Vietnam’s Railway Renaissance: A Dream of Revival

According to the General Statistics Office, Vietnam’s railway industry once boasted a proud beginning. In 1881, the first railway line in Vietnam and Indochina, spanning 71km from Saigon to My Tho, was inaugurated, laying the foundation for a new transportation system.

Within just half a century, by 1936, the network had expanded to approximately 2,600km, covering almost the entire country. It became one of the earliest established railway systems in the region, with relatively synchronized infrastructure, technology, and workforce.

At one point, railways held a pivotal role in transportation, capturing up to 30% of the market share and significantly contributing to socio-economic development, national defense, and security. However, over time, this prominence faded.

Railways once dominated transportation, holding a 30% market share. Image: TL

|

Passenger and freight volumes have continuously declined, with the railway’s share in the transportation sector shrinking. Post-Covid-19 challenges compounded: aging infrastructure, limited service capacity, and fierce competition from road and air transport have eroded the railway’s advantages.

By 2023, the national railway network stretched 3,315km, including 2,647km of main lines and 515.46km of station and branch lines, with approximately 84% still using the 1,000mm gauge. In 2024, the industry served over 7 million passengers, transported 5.16 million tons of cargo, and generated nearly VND 9.7 trillion in revenue. However, its market share remains modest due to slow speeds, limited capacity, and outdated infrastructure.

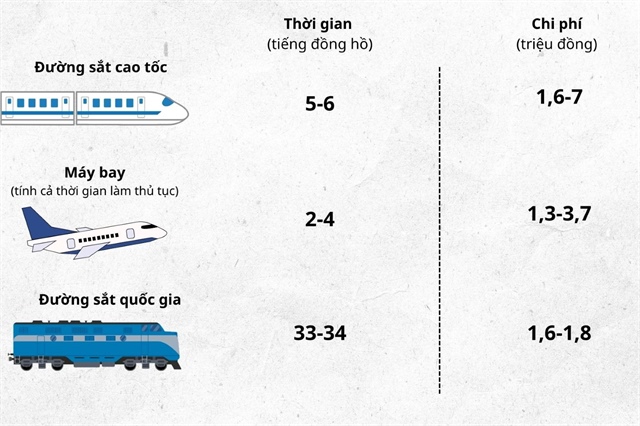

Daily, thousands of passengers still travel by train across Vietnam, from Ho Chi Minh City to Hanoi, a journey of over 33 hours, often due to a lack of more convenient options. Behind this patience lies a critical question for the railway industry: How can it not only sustain operations but also reclaim its rightful place in the modern economy?

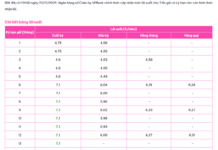

Comparing national railways, high-speed rail, and air travel. |

In late 2024, the National Assembly officially approved the investment plan for the North-South high-speed railway. Spanning 1,541km from Ngoc Hoi Station (Hanoi) to Thu Thiem Station (Ho Chi Minh City), designed for speeds up to 350km/h, it will allow passengers to “enjoy Hanoi pho in the morning and Saigon broken rice in the evening” with just 5-6 hours of travel.

Recently, the Government also approved adjustments to the Railway Network Development Plan for 2021-2030, with a vision to 2050. The new plan adds the Hanoi – Quang Ninh high-speed line, upgrades seven existing national railway lines, and promotes research on domestic and cross-border routes connecting seaports, China, Laos, and Cambodia.

This comprehensive strategy is more strategic, aiming to connect seaports, industrial zones, airports, and urban areas in a way the infrastructure sector has long awaited.

According to Dr. Nguyen Manh Hung, Senior Lecturer in Supply Chain and Logistics Management at RMIT University Vietnam, this plan sends a clear message about national infrastructure investment priorities, positioning Vietnam as a regional logistics and economic hub amidst the increasingly interconnected Southeast Asian production and trade network.

Regional corridors like Hanoi – Lao Cai – Kunming (China) and Vientiane (Laos) – Vung Ang will create international transport axes, turning Vietnam into a gateway for the Greater Mekong Subregion. If the Vientiane – Vung Ang route is implemented synchronously in both Laos and Vietnam, the East-West corridor could be activated.

However, a well-designed plan alone is not enough to guarantee success. To avoid past delays, the railway industry must address institutional bottlenecks, adopt suitable financial mechanisms, and ensure tangible implementation progress.

MSc. Tran Hoang Nam, Head of Real Estate, School of Economics, University of Economics and Finance (UEF), believes that Vietnam must view railways as an ecosystem encompassing infrastructure, services, logistics, and urban development, rather than isolated projects.

This perspective leads to three key strategies. First, a “dual network” model, where the North-South high-speed rail becomes the backbone for inter-regional passenger transport, while the existing 1,000mm gauge system is selectively upgraded for freight and international intermodal transport.

Second, positioning railways as a “green backbone,” linking development with emission reduction goals, thereby accessing green financing from international institutions. Third, integrating railways into urban and logistics planning through the TOD model, transforming stations into drivers of urban economic development and generating revenue for infrastructure investment.

According to this expert, the railway industry should also focus on its natural advantages, transporting medium to long-distance passengers (300-800km) and large freight volumes along key economic corridors.

Simultaneously, the industry must shift from a “request-grant” approach to a “public infrastructure business” model, ensuring cost transparency, applying public service contracts for loss-making routes, and clearly defining commercial segments to attract investors.

Modernizing Vietnam’s railways requires clearing many bottlenecks. Image: VNR |

“Awakening” with Capital, Mechanisms, and Governance

According to Mr. Nguyen Manh Hung, instead of spreading resources thinly, Vietnam should prioritize investment along corridors, focusing on projects offering immediate connectivity and trade benefits, rather than simultaneously implementing costly mega-projects.

Dr. Scott McDonald, Lecturer in Supply Chain and Logistics Management at RMIT University Vietnam, agrees.

He believes the North-South high-speed railway is a necessary long-term step, but for success, Vietnam must first complete metro and urban rail systems in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City.

These projects are moderately sized, lower in cost, and offer immediate congestion relief, while helping authorities gain operational, coordination, and governance experience—crucial before embarking on national-level projects.

Highlighting the need for improved governance, Mr. Hoang Nam identifies four major barriers in current railway planning. The first is the “every man for himself” approach, where railway planning often overlaps or conflicts with land use, urban, and seaport planning due to a lack of a coordinating authority.

He proposes establishing or upgrading a specialized railway agency, similar to those in Japan or South Korea. Additionally, the state could implement a responsibility-sharing mechanism, where localities benefiting from stations and urban development linked to transport must commit to land clearance, land allocation, and co-financing connecting infrastructure.

The remaining three barriers also hinder progress. Limited project preparation quality and technical capacity result in incomplete data, insufficient financial and risk analysis, making it difficult to meet bank or investor funding conditions.

Financial mechanisms also lack stability, from service pricing and subsidies to risk-sharing, deterring private sector participation. Policy inconsistency across administrations, with major projects frequently adjusted or halted, further erodes market confidence.

The North-South high-speed rail and planned railways could revive modernization dreams. Image: AI

|

Capital is a significant challenge for the railway industry. With massive investment needs, Vietnam cannot rely on a single source; public funds must remain dominant, including central budget and concessional ODA. Additionally, infrastructure bonds, green bonds, and local co-financing through land revenues are crucial mobilization tools.

However, public funds cannot cover everything, so an improved public-private partnership (PPP) model is essential. Mr. McDonald suggests the state contribute 80% through available budgets; private entities build infrastructure and develop real estate around stations; implement technology transfer incentives for technical autonomy by 2045; and establish a railway infrastructure bank providing long-term low-interest loans.

Mr. Tran Hoang Nam adds that PPP should only apply to components with clear cash flows, such as depots, logistics centers, or commercial stations, while the main line, with higher risks and unstable cash flows, should remain state-managed.

Another critical component is leveraging land value around stations through “land value capture.” Rapidly increasing land values can offset investment costs if the state recovers land early, then auctions it, develops mixed-use complexes, or reinvests fees in infrastructure, as seen in Japan, South Korea, and Hong Kong.

Furthermore, Vietnam could establish a national railway and urban infrastructure development fund, pooling budgets, long-term bonds, and resources from international financial institutions. This fund would enable long-term programmatic investments, reduce fragmentation, and address slow disbursement issues.

“The new phase’s challenge is not just ‘which line to build,’ but ‘how to build it so railways become a competitive, sustainable pillar of the national transport system,'” Mr. Nam notes.

Without addressing governance barriers—from institutions, project preparation capacity, financial mechanisms, to policy stability—even the most ambitious railway plans risk remaining on paper.

Therefore, capital solutions must be viewed as a composite structure, with public funds as the backbone, selective PPP application, infrastructure bonds as supplements, and land value capture around stations. All must operate within a transparent, consistent governance framework for railways to become a competitive, sustainable pillar of the national transport system.

With clear direction, stable mechanisms, and a feasible capital mobilization roadmap, Vietnam’s railway industry has a chance to revive, playing a larger role in logistics and green transport if implementation barriers are effectively addressed.

Gia Nghi

– 07:00 19/11/2025

Hanoi Plans 3,000-Hectare Development to Create World-Class International Park

Hanoi is exploring the planning of a vast 3,000-hectare area in Dong Anh and Phu Dong communes to create world-class entertainment hubs, modern thematic parks, and international-standard recreational centers. The initiative also aims to develop lush green spaces along the banks of the Red River and Duong River, enhancing the city’s natural and urban landscape.