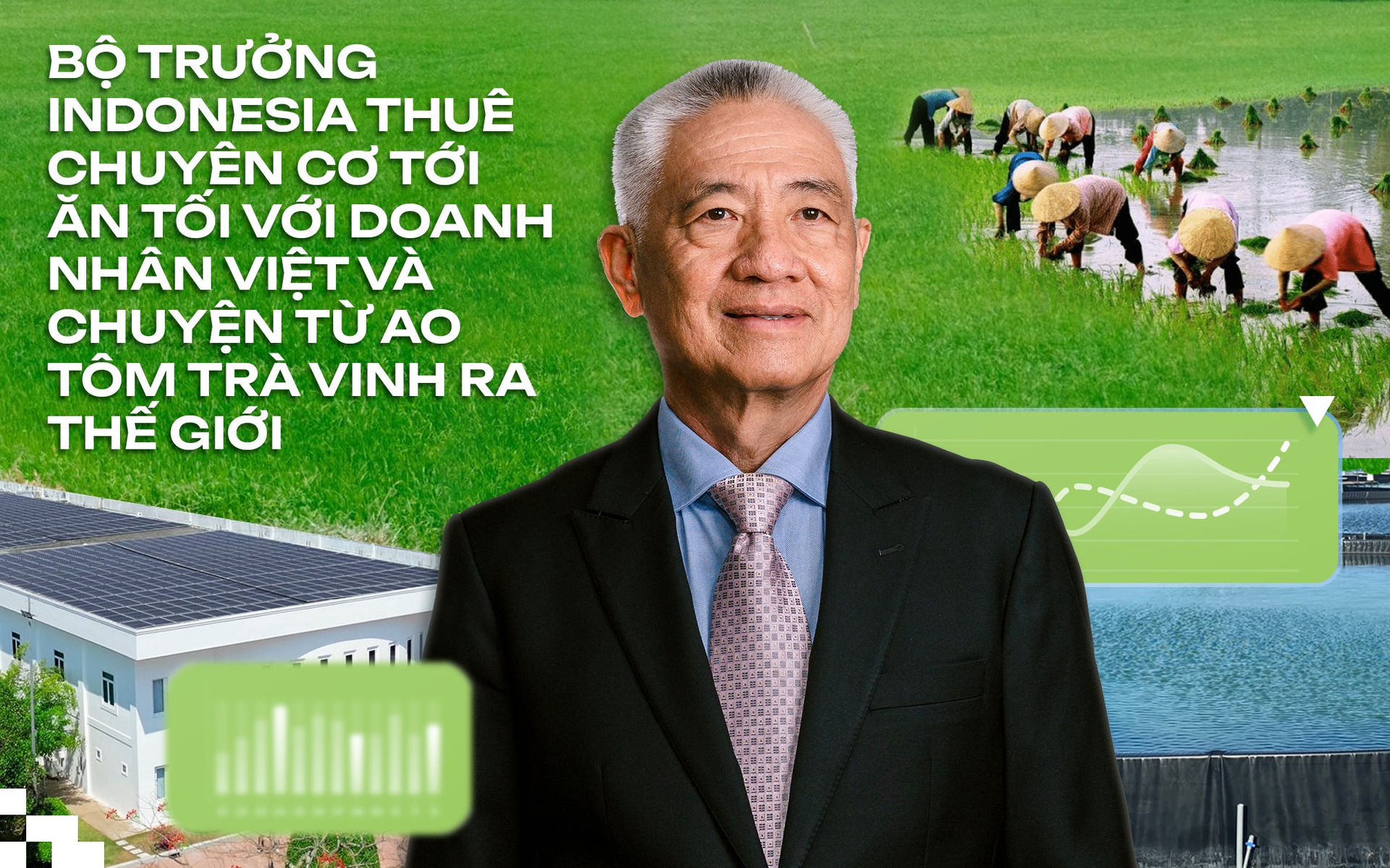

From a stellar career at IBM and Kodak to building the world’s third-largest inkjet printing enterprise in Canada, Nguyen Thanh My, despite his global success, chose to return to his roots in Tra Vinh, Vietnam. Now, in his 60s, he embarks on a new adventure: digitizing agriculture. A journey he admits is for the “truly foolish.”

Meeting him in his simple white shirt, I was curious: What made an Indonesian minister charter a private jet just to keep a promise to meet him in Singapore?

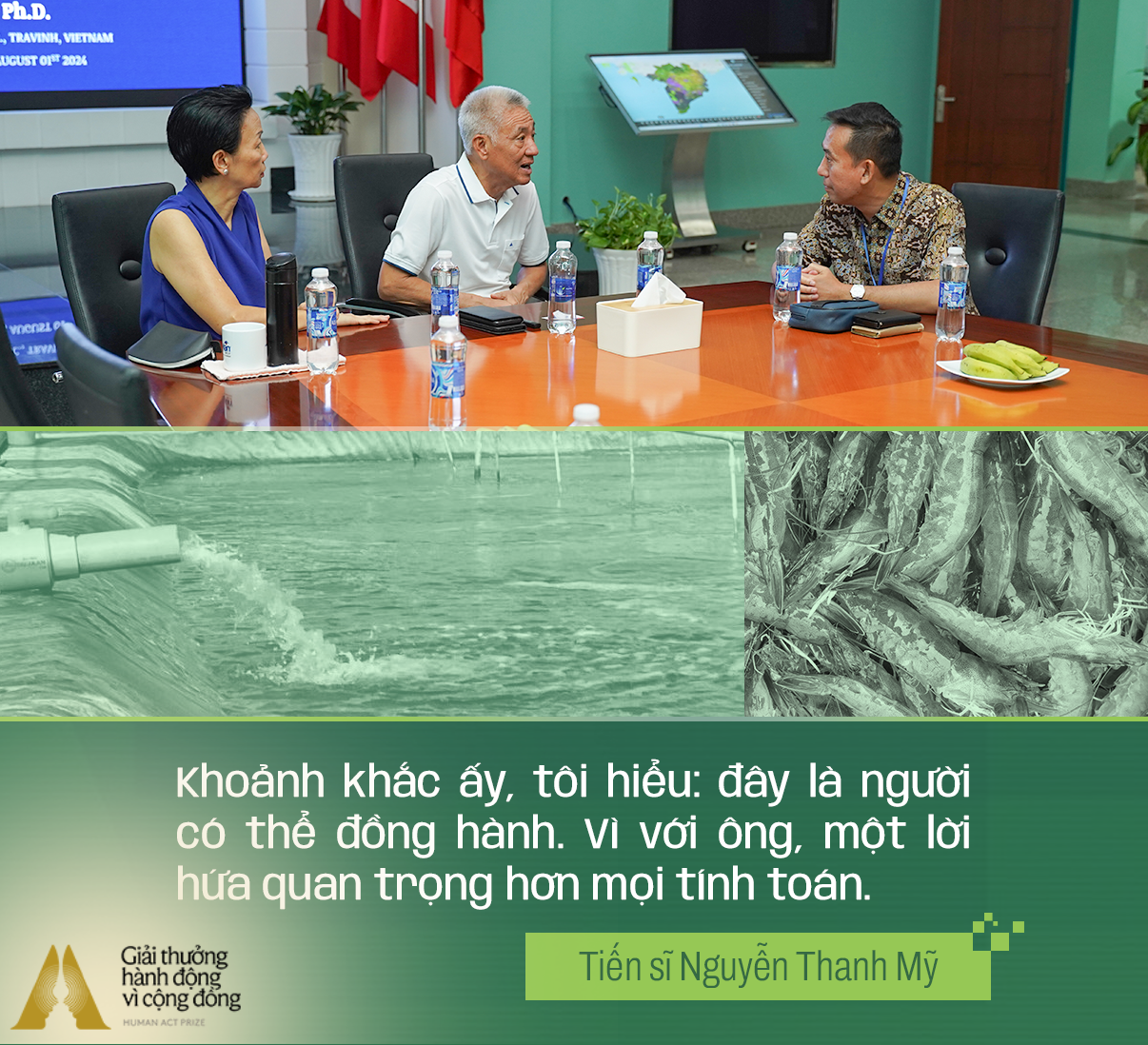

That day, my son arranged a special seafood dinner with Minister Sakti Wahyu Trenggono (Indonesian Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Affairs) in Singapore. The minister, initially flying from Nha Trang with a layover in Ho Chi Minh City, faced a delay.

Determined to keep his word, he chartered a private jet, and I joined him. At 6 PM sharp, as promised, he arrived at the restaurant, where his wife had flown in earlier from Indonesia.

In that moment, I understood: this was someone I could trust. For him, a promise was more valuable than any calculation.

In Indonesia, I began implementing the TOMGOXY shrimp farming model. Over 40 ponds, each a thousand square meters—worth millions of dollars. But this was just the start. If successful, they plan to expand to a massive 2,000 hectares.

The Indonesian government sees shrimp as a strategic industry, investing in vast farms. Deputy Minister Haeru Rahayu visited Vietnam multiple times, inspecting my company’s technology. Their eagerness for innovation led them to send delegations to scrutinize every detail before partnering.

What makes this shrimp farming model so appealing to Indonesia?

In Tra Vinh, a farmer using the TOMGOXY model on 7.5 hectares harvests over a hundred tons of shrimp annually, profiting significantly after expenses. Yields average 40–55 tons/ha/crop, 3–5 times higher than traditional methods.

The difference lies in technology: conical ponds collect waste and discharge automatically. Machines regulate oxygen and create continuous water flow. Shrimp are fed automatically based on size. Sensors, AI, and smartphone apps replace manual labor, increasing density by nearly fourfold and reducing costs by a quarter.

Compared to traditional methods, the contrast is stark. Producing one ton of shrimp used to require half a hectare of land, thousands of cubic meters of water, and double the greenhouse gas emissions of cattle farming. A costly and environmentally destructive practice. TOMGOXY changes that.

Crucially, it ensures traceability and meets international food safety standards, helping shrimp enter demanding markets like the US, EU, and Japan.

For me, it’s not just about exporting Vietnamese produce but ensuring farmers thrive on their land.

You chose not to sell solutions but to design systems benefiting farmers. TOMGOXY exemplifies this—technology replacing manual labor. But agriculture isn’t just shrimp ponds, is it?

I developed salinity intrusion monitors installed on rivers. In Tra Vinh, for two years, no one has complained about droughts or salinity. Farmers simply check their phones: pump water when it’s fresh, stop when it’s salty. A small change saving entire seasons.

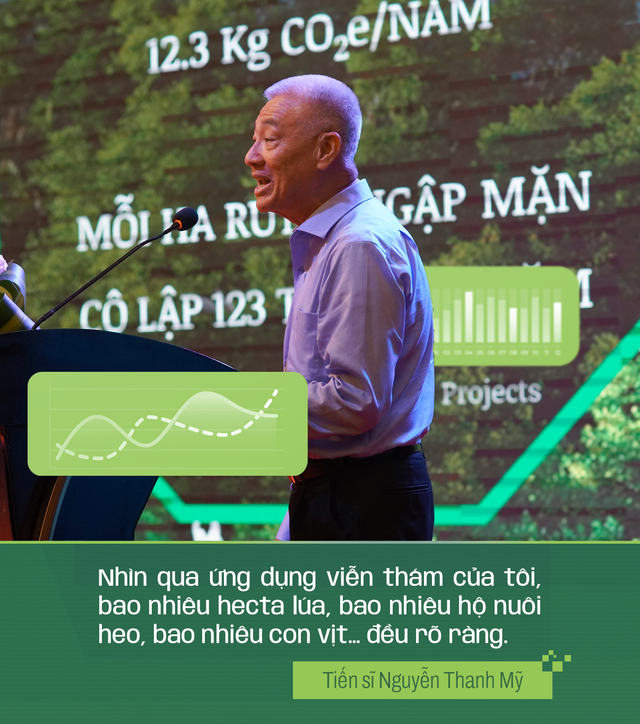

I also built a digital agriculture platform. My remote sensing app shows hectares of rice, pig farms, duck counts—all in detail.

I measure greenhouse gas emissions and monitor insect migrations, tracking brown plant hoppers. Farmers reduced pesticide use from 4–5 times/crop to one or none. Cleaner rice, healthier people.

These systems predict agricultural issues 2–3 months in advance, supporting value chain management, regional planning, and traceability. If widely adopted, they’ll digitize agriculture and promote sustainability.

These innovations seem to benefit not just farmers but also industry leaders…

Before becoming minister, Le Minh Hoan urged me to support digital agriculture in Dong Thap. I invested millions in research without expecting immediate returns. I just wanted to help.

Once, after a major storm in the North, Hoan called me at 2 AM: “Tell me where the flooding is worst so I can help immediately.”

Though my system focused on the Mekong Delta, we had Northern data. That night, my team worked tirelessly, sending critical information. He went straight to the worst-hit areas.

Seeing a minister brave storms to help farmers deeply moved me. It reminded me: choosing agriculture means committing fully.

You say you do this to help, not for profit?

Few know I export products to over 80 countries. Instead of donating money, I invest in meaningful, ethical projects. Everyone helps their country in their way. This is mine.

You invest in agriculture passionately, but have you faced challenges?

The biggest challenge isn’t farmers or businesses—it’s mechanisms.

Our applications require annual fees for updates by hundreds of engineers. The old preference for one-time purchases doesn’t fit. If they buy without ongoing support, the system fails from the start.

Digitizing agriculture requires massive infrastructure: data systems, water monitors, insect surveillance, greenhouse gas measurements. Only the government can manage this. But mechanism bottlenecks must be resolved.

I’ve been “knocking on doors” for years with little response. Recently, Resolutions 57 and 68 offer hope. Turning resolutions into reality takes work, but I’m optimistic.

While waiting, I hope many join hands. If I install an insect monitor, others add more; if I set up a water sensor, they follow.

IFAD funded many insect monitors. Binh Dien Fertilizer invested in salinity sensors. We installed hundreds of water monitors, saving countless crops. When many contribute, the picture brightens. Such efforts are still rare. We need more.

Despite TOMGOXY’s success, its large-scale adoption remains limited. Why?

In the Mekong Delta, many leading shrimp farmers prefer traditional methods, fearing change. Farmers are innovative but lack scientific foundations for breakthroughs.

Vietnam’s shrimp industry isn’t truly strong. Despite hundreds of thousands of hectares, production falls short of targets. Vietnam imports raw shrimp from India and Ecuador for processing.

Reports show annual “growth,” but farmers often fail: debt, family breakdowns.

I’ve seen areas once bustling with shrimp ponds now deserted, debts unpaid.

As someone with technology to help, how do you feel seeing this?

Honestly, I’ve spoken until hoarse, but few listen. My technology goes abroad or seeks “new fields” domestically (laughs).

Knowing farmers will lose but unable to help is painful! But I’ve learned to accept it. I do this for my homeland, my 800 employees.

Perhaps large farms and strong investments will prove effectiveness, driving change. For now, healthy shrimp seedlings ensure farmers profit, giving them capital and confidence to innovate.

Currently, over 70% of whiteleg shrimp in the Mekong Delta carry EHP disease. Undetectable early, it stunts growth, wasting investments.

Tiger shrimp are better but not thriving. I know, but… (sighs) I can’t help everyone!

You left Vietnam, succeeded abroad, then returned to a challenging path. Why?

Post-war, Vietnam faced embargoes and poverty. After graduating, I couldn’t find work. One evening, my uncle said, “Take the kids and flee by boat.”

A fishing boat carried 42 people like sardines. In the dark, stormy sea, the engine failed. For 12 days, we survived on rainwater. I thought we’d perish.

An American oil rig rescued us. Stepping on land, I vowed never to waste a moment. I believed I had a “second life.”

Despite success at IBM and Kodak, I returned to Vietnam. Canada offered comfort, but Vietnam had community, childhood memories, and warmth.

When courting my wife, I told her my dream while chopping meat: “One day, I’ll return, build factories, and help people.” Everyone laughed, thinking I was “bragging.” But hearts always yearn for home.

I returned when the dream was distant.

How did you nurture this dream abroad?

To marry, her family required a degree and stable job. I studied days, worked nights, slept 2–3 hours daily. In seven years, I earned a Ph.D. in Chemistry, joined IBM, Kodak.

In 1997, visiting Vietnam, seeing Tan Son Nhat Airport’s darkness contrasted with Korea’s brightness, I cried.

Back in Canada, I quit, started a business, and returned in 2003 with a successful company.

Was it just the dream or profit too?

Canada offered opportunities but higher costs. I thought: if it costs three times more, why not return and create jobs? Success isn’t just money—it’s knowledge, opportunities for others.

20 years ago, people called me crazy for investing in Tra Vinh. Today, I’m happier than ever. I’m the richest person—not just in money but in love and contentment.

If I could redo it, I’d choose the same path, but with less haste and more wisdom.

Why do you say that?

When building factories, material losses reached 30%. I lost $1–1.5 million but achieved my dream. A bumpy road makes the journey exciting.

Procedures were complex, but I persisted. Developing nations face challenges. I always thought: worst case, I’ll return to Canada. This gave me courage to speak truthfully and fear no failure.

Your dream now seems global, not just Vietnam?

My insect monitor—a global first—is in Japan, Thailand, Brunei. Japan bought 50 units for 47 provinces. They address a critical issue: 40% of insects vanished in a decade, threatening food security.

Domestically, challenges remain. But General Secretary To Lam said, “Science shouldn’t be cheap.” I trust the future. With enough love, even a Tra Vinh shrimp pond can reach the world.

I’m happy I took the long road: leaving to return, returning to advance further.

Unveiling the Triangle Millet Scooter: Vision-Level Pricing, 1.75L/100km Fuel Efficiency, Spacious Storage, and Smartkey Technology

This sleek scooter model offers a surprising array of features at a price point just over 30 million.

Ho Chi Minh City: Vietnam’s Megacity and Engine of Growth

In just a few days, the Ho Chi Minh City Party Congress will officially commence. This event transcends local politics, marking a pivotal moment in the nation’s development. As the first Congress following the city’s expansion through the merger with Binh Duong and Ba Ria – Vung Tau, it heralds the birth of a megacity boasting over 14 million residents. This new metropolis stands as Vietnam’s premier hub for industry, services, finance, and maritime trade.