Major rice importing markets are increasingly focused on food self-sufficiency, reducing their reliance on imports. As a result, Vietnam’s rice industry must adapt and pivot to remain competitive.

Dual Challenges

Recent reports from the Philippines indicate that President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. has extended the suspension of regular rice imports until December 31, 2025. Previously, the country halted imports in September and October to stabilize domestic rice prices.

Rice varieties not commonly grown by Filipino farmers will remain outside the scope of this regulation. The suspension period may be shortened or extended based on actual demand.

This move means that in 2025, the world’s largest rice importer—and Vietnam’s biggest customer—will halt imports for four consecutive months.

Beyond this temporary measure, the Philippines has also adopted a long-term strategy to reduce its dependence on imported rice. The government has approved a $3.7 billion investment package to upgrade the entire rice sector, including farmer support, yield increases, and logistics improvements.

The Philippines aims to achieve 84% rice self-sufficiency by the end of 2026 and 90% by 2028. This will significantly reduce import demand from Vietnam in the coming years.

Businesses showcase rice products to domestic and international wholesalers

Starting in 2026, the Philippines will implement an automatic import tariff mechanism based on global rice price fluctuations, ranging from 15% to 35%. Tariffs will increase by 5 percentage points if international rice prices drop by 5%, and decrease accordingly if prices rise by 5%. This mechanism adds competitive pressure on imported rice, potentially disadvantaging Vietnamese rice.

Additionally, Indonesia, Vietnam’s second-largest rice trading partner, has announced plans to achieve rice self-sufficiency by 2025, with an expected surplus of 4–5 million tons.

Indonesia’s Logistics Agency (BULOG) reported that approximately 30,000 tons of stored rice have spoiled due to record-high stockpiles of 4.2 million tons. This excess inventory further reduces import demand.

On the supply side, rice prices in India, the world’s largest exporter, are declining due to record-high stockpiles. In the first half of 2025, India’s average rice inventory reached 37 million tons, significantly higher than previous years, putting downward pressure on global rice prices.

Amid these dual challenges—reduced export opportunities and capital shortages due to delayed VAT refunds—Do Ha Nam, Chairman of the Vietnam Food Association (VFA), stated that Vietnamese businesses must accept the situation and closely monitor developments.

Proactive Diversification

During the Philippines’ rice import suspension, businesses have proactively diversified into other markets rather than relying solely on Filipino customers.

The rice industry has also identified new export markets and is meeting high domestic demand following storms in Central and Northern Vietnam. “Our harvest season has ended, and while inventory is limited, prices remain low,” added the VFA Chairman.

Nguyen Vinh Trong, Director of Viet Hung Co., Ltd. (Dong Thap), noted that the Philippines accounts for about 15% of the company’s export volume. The import suspension will only slightly reduce their output, as the Philippines continues to import glutinous and Japonica rice. Viet Hung has also increased exports to China, the Middle East, and Africa, stabilizing rice prices despite current lows.

Some businesses suggest that the government should liberalize rice exports, enabling smaller-scale but higher-value exports. This would address the industry’s output challenges and support farmers. Huynh The Vinh, CEO of Vinh Hien Farm, shared that his company is exploring niche markets. Recently, they exported a container of small-packaged rice to Saudi Arabia, moving beyond traditional 50 kg sacks.

According to Vinh, as countries prioritize food self-sufficiency, they will import only specialized rice varieties like ST 25 and Japonica. Businesses are focusing on high-value niche markets such as Europe, Japan, and the Middle East.

Processed rice products like noodles, cakes, and dried pho also offer significant potential, adding value to Vietnamese rice beyond raw, unbranded exports.

Nguyen Ngoc Luan, CEO of Global Trade Link Co., Ltd., has been exporting rice to Australia for the past four months and sees substantial potential. He exports high-quality, branded rice at $1,100–$1,200 per ton. Beyond the Asian community, local Australians are increasingly incorporating rice into their diets for starch diversity.

Luan observed that while there are ten times more Vietnamese than Thais in Australia, Vietnamese rice lags in branding compared to Thai and Cambodian rice. Historically, Vietnam has focused on low-cost, high-volume markets like the Philippines and Indonesia. Luan believes it’s time for Vietnam to target higher-value markets with greater profit margins.

He also noted that ST 25 rice, despite winning the “World’s Best Rice” award, has faced negative media coverage, raising concerns about counterfeit products and impacting its global reputation.

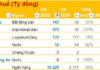

According to the Ministry of Agriculture and Environment, rice exports in October 2025 reached approximately 421,100 tons, valued at $216.9 million, with an average price of $515 per ton. In the first ten months of the year, exports totaled 7.2 million tons, worth $3.7 billion, down 6.5% in volume and 23.8% in value compared to the same period in 2024. Export value to the Philippines in the first nine months of 2025 decreased by 27.1% year-on-year.

“Vietnamese Food Association Chairman Comments on ‘Unusual Move’ by World’s Top Rice Importer”

Vietnam’s top rice market, accounting for 40% of the country’s exports, remains temporarily closed with no confirmed reopening date.