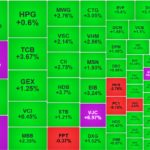

The market witnessed bottom-fishing efforts below the 1500-point mark of the VNI, marking the third session hovering around this level, despite a gradually weakening momentum. The formation of a base at this level remains uncertain, with liquidity showing signs of weakening.

A notable change to observe at this point is the breadth, as long as declining stocks outnumber advancing ones, the extent of specific losses will continue to mount, even if the index is propped up. Currently, the market liquidity is excessively high, leading to potential disputes between supply and demand. However, buying momentum is likely to wane over time.

The primary reason for this is that investors who have exited their positions will be hesitant to re-enter immediately. The market has just gone through an unusually lucrative phase, with exceptionally high short-term profits. As a result, the market needs time to stabilize. Satisfied investors will take a break and observe, while more ambitious ones will attempt to catch the bottom. This psychology commonly surfaces during the initial phase of a corrective phase, as the “theory” in a bullish trend suggests that every dip is a buying opportunity. It is only when the most enthusiastic buyers retreat that the weight of stocks will gradually exert its influence.

The matched transaction liquidity of the two exchanges dropped slightly by 13% compared to the previous session, reaching 40.2k billion excluding large deals. This is the lowest level this week but still significantly higher than the average. For instance, the average matched transaction liquidity during the three weeks prior was around 34k billion per session. If we compare it to the pre-July period, the current liquidity level is even higher.

The biggest hope now is that the robust liquidity within the market will not remain dormant. Bottom-fishing activities have been very dynamic since the “collapse” on July 29th, and every deep dip has been pulled back towards the end of the session. If this liquidity is strong enough to stabilize prices and form a consolidation base, there is a prospect of the market moving sideways. However, supportive information is currently scarce, and the market has already priced in all expectations, including earnings results.

The new information today is that the US will impose taxes across the board from August 1st, and Vietnam has yet to finalize negotiations, resulting in a 20% threshold. While this rate is not exceptionally high or low, it is somewhat unfavorable compared to some other countries that have concluded negotiations. Nonetheless, this tax rate falls within normal expectations. Unless there are unexpected details regarding technical aspects, the market has already factored this in. In the coming days, the market awaits more comprehensive information on the new rules of origin.

I maintain the view that the market is undergoing a normal short-term correction. While price dips present buying opportunities, there is no need to rush. A prolonged uptrend necessitates a correspondingly prolonged corrective phase, which cannot be resolved within a few sessions. A new “setup” for a fresh campaign requires time, and more crucially, the resolution of lingering uncertainties and the establishment of forward-looking expectations.

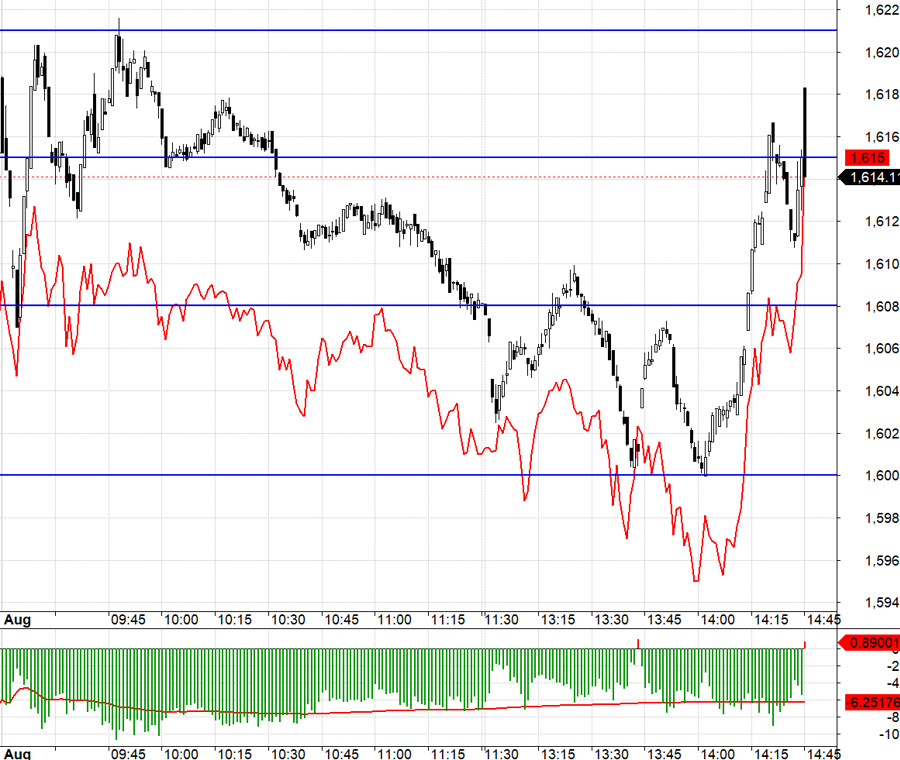

The derivatives market today started to price in a wider range for the potential downside. The VN30 index fluctuated between 1615.xx and 1621.xx before 10:30 am, with F1 futures contracts averaging a discount of nearly 8 points. When the VN30 index broke below 1615.xx, the high probability scenario was a drop to the two range-bound regions, presenting a good opportunity for short positions. However, the main risk was the -8-point basis. Unless the basis is maintained, this differential needs to be cautiously considered as the range boundary is exactly equal to this differential. Fortunately, the large-cap stocks exerted positive pressure, and despite the narrowing basis, the VN30 index still managed to touch 1600.xx in the afternoon session.

With signs of bottom-fishing efforts slowing down, the market is likely to continue its corrective phase and may even test supply and demand by expanding the trading band. While the last three sessions have been relatively stable with supportive demand, the losing positions and external liquidity have yet to be tested during sessions with more significant pressure. The strategy is to wait for lower prices to buy, employing a flexible long/short approach with derivatives.

VN30 closed at 1614.11. The nearest resistances for the next session are 1621, 1632, 1639, 1652, and 1662. The nearest supports are 1610, 1600, 1591, 1582, 1572, and 1561.

“Blog chứng khoán” reflects the personal views of the author and does not represent the opinions of VnEconomy. The views, opinions, and investment advice presented are solely those of the author, and VnEconomy respects the author’s perspective and writing style. VnEconomy and the author are not responsible for any issues arising from the investment opinions and recommendations presented in this blog.

“Blue-Chip Stocks Surge: VN-Index Recaptures the 1,500-Point Milestone”

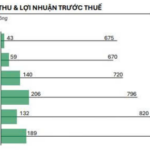

Despite a significant decline in liquidity, today’s session witnessed an exuberant market performance. The largest blue-chip stocks witnessed a robust surge, propelling the VN-Index not only to reclaim the 1500-point mark lost last week but also to surpass 1528.19 points, reigniting hopes of testing the historical peak once again.

The Flow of Capital: The Rhythm of Adjustment Endures

The market has experienced its most significant correction since the April lows, following a remarkable 42% surge in the VN-Index. The abrupt 4.1% decline on July 29, accompanied by record-breaking trading volumes, signaled the conclusion of a short-term cycle. It’s essential for the market to cool off and consolidate before embarking on the next upward trajectory.