, we need to establish a supporting organization for the wards and administrative centers in planning, construction, and design.

In this context, reinstating the Office of the Chief Architect as a semi-official or semi-public organization is advisable. Many countries have similar entities. This organization would serve as an advisory body not only to the leadership but also to ward and commune leaders, while the Department of Construction would assume a state management role.

Our transition has been rapid, and we may not have adequately prepared in terms of theory and establishing the necessary conditions for the operation of the new Ho Chi Minh City as a megacity.

Therefore, even if it takes time, we should develop a sustainable and long-term development strategy. The notion of Ho Chi Minh City as a polycentric city should be maintained and emphasized, not only because it aligns with the city’s new context but also because it corresponds with global trends.

Associate Professor Dr. Nguyen Minh Hoa

– 12:00 01/09/2025

The Contrasting Scenes in Saigon’s Shopping ‘Paradise’: A Tale of Two Extremes

The National Day holiday witnessed contrasting scenes in Ho Chi Minh City’s commercial areas and supermarkets: while some spots were bustling with shoppers, diners, and revelers, others remained eerily quiet despite offering eye-catching products at attractive prices.

The Master Plan: Unveiling Ho Chi Minh City’s Rosy Future with the Thu Thiem Urban Area Project

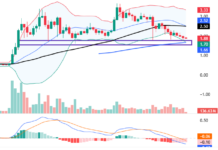

The villa area (Area II) consisting of 177 lots will have pink book certificates granted for 64/177 villas, and the adjacent residential area (Area III) with 222 lots will have 141/222 townhouses granted the same under the Low-Rise Housing Project, master-developed by Dai Quang Minh Real Estate Investment Joint Stock Company.