Venezuela boasts one of the world’s largest oil reserves. However, for years, converting this underground treasure into tangible revenue has heavily relied on where Venezuelan crude oil can be exported, amidst ongoing sanctions and political instability.

Recent developments involving President Nicolás Maduro—allegedly detained by U.S. forces—have sparked predictions of significant shifts in Venezuela’s oil industry. Before new scenarios unfold, the country’s crude oil export landscape in recent years reveals a heavy dependence on a handful of key markets.

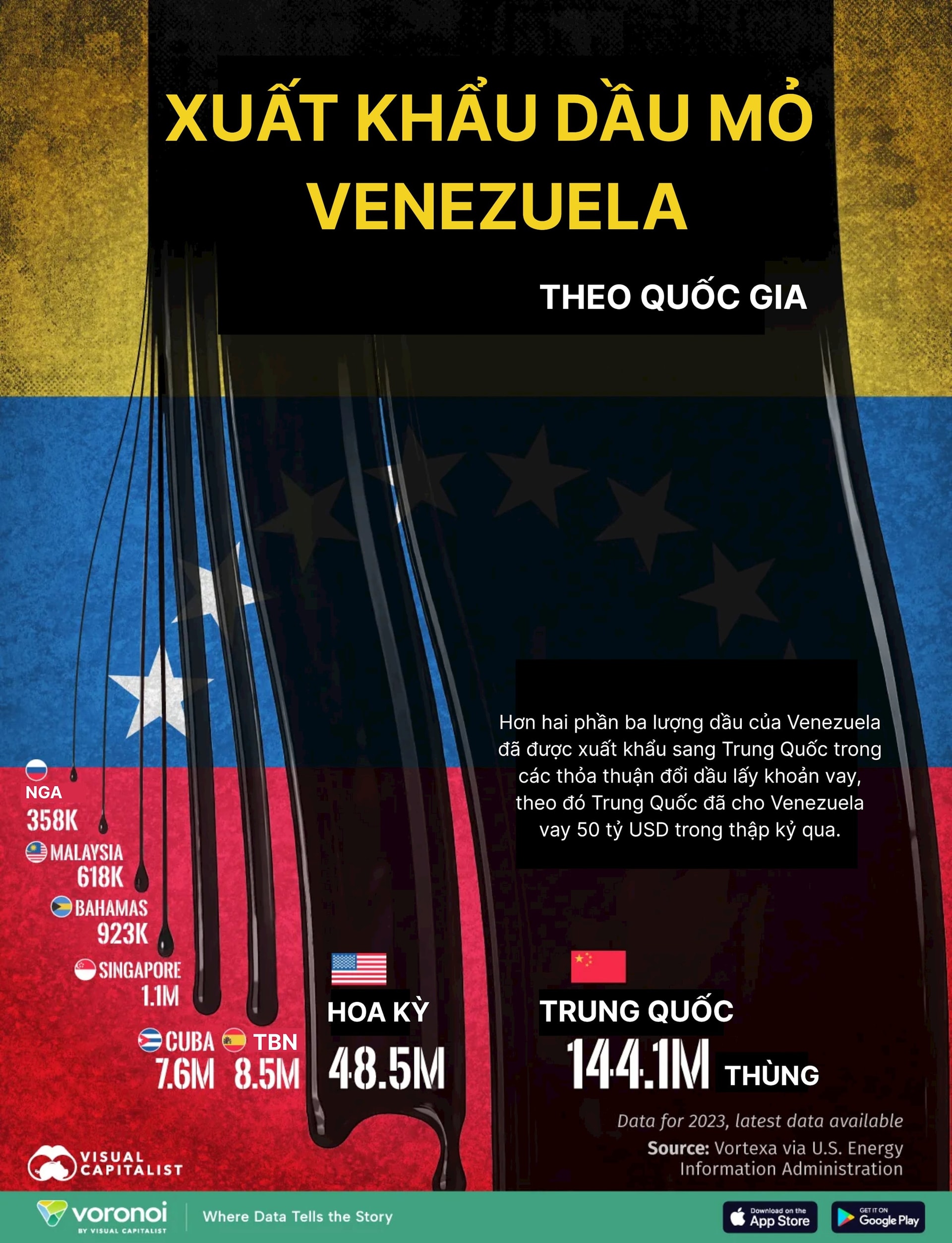

According to 2023 data from Vortexa, compiled by the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), Venezuela exported a total of 211.6 million barrels of crude oil. Notably, over 90% of this volume was consumed by just two countries: China and the United States.

China emerged as the largest destination for Venezuelan crude, importing approximately 144 million barrels in 2023, accounting for 68% of Venezuela’s total crude oil exports. The U.S. followed with 48.5 million barrels, representing about 23% of Venezuela’s total oil export revenue for the year.

Beyond these two markets, other countries imported Venezuelan oil but on a significantly smaller scale. Spain purchased around 8.5 million barrels, while Cuba imported 7.6 million barrels in 2023. The remaining markets held a negligible share in the export structure.

The oil relationship between Venezuela and China is uniquely rooted, becoming pronounced after the U.S. imposed stringent sanctions on Venezuela’s state-owned oil company, PDVSA, in January 2019. These measures severed Venezuela from the U.S. financial system and severely restricted cash-based oil transactions.

In this context, Venezuela shifted much of its export operations to a “oil-for-loans” model. China became the central partner in this scheme, lending Venezuela nearly $50 billion over the past decade, with approximately $10–12 billion still outstanding. Instead of cash payments, Venezuela repays China with crude oil shipments.

Although Venezuelan crude is primarily heavy and extra-heavy—types that are harder to refine and yield fewer high-value products like gasoline and diesel—this aligns with China’s needs. Refining heavy oil produces significant amounts of asphalt, essential for China’s large-scale infrastructure projects. Thus, Venezuelan oil becomes a cost-effective supply, perfectly matching the demand structure of the world’s second-largest economy.

However, this dynamic could shift if the U.S. increases its influence or gains deeper control over Venezuela’s oil sector. In such a scenario, China would likely seek alternative oil sources from established partners like Russia and Iran, or from Canada, which also produces similar extra-heavy crude oil.

“Combining Venezuela’s and America’s oil, we would control 55% of the world’s oil supply,” declared Donald Trump.

As global geopolitical tensions persist, the question extends beyond Venezuela’s oil reserves to how the nation can sustain and restructure its key export markets to transform potential into sustainable revenue.