An irony at hand

Dear Sir, since the end of 2023, the deposit interest rate has remained low while the amount of deposits keeps increasing. The phenomenon of “excess money” in banks appears, but at the same time, the banking sector still achieves record profits in the economy. Should we consider this as an irony and what does it reflect in Vietnam’s financial and credit markets?

Mr. Do Thien Anh Tuan. |

Mr. Do Thien Anh Tuan: The higher profitability rate of the banking sector compared to the average level of the economy is not a new story. This has been the case during the Covid-19 pandemic period and even now, when the economy is facing difficulties. Simply because even though the economy is sluggish and businesses are suspended, they still have to pay interest on their loans to banks.

The Government and the State Bank of Vietnam (SBV) have implemented some policies to support businesses such as debt rescheduling and debt extension, but these are not interest waivers or debt cancellations. If the Government does want to waive interest or cancel debt for businesses, it still has to find a way to compensate the banks for their profits since banks are in the business of money and are accountable to shareholders for profit targets. For state-owned commercial banks with the State as a shareholder, the Government can incorporate support policies, but this will also lead to much debate.

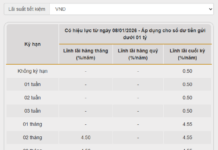

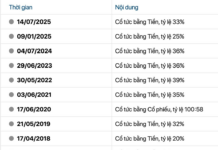

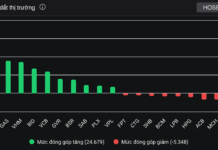

For Vietnamese banks, the main source of profit comes from credit, where the difference between deposit interest rates and lending rates determines the bank’s profit margin. Currently, the average profit margin of the banking system is high, clearly reflecting the sharp and rapid decline in deposit interest rates, while lending rates have decreased slightly and slowly.

In recent times, there has been a significant inflow of deposits into banks despite the low deposit interest rates. The reason is that people lack alternative investment tools, so depositing money in banks is a feasible option in the short term. Businesses with idle funds also do not have the need for reinvestment due to the uncertain economic prospects. The surplus savings in the short term have led to a sharp decline in deposit interest rates for many banks, except for weaker banks that maintain relatively high deposit interest rates to maintain liquidity and have the motivation to lend at high interest rates to offset risks.

Meanwhile, as mentioned earlier, many businesses with available funds either have not invested or have resorted to debt liquidation. Those businesses that want to borrow to survive either have to bear high interest rates or are unable to access capital.

Clearly, this is an irony in Vietnam’s financial market that has been discussed many times, indicating many shortcomings in the banking system and the capital market.

So, Vietnam’s economy has not entered a “low-interest rate” period as some optimistic views suggest, right? In your opinion, what are the reasons that make it difficult for businesses to access “cheap money” in the current context?

– First of all, to evaluate whether the money is “cheap” or not, we need to consider three aspects.

First, consider the real interest rate, not the nominal interest rate. If a business borrows with a nominal interest rate of 10% per year, but the inflation rate for that year reaches 8%, the real interest rate that the business has to pay is only 2%. Conversely, if the nominal interest rate is 5% per year, but the inflation rate is only 1%, the real interest rate is 4%. The cost of capital for businesses in the lower assumption is less than half compared to the higher assumption.

Currently, the projected inflation rate for 2024 by the National Assembly and the Government is about 4-4.5%. Therefore, if a business borrows with an interest rate of 10%, the real interest rate that the business has to pay will be approximately 5.5%. Clearly, this real interest rate is quite high compared to many countries in the region and the world. Vietnam’s economy will have difficulty maintaining international competitiveness when domestic businesses have to pay such high real interest rates.

Second, whether it is cheap or expensive depends on the borrower’s evaluation, here meaning each business, each industry, and the context of the economy. Each business, each industry, and each economy will have different business conditions reflected in the indicator called the return on investment or profit rate of capital investment.

It is difficult to calculate the average return on capital in the economy, and each industry and each project usually has a different return rate. Therefore, a business considering borrowing will have to compare the capital cost with the return rate of capital to decide whether the project is cost-effective.

Recently, we often talk about businesses that do not have the need to borrow instead of banks not wanting to lend. This is true because no bank raises funds and then refuses to lend. If a particular bank does not want to lend, it is because the customer is not suitable for the bank’s risk appetite or the bank itself prioritizes capital for symbiotic relationships with businesses, such as the case of SCB.

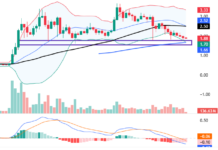

The fact that businesses are not borrowing shows that the expected rate of return on investment is decreasing while the cost of borrowing is not correspondingly decreasing. 2023 was considered the most difficult economic year since after Covid-19, with over 172,000 businesses leaving the market. According to the law of supply and demand, at some point, interest rates for borrowing will have to decrease. However, depending on the characteristics of the capital market or the stickiness of the financial market, the interest rates for borrowing may decrease rapidly or slowly and to what extent.

In recent times, we have seen a significant decrease in deposit interest rates, and the return rate of capital investment has also decreased. However, the interest rates for borrowing, although reduced, are still relatively high. This indicates that Vietnam’s financial market is not efficient, and borrowing interest rates are inflexible.

The third issue is the issue of risk. Typically, banks will lend at high interest rates to compensate for risks. High-risk businesses usually have to borrow at high-interest rates. This is unavoidable.

However, there are two issues here. First, there are risks specific to businesses or industries, but there are also systemic risks due to the business environment, policy environment, or potential macro risks. In the case of systemic risks, the role of the Government is to reduce these risks to help reduce risks for businesses, including their bank loans. As long as the business and policy environment are still considered high risks, it will be difficult for businesses to find “cheap money”.

Secondly, due to asymmetry information, high-interest borrowing from banks unintentionally leads banks to choose high-risk borrowers instead of low-risk borrowers. While some banks have tried to screen out high-risk customers, the Government’s role in reducing information asymmetry is also essential, through standards and requirements for transparency and disclosure of information.

So in this context, according to you, how can businesses have more stable and long-term access to “cheap money”? If so, what is the fundamental issue that needs to be resolved?

– To have “cheap money” immediately, one way is that the SBV will reinject capital at “cheap” interest rates to commercial banks so that they can lend at lower interest rates as committed to the capital reinjection terms.

However, this policy faces two short-term challenges. First, many banks currently have excess funds and do not need to borrow capital from the SBV to lend again. Moreover, lending by designated address could put banks in debt collection risks and require explanations, making it difficult to encourage banks to participate in lending. In practice, some interest support packages from the Government have not been implemented for this reason.

Secondly, the SBV is also cautious about injecting money due to inflationary pressures. It can be said that the SBV has never been put in a situation of multi-target monetary policy operation with many challenges like it is facing now.

However, the SBV can pursue the goal of reducing interest rates by promoting a healthy, competitive, and efficient money market. Here, I mean that barriers that increase transaction costs need to be removed. An efficient money market allows borrowers to have rights and tools to restructure their debt through market mechanisms. When interest rates go down, businesses naturally have the desire to restructure their loans to reduce costs. However, due to certain reasons, this cannot be implemented.

First, banks set terms and conditions that favor themselves and restrict the rights of businesses in credit contracts. This means that when deposit interest rates increase, lending rates will immediately be adjusted upwards, while deposit interest rates decrease, there are many reasons for banks to delay the adjustment of lending rates. Although they are contractual agreements, due to the weak competition of the banking system, the SBV needs to enhance supervision and timely regulate these contracts without leaving them to self-regulate in the market.

Secondly, when a business wants to repay a loan early to borrow new loans at lower interest rates, it faces the barrier of prepayment fees. Currently, the prepayment fees range from 2-3%, and some banks even charge up to 5%, which is very high. The reason for the prepayment fee is to help the bank reduce the risk of reinvestment. However, this risk has been inflated and abused. In the context of declining interest rates, to retain customers, banks have two options: reduce interest rates or increase prepayment fees.

Option 1 – reducing interest rates – is the goal of the SBV, but due to the unlimited option 2, banks will choose option 2. Therefore, the SBV needs to monitor and regulate this fee to prevent abuse. When the bank can only choose option 1 to retain customers in a competitive environment, interest rates will become more flexible according to market signals, giving businesses more opportunities to find alternative “cheap money”.

The underlying principle and resolution

What is your opinion on the set target of credit growth in 2024 being 15%? What is the most important factor in this story, sir?

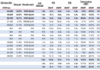

– At the year-end meeting of 2023, the National Assembly set the target for GDP growth in 2024 at 6-6.5% and inflation at 4-4.5%. Therefore, the nominal GDP growth is about 10-11%. Therefore, the growth rate of M2 money supply (the total value of money in circulation in the economy) is likely to be around 11% if the velocity of money remains constant.

Over the past decade, the velocity of money in Vietnam has continuously declined, indicating that the effectiveness of the monetary system is decreasing. This also shows the absorption capacity or productivity of capital is decreasing in the long run. The increase in money supply is related to credit growth and changes in official foreign exchange reserves. In 2023, the total money supply increased by about 10%, while credit increased by 13.5%. In 2024, after calculating the need to balance the monetary supply for the exchange rate policy, the technical capability to achieve the 15% credit growth target is within the grasp of the SBV.

Dear sir, at this time, should we raise the issue of businesses having stable and long-term access to “cheap money”? If so, what is the fundamental issue that needs to be resolved?

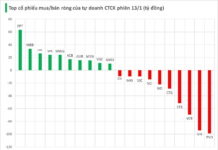

– The important issue is not how much credit growth should be but the quality of credit growth. If credit growth of 15% mainly flows into non-production channels such as real estate speculation, gold trading, and stock market speculation, it will not contribute to economic growth and job creation. Moreover, it will increase macroeconomic instability, add inflationary pressures, and shift economic costs to the real economy.

Currently, speculative activities are absorbing a significant amount of capital from the economy. The phenomenon of banks lending to entities in the form of cross-ownership groups may not only occur at SCB. The SBV needs to calculate the amount of credit flowing into speculative areas like this, and the Government needs tools to regulate and control these speculative activities, such as credit restrictions and taxation on speculative transactions.

When a significant amount of capital flows into speculative activities, the allocation of capital to real productive businesses decreases. Therefore, real businesses have to compete for capital at higher interest rates. Furthermore, speculative investors often accept higher borrowing interest rates due to the higher expected return rates of their speculative activities and the risk premiums. On the other hand, real businesses usually have lower, more stable profitability according to their industries and investment projects, with lower average risk levels. Therefore, they cannot compete with high-interest rates to borrow.

However, due to the drag and competition effects, real businesses still have to pay interest rates equivalent to speculators. If these businesses accept borrowing at high-interest rates, they are either under pressure and forced to borrow or will eventually engage in speculation. Businesses operating normally are unlikely to borrow at such high-interest rates when the return rate of capital is decreasing in difficult economic conditions.

To sum up, as long as there are speculators accepting borrowing at high-interest rates, regular businesses will still have difficulty accessing capital, and borrowing interest rates will remain high. The “low-interest rate” dream is only a reality when we can effectively control speculative activities in the economy and thoroughly deal with weak banks.

Hoang Hanh