The COVID-19 pandemic revealed a striking paradox: airline loyalty programs have transcended their role as mere marketing tools, evolving into highly valued revenue machines, often surpassing the worth of the airlines themselves. Behind these loyalty cards lies a powerful private “bank” of immense influence.

When the “Child” Outvalues the “Parent”

During the dark days of early 2020, several global airlines teetered on the brink of bankruptcy due to COVID-19, forcing them to seek massive loans to maintain liquidity and survival. With most fleets leased and ineligible as collateral, some U.S. airlines brought an unexpected asset to the negotiating table: their loyalty program subsidiaries, once thought to merely offer reward points for flights.

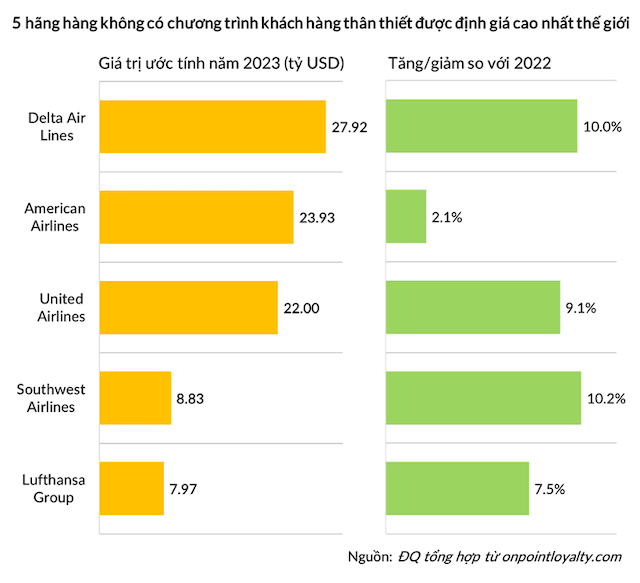

Wall Street’s valuation of these loyalty programs left many stunned. United Airlines’ MileagePlus was priced at nearly $22 billion, while the airline’s market cap stood at just $10.6 billion. Similarly, American Airlines’ AAdvantage was valued between $18 and $30 billion, dwarfing the airline’s sub-$7 billion market cap.

This disparity implies that core operations—passenger and cargo transport, with hundreds of aircraft, thousands of crew members, and a global network—are effectively valued negatively. In essence, loyalty programs have become the profit engines, while other operations incur losses.

What transformed these seemingly simple reward systems into such valuable assets?

The Surface Benefits

The most obvious advantage is customer retention, driven by the “sunk cost fallacy.” Once passengers accumulate significant miles, they’re more likely to continue flying with the same airline, even paying slightly higher fares, to maintain and grow their rewards for future flights. Switching airlines would mean starting from scratch, a psychological barrier many avoid.

Secondly, these programs are data goldmines. By tracking flight and redemption histories, airlines gain deep insights into spending habits and preferences. This data optimizes route networks, enables tailored promotions, and informs data-driven strategies.

Sophisticated Earning and Redemption Mechanisms

Initially, points were earned based on miles flown, but this led to an imbalance: passengers on long, cheap flights earned more than those on short, expensive ones. Most major airlines now use a revenue-based system, linking points to ticket cost.

Redemption has also evolved. Fixed reward rates for domestic flights, regardless of demand, often led to losses. Dynamic pricing now adjusts reward costs based on demand, mirroring cash ticket prices.

Airlines also devalue miles over time, creating “inflation” in the rewards economy. For instance, a ticket once costing 9,000 miles might now require 9,600, prompting passengers to redeem miles before further devaluation.

Yet, even these sophisticated mechanisms don’t fully explain why loyalty programs outvalue airlines.

The Money-Printing Machine: Airlines as “Central Banks”

The true value lies in selling miles to third-party partners. Customers earn miles not just from flights but from spending with airline partners—banks, hotels, car rentals, retailers—transforming airlines into financial powerhouses akin to central banks.

Airlines sell billions of miles to partners for cash, which partners use to incentivize spending. This boosts partner revenue while airlines secure upfront cash. When passengers redeem miles for flights, airlines often benefit from unsold seats that would otherwise go empty. Many miles expire unused or lose value due to inflation, further boosting program profitability.

This model gives airlines control beyond that of central banks. While central banks manage money supply, airlines control both the creation and use of their currency (miles), dictating redemption rates and effectively setting “prices” for flights.

Market evidence supports this. In 2020, Delta’s SkyMiles ($28B) secured a $9B loan, American’s AAdvantage ($24B) a $10B loan, and United’s MileagePlus ($22B) a $6.8B emergency loan.

Vietnamese Airlines

In Vietnam, Vietnam Airlines (HVN) operates Lotusmile, Vietjet (VJC) has SkyJoy, and Bamboo Airways (BAV) offers Bamboo Club.

Lotusmile members earn miles through partnerships with Grab, Accor Hotels, Booking.com, VinID, Techcom Securities, and co-branded credit cards from Vietcombank, Sacombank, VPBank, VIB, and Standard Chartered.

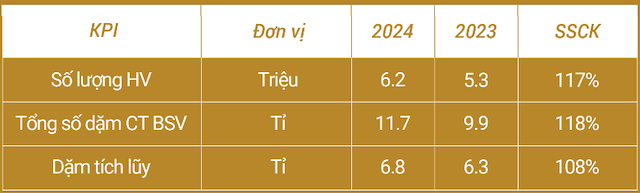

In 2024, Lotusmile had 6.2 million members, up 17% YoY, with 6.8 billion miles earned, an 8% increase.

Key Lotusmile statistics. Source: 2024 Annual Report.

|

Recognizing the potential, Bamboo Airways introduced a status match policy, offering elite tiers to competitors’ premium members, attracting VIP customers to experience their services.

While global and Vietnamese airlines operate loyalty programs, monetization levels lag U.S. counterparts. This untapped potential offers high-margin, stable cash flows, resilient even during crises, contrasting with the capital-intensive, low-margin aviation business. Many airlines leverage risky aviation operations to fuel their loyalty programs—a near-perfect money-making machine.

– 07:00 25/10/2025

Tobacco Industry’s Decline: Experts Propose Recovery Strategies for Vietnam’s Once-Lucrative Sector

Recently, the Vietnam Beer-Alcohol-Beverage Association (VBA) chaired and collaborated with the Vietnam Chamber of Commerce and Industry (VCCI) and the Vietnam Association of Foreign Invested Enterprises (VAFIE) to organize a seminar titled: “Stimulating Consumption to Drive Economic Growth – Perspectives from the Beverage Industry.”

The Golden Land Grab: Đà Nẵng’s Decade-Long Struggle with Abandoned Projects

A slew of large-scale projects in Da Nang have been stagnant for over a decade despite receiving investment certificates and investment policy approvals from the city. A number of these projects have even ceased operations.