The shift from a centrally planned economy to a market-driven one seems straightforward, yet the reality is far more complex. Could this be due to the inertia of entrenched mindsets, habits, and cultural behaviors that resist change?

The State holds absolute authority over land, tightly controlling its use, duration, pricing, and reclamation. Photo: N.K |

First, what distinguishes “management” from “governance”?

Here, we discuss state management versus national governance. During the era of centralized economic planning, the State held absolute authority, owning essential assets and production resources, including land, infrastructure, and factories. Thus, it naturally managed and controlled all socio-economic activities, termed “state management.” Other entities were either extensions of the State or merely compliant and dependent.

Over decades, the economy transitioned to a market mechanism, giving rise to private and non-state sectors that now play pivotal roles. This new landscape allows the State to influence indirectly without direct intervention. Consequently, all entities, including the State, must operate within legal frameworks, replacing administrative commands. This holistic approach is termed “national governance,” essential for aligning economic and social development.

The imperative shift to national governance

Today, both policy frameworks and societal perceptions emphasize innovation by businesses and citizens as the growth engine. However, innovation thrives only in environments of freedom, equality, and opportunity—conditions the State must establish and uphold through robust policies and laws.

|

Policymakers still grapple with the legacy of “state management,” transitioning from “subsidized control” to “regulated oversight.” While the shift to governance is conceptually clear, implementation remains challenging due to systemic barriers. |

Despite decades of reform, objective prerequisites for governance exist. Private and civil sectors operate autonomously, yet State intervention remains ambiguous, often conflicting with stakeholders’ rights and interests. For instance, recent consultations on amending Decree 83/2014 for petroleum business highlighted diverging views. One side advocates strict State control over this strategic commodity, while the other argues for market-driven pricing, ensuring business autonomy and consumer welfare.

This reflects policymakers’ struggle to shed the “state management” mindset, transitioning from “subsidized control” to “regulated oversight.” While the shift to governance is conceptually clear, implementation remains challenging due to systemic barriers.

What challenges must be overcome?

The most significant hurdle lies in land governance laws and institutions, particularly regarding property ownership and commercial rights. Despite Land Law revisions, the State retains absolute land ownership. While land use rights have expanded, the State still controls land purpose, duration, pricing, and reclamation. These rights are further constrained by multiple planning layers, increasingly favored by state agencies.

|

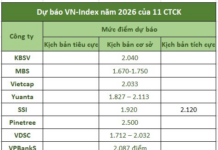

Recent discussions on “national governance,” “development governance,” and the “developmental State” offer promising institutional models for accelerated growth. With legal reforms underway, these revolutionary ideas may soon materialize into concrete actions in 2026 and beyond. |

How does this impede the transition to innovation-driven national governance?

Innovation stems from individual motivation, not structures or infrastructure. Naturally, individuals innovate when inspired and empowered, not coerced. This requires freedom, guaranteed rights, and stable trust. For businesses, land allocation must respect market-driven commercial rights, ensuring stable property ownership independent of State administrative decisions—a principle applied in market economies.

Another critical institutional barrier is the State’s role shift from “controller” to “facilitator.” The State-society relationship must evolve from hierarchical to partnership-based, emphasizing autonomy, transparency, and accountability. While “state management” persists in specific areas like law enforcement and defense, development activities should embody governance principles.

To realize this, two legal mechanisms are essential: First, as the National Assembly reduces detailed intervention in government operations, a Constitutional Court must ensure adherence to the rule of law, preventing overreach. Despite the 2013 Constitution’s Article 119, this court remains unestablished.

Second, the Constitutional Court would safeguard citizens’ rights by interpreting laws and resolving conflicts between legislative and executive branches, ensuring no state action violates constitutional rights. This would expand individuals’ legal recourse.

These issues are timely, given General Secretary Tô Lâm’s directive to review the 2013 Constitution for potential amendments aligning with Vietnam’s new realities.

Recent discussions on “national governance,” “development governance,” and the “developmental State” offer promising institutional models for accelerated growth. With legal reforms underway, these revolutionary ideas may soon materialize into concrete actions in 2026 and beyond.

Attorney Nguyễn Tiến Lập (Member of NHQuang Law Firm and Associates, Arbitrator at the Vietnam International Arbitration Center)

– 16:00 05/01/2026

Resolving 54 Pending Projects in Khanh Hoa: Urgent Action Demanded

The People’s Committee of Khanh Hoa Province has mandated that all departments and agencies conduct a thorough review, address challenges, and definitively resolve the 54 prolonged pending investment projects. Additionally, they are to assess the accountability of the involved organizations and individuals.

“High-Level Meeting Convenes to Discuss Critical Land Matters”

At 2 p.m. today, [date], Deputy Prime Minister Tran Hong Ha will chair a meeting to discuss the amended Land Law with the attendance of leaders from various ministries, sectors, and local authorities.