Illustrative image

The U.S.’s temporary tariff exemption on coconuts and various agricultural products has sparked optimism for the Philippines’ key export sector. However, the benefits of this policy have yet to reach small-scale coconut farmers—the backbone of the supply chain who bear the most significant risks.

In Quezon, the nation’s coconut production hub, farmers report that selling prices have remained largely unchanged since the 19% U.S. tariff was lifted in mid-November.

Ellizer Manza, who has tended his family’s 2-hectare coconut farm for nearly 60 years, notes no tangible improvements. He argues that if the tariff exemption were truly beneficial, the price of coconut meat—the primary product sold by local farmers—should have increased.

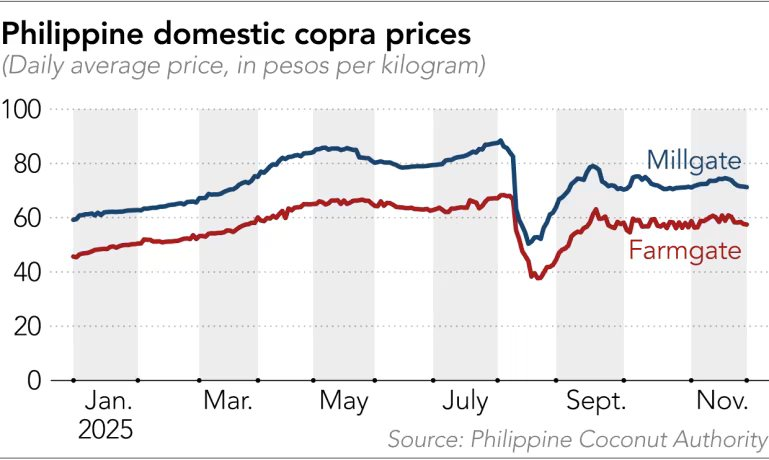

Instead, he observes persistent stagnation, with farmgate prices remaining flat. Farmers’ livelihoods continue to depend on harvests spaced over six weeks, supplemented by side jobs like fishing or rice farming to sustain their income.

The Philippines is the world’s second-largest coconut producer after Indonesia, with approximately 3.5 million farmers reliant on this crop. Quezon contributes about 10% of the national supply. Last year, the U.S. imported $633 million worth of coconut products from the Philippines, accounting for nearly a quarter of the sector’s total exports.

When Washington eliminated tariffs on agricultural goods, including coconuts and derivatives, Philippine officials expressed optimism. Trade Secretary Cristina Aldeguer-Roque stated that reduced import costs would safeguard livelihoods for millions of farmers, sustain jobs in the value chain, and create opportunities for rural communities dependent on exports.

Coconut meat prices in the Philippines remain unaffected by tariff concessions.

However, economists suggest the actual impact may fall short of expectations. IBON Foundation, a Manila-based economic consultancy, attributes this optimism primarily to “relief” after months of uncertainty rather than substantive changes.

The organization’s report highlights that the tariff exemption is not exclusive to the Philippines, as other tropical coconut exporters also benefit. Thus, the Philippines’ competitive edge remains largely unchanged, while critical factors like crop yields, product quality, and deep processing capabilities are more decisive for enhancing export value.

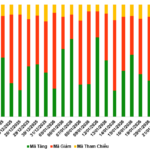

Both farmers and analysts agree that the Philippine coconut industry’s challenges stem not from tariffs but from outdated production structures. Most of the country’s coconut output is still sold as dried coconut meat or crude oil—low-value products vulnerable to global market fluctuations.

In contrast, Indonesia and Vietnam have advanced high-yielding varieties, modernized farms, and invested in deep processing to capture higher margins from products like virgin coconut oil, coconut sugar, and activated charcoal.

According to development economist Ella Oplas of De La Salle University, while the U.S. tariff exemption may boost demand for Philippine agricultural products, there’s no guarantee that smallholder farmers will reap the benefits.

She points out that intermediaries capture much of the value, leaving farmers with a small share. Traders buy at low prices and sell at significantly higher rates, concentrating surplus value among purchasing companies. Consequently, farmers struggle to improve their income despite their hard work and dedication.

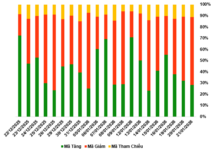

As of late November, the government-reported farmgate price for coconut meat was 57.52 pesos/kg, while traders sold to factories at 71.29 pesos/kg. Despite a 26% year-to-date increase, the price gap between intermediaries limits farmers’ gains.

Adrian Austria, a coconut meat trader earning around $2,000 monthly, acknowledges that farmers need greater support, particularly in adopting advanced agricultural techniques and diversifying income sources.

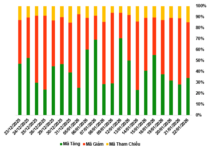

In Vietnam, after record-high prices, fresh coconuts have seen a sharp decline. In August, they sold for 180,000 VND/dozen (12 coconuts), but now traders offer only 40,000 VND/dozen.

This trend is widespread in Vietnam’s coconut-growing regions. Exporters confirm that current prices are equivalent to previous low seasons, ranging from 40,000 to 50,000 VND/dozen.

Source: Nikkei