Legendary Investor Stanley Druckenmiller

|

Born in 1953, Stanley Druckenmiller is a legendary investor with an average annual return of over 30% for three decades. What’s even more astonishing is his unparalleled consistency—he has never experienced a losing year throughout his entire career.

Druckenmiller rose to public prominence as George Soros’s deputy at Soros Fund Management, famously architecting the 1992 short-selling strategy against the British Pound and Italian Lira. This move netted a staggering $2 billion in profits within weeks.

But even an invincible player like him isn’t immune to mistakes—what was his most unforgettable blunder?

At a January 15, 2015, investment forum held at Florida’s exclusive Lost Tree Club, the typically reserved Druckenmiller opened up about his most memorable failure. It’s a story every investor can relate to.

Moderator: What was your biggest mistake, and what lesson did you take from it?

Stanley Druckenmiller: I’ve made countless mistakes, but one stands out as truly astonishing. It’s almost comical in hindsight—at least 15 years later, now that the pain has faded.

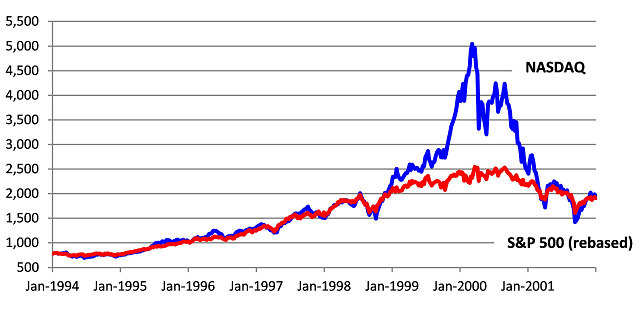

In 1999, after Yahoo and America Online’s stock prices had surged tenfold, I had a brilliant idea at Soros Fund: short internet stocks. I built a $200 million position between February and mid-March. That short cost me $600 million, completely wiped me out, and left the portfolio down 15% cumulatively that year.

I took immense pride in my streak of never having a down year. I thought it was over.

Then something shifted—I can’t recall if I visited Silicon Valley or spoke with a 22-year-old autistic boy. But whoever it was convinced me the tech boom was just beginning.

I hired a few “gunslingers”—we only knew IBM and Hewlett-Packard back then. Now I needed Veritas and Verisign. With these new hires, we ended the year up 35%, reversing from a 15% loss. Nasdaq had soared 400% by then.

In January 2000, I walked into the office and declared we’d sell every tech stock—everything. They were trading at 104 times earnings (P/E ratio). We’d sit out and wait for the next opportunity.

I didn’t fire the gunslingers. Their allocation was too small to harm the fund. But they started making 3% daily, driving me insane. Their small account was up 50% that year, while our main Quantum Fund only rose 7%.

By March, I felt it coming. I just had to get back in. I couldn’t resist.

Three times a week, I told myself, “Don’t do it.” But eventually, I picked up the phone and bought $6 billion in tech stocks. Six weeks later, I left Soros Fund, having lost $3 billion on that trade alone.

What did I learn? Nothing. I knew I shouldn’t have done it, but I couldn’t control my emotions. Maybe the lesson is not to let it happen again—though I already knew that.

|

NASDAQ vs. S&P 500 (1994-2001)

Source: Internet

|

Druckenmiller’s mistake isn’t unique—it’s a common pitfall for investors. Emotions and greed cloud judgment, impairing decision-making. Controlling one’s psyche is far harder than it sounds.

For those who think it’s not that difficult, consider the context of Druckenmiller’s error. He wasn’t a novice—he was a 24-year market veteran, already a legend.

– 12:00 05/10/2025