Net Zero pledges are becoming increasingly common, yet actual actions lag behind. The latest report from the NewClimate Institute warns that corporate commitments are only about one-third of what’s needed for the 1.5°C goal. Instead of drastic cuts, many businesses opt for easier paths: using accounting tricks to embellish emission figures.

Net Zero on Paper: How Creative Carbon Accounting Distorts Climate Commitments

The race to Net Zero faces risks of manipulation by numbers. UNEP’s report highlights that the world must cut 42% of greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 from 2019 levels to maintain the 1.5°C target[1].

However, the NewClimate Institute and Carbon Market Watch report a grim reality: 51 major corporations, emitting 8.8 billion tons of CO₂ (16% of global emissions), pledge only a 30% average reduction by 2030[2]. This gap between promises and actions spawns a troubling phenomenon: creative carbon accounting.

Creative carbon accounting isn’t outright fraud. It’s a sophisticated blend of exploiting loopholes in reporting standards, manipulating data in regulatory gray areas, and greenwashing tactics to beautify emission figures without real reductions.

Pressure from investors and global supply chains forces companies to “green” their reports. As ESG scores influence stock pricing and major funds like BlackRock or Vanguard demand climate transparency, the motive for data manipulation intensifies.

The core issue lies in the GHG Protocol’s three emission scopes.

Scope 1 covers direct emissions from production; Scope 2 covers indirect emissions from purchased energy; while Scope 3 (emissions from the entire value chain) is the most manipulable. It accounts for over 90% of analyzed companies’ carbon footprints in the NewClimate Institute’s report but is the hardest to measure and often overlooked.

The report’s assessment shows only 8 out of 28 companies have emission reduction targets rated “high” and “reasonable” in comprehensiveness, including relatively clear Scope 3 commitments[3]. This means most companies still lack robust targets for their most significant emission source.

International standards like TCFD and IFRS S2 aim for greater transparency. Effective January 2024, IFRS S2 requires companies to disclose climate risks affecting cash flows and capital costs. However, these standards inadvertently create gray areas by allowing companies to choose calculation methods, base years, and reporting scopes. These choices can significantly alter final emission figures.

The OECD’s 2024 report warns of rising greenwashing risks due to methodology opacity and data gaps. It emphasizes that green financial figures must be contextualized within overall capital flows, not just reported in isolation.

The OECD also calls for supplementary indicators, full disclosure of calculation assumptions, and ensuring data inputs are reliable and comparable. Ultimately, assessments must rely on credible, widely recognized reference standards[4].

Dissecting “Virtual Emission Reduction” Tactics

The voluntary carbon credit market, projected to reach $50 billion by 2030, is becoming a tool for greenwashing[5]. A large-scale study published in Nature Communications in November 2024 analyzed data from 65 studies and 2,346 carbon credit projects. The findings are alarming: less than 16% of issued carbon credits represent actual emission reductions.

Specifically, for REDD+ projects, the study estimates only about 25% of issued credits have real impact[6]. Many companies buy credits from already profitable renewable energy projects or forests not at risk of deforestation.

Virgin Atlantic’s Oddar Meanchey program in Cambodia is a prime example. Fern revealed ongoing deforestation, reversing previous emission offsets. Similarly, MIT Technology Review and ProPublica found Massachusetts Audubon Society earned credits for conserving forests never at risk of logging, bought by companies like Shell and Phillips 66[7].

Scope 3, emissions from the value chain, is the biggest “black box.” CDP’s report shows only 25% of companies integrate supply chain climate risks into management. Supply chain emissions average 26 times direct operational emissions, yet only 15% set upstream reduction targets[8]. The complexity of GHG Protocol’s 15 categories allows companies to exclude high-carbon suppliers or use generic emission factors instead of actual data.

Base year manipulation is another tactic. Companies can choose a year with unusually high emissions as the baseline, making subsequent reductions appear more impressive. While SBTi requires recent, reliable base years, there’s no strict monitoring to prevent abuse. Some companies recalculate base years after structural changes without fully disclosing assumptions and adjustment methods[9].

Selling high-emission assets is another “cleaning” strategy without global emission reduction. A company can divest a coal-fired power plant, making the parent company’s report look cleaner, but total emissions remain unchanged as the plant operates under a new owner. NewClimate Institute notes companies increasingly rely on “wrong solutions” like carbon capture and renewable energy certificates instead of real reductions. Its 2024 report shows no company among the 51-55 evaluated achieved “high integrity.”

Danone, Iberdrola, Mars, and Volvo Group have relatively good reduction plans, while H&M, Nike, and Inditex lack specific plans to meet targets. Walmart hasn’t updated targets since 2016, and Volkswagen dropped its 2025 interim target without replacement[10].

Who Enables Opaque Data?

Third-party verification systems, meant to be the last defense against greenwashing, show serious weaknesses. Auditors often can only verify data provided by companies, lacking tools and authority for independent emission source checks.

The issue is more severe with Scope 3, where data depends on hundreds or thousands of supply chain providers. Many verification firms specialize in traditional finance but lack deep climate science expertise, emission measurement technologies, or complex GHG Protocol methodologies.

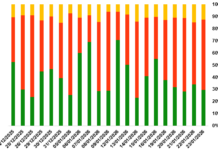

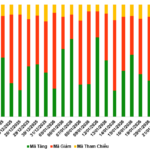

Inconsistency among ESG rating agencies creates confusion for investors. MIT Sloan’s research shows correlations between ESG scores from six major agencies (MSCI, Sustainalytics, Moody’s ESG, S&P Global, Refinitiv, KLD) range from 0.38 to 0.71[11]. Analysis reveals 56% of differences stem from measuring the same attribute with different indicators, 38% from including/excluding different factors, and only 8% from different weights. A company might score high with MSCI but low with Sustainalytics, leaving investors unsure which data is reliable[12].

In Europe, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), effective January 2023, requires large companies to disclose information under the “double materiality” principle and undergo third-party audits. CSRD mandates third-party audits and reporting under European Sustainability Reporting Standards. However, the European Commission proposed a simplification package in February 2025, reducing compliant companies and mandatory data points, indicating enforcement challenges[13].

In the U.S., the SEC adopted climate disclosure rules in March 2024, requiring public companies to disclose Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions if “material.” Scope 3 was removed from the final rule. By March 2025, the SEC announced halting defense of these rules, marking a significant shift in its approach[14].

In Vietnam, Decree 06/2022/NĐ-CP on greenhouse gas mitigation and ozone protection established a national MRV system. It applies to facilities emitting over 3,000 tons CO₂ equivalent/year, including thermal power plants, industrial facilities consuming over 1,000 tons oil equivalent energy, freight companies, and large commercial buildings[15].

Decree 119/2025/NĐ-CP specifies formats, timelines, and greenhouse gas inventory procedures, establishes a technical expert review board, and requires facilities to work with certified third-party verifiers[16].

Rebuilding Trust

The international community aims for a “common carbon accounting standard,” akin to GAAP or IFRS in finance. ISSB has issued IFRS S2, integrating TCFD recommendations. However, global uniform adoption remains a long journey.

Emerging digital MRV (measurement, reporting, and verification) systems are transforming climate outcome tracking through automation and real-time validation. The World Bank’s CMI WG emphasizes the need for a level playing field for DMRV.

Satellites and AI provide independent monitoring. Remote sensing accurately measures forest carbon stocks for REDD+ projects. NASA and other agencies’ satellites detect methane leaks. AI and machine learning analyze large datasets to improve MRV accuracy and efficiency.

Blockchain creates an immutable, transparent ledger for carbon credits. As registries build on this technology, market participants can view every credit’s digital history. Smart contracts automate issuance and trading, and combined with digital MRV tools, provide real-time visibility into carbon sequestration efforts.

In Vietnam, Decision 232/QĐ-TTg approved the Carbon Market Development Scheme. The pilot phase runs from June 2025 to late 2028 with many large emitters participating. From 2029, the market will operate officially. Vietnam is also promoting cooperation under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. According to OPIS, Singapore has “substantially completed negotiations” with Vietnam on Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes (ITMO), allowing countries to transfer emission reduction results to help others meet national climate goals (NDCs)[17].

Market pressure will be the strongest driver. Global funds and brands demand detailed carbon data from suppliers. CDP reports its Supply Chain Program has helped reduce 43 million tons of emissions—more than Sweden’s annual emissions[18].

The fight against creative carbon accounting is urgent for global sustainability. Every hidden ton of CO₂ is a step back in the race against climate change. As digital MRV standards advance, technology enables real-time monitoring, and investors demand absolute transparency, the era of “Net Zero on paper” is ending. The question remains: Will action be timely enough before the 1.5°C goal becomes unattainable?

[1] https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/2025-01/egr2024.pdf

[2] https://newclimate.org/sites/default/files/2024-08/NewClimate_CCRM2024.pdf

[3] https://newclimate.org/sites/default/files/2024-08/NewClimate_CCRM2024.pdf

[4] https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2024/12/aligning-finance-with-climate-goals_6b70b161/aa7c23b2-en.pdf

[5] https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/sustainability/our-insights/a-blueprint-for-scaling-voluntary-carbon-markets-to-meet-the-climate-challenge

[6] https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-024-53645-z

[7] https://earth.org/is-carbon-offset-a-form-of-greenwashing

[8] https://supplychaindigital.com/sustainability/cdp-report-scope-3

[9] https://senecaesg.com/insights/choosing-the-right-baseline-year-a-critical-move-for-corporate-climate-action

[10] https://grist.org/accountability/corporate-climate-plans-are-improving-but-still-critically-insufficient

[11] https://academic.oup.com/rof/article/26/6/1315/6590670

[12] https://mitsloan.mit.edu/sustainability-initiative/aggregate-confusion-project

[13] https://www.dechert.com/knowledge/onpoint/2025/3/european-commission-proposes-simplification-of-the-csrd-and-cert.html

[14] https://www.sweep.net/blog/sec-ends-defense-of-climate-disclosure-rules

[15] https://www.perplexity.ai/search/ban-la-mot-nha-bao-kinh-te-ky-dAlU5EkKQfm_Da0wp2v1BA

[16] https://vn.andersen.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Vietnam-New-Decree-Amending-Regulations-on-Mitigation-of-Greenhouse-Gas-Emissions-and-Protection-of-the-Ozone-Layer.pdf

[17] https://www.opis.com/resources/energy-market-news-from-opis/singapores-first-article-6-carbon-credit-tender-draws-223-million-top-bid

[18] https://www.cdp.net/en/insights/strengthening-the-chain

– 12:00 15/11/2025

Why Banks Are Abandoning Climate Commitments in Droves

The UN-backed Net-Zero Banking Alliance (NZBA) has officially disbanded, marking the end of a symbolic era in global finance’s fight against climate change. However, experts argue that this dissolution is not a retreat but rather a pivot toward more effective strategies in addressing environmental challenges.

Vietjet and Oxford University Unveil Landmark Aviation Initiative, Witnessed by General Secretary Tô Lâm

General Secretary Tô Lâm and Professor Irene Tracey, Vice-Chancellor of the University of Oxford, witnessed the exchange of documents between Vietjet’s Deputy CEO Hồ Ngọc Yến Phương and Professor Myles Allen, Director of the Oxford Net Zero Centre, announcing the results of the Net Zero Carbon research project.

Major Emitters Initiate Greenhouse Gas Inventory Implementation

Mr. Nguyen Tuan Quang, Deputy Director of the Department of Climate Change (Ministry of Agriculture and Environment), announced that programs aimed at green energy transition, reducing carbon and methane emissions are underway. Major emission sources have begun conducting greenhouse gas inventories in compliance with national regulations.