This article reflects the views of author Kaushik Basu

The global economy is undergoing a qualitative shift

This year’s conference emphasized the need to reassess the state of the global economy. The rapidly escalating debt crisis in the Global South, while not the direct focus of the conference, was a matter of concern for many scholars.

The IEA was established in 1950, with Joseph Schumpeter as its first chairman. Since then, the organization has been led by some of the world’s most renowned economists, including Paul Samuelson, János Kornai, Kenneth J. Arrow, Amartya Sen, and Joseph E. Stiglitz.

This year’s conference highlighted major challenges to the global economy such as supply chain disruptions related to the Russia-Ukraine conflict, the lingering effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the tense situation in the Israel-Hamas conflict.

(*) Global South: includes South America, Africa, and most Asian countries.

As the global economy undergoes a qualitative shift, the core assumptions in economists’ models also need to change. It is not surprising that many speeches at this year’s conference focused on the impact of digital technologies and social media on labor, wages, and inequality. Other speakers focused on the changing nature of globalization, the transition from a unipolar economic order to a multipolar one, and the decline of democratic institutions in the context of resurgent nationalism.

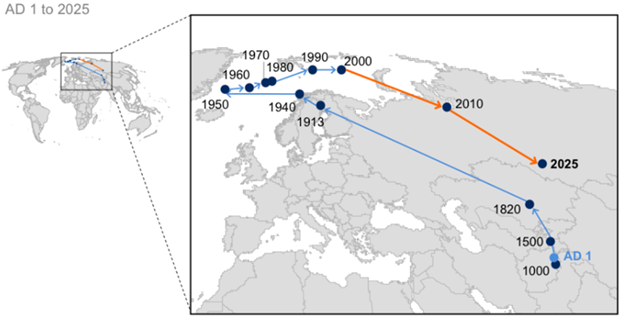

The center of the world economy will shift to Asia

Danny Quah’s presentation showed the future outlook for the global economy. Based on previous research by Jean-Marie Grether and Nicole A. Mathys, as well as his own, Quah illustrated the shifting center of the world economy. He noted that in 1980, this center was situated between the North Atlantic, reflecting the dominance of North America and Western Europe during that period.

The process of shifting the center of the world economy

Source: Analysis by the McKinsey Institute, using data from Groningen University

As the economies of East Asia rise, the global economic center begins to shift from the West to the East. Quah estimated that by 2008, it had moved close to Izmir, Turkey, and continued its eastward shift due to the rapid growth of the Indian and Chinese economies.

He predicts that by 2050, the world economic center will be located between India and China. This opens up opportunities but also gives rise to geopolitical and political tensions.

Increasing inequality

The rise of populism is partly due to increasing domestic inequality and declining social mobility, as Adam Szeidl pointed out in his speech. However, the trend of supporting right-wing leaders by Western voters is perplexing, as their favored policies might exacerbate the issues they seek to address.

The greatest threat comes from developing countries

Despite bleak predictions of a prolonged recession, the global economy successfully avoided a recession in 2023, thanks to strong GDP growth and unexpected job creation in the United States. While this has led some economists to cautiously express optimism for 2024, I believe such complacency is misguided.

This optimism may be due to the tendency of analysts to focus on wealthy countries when assessing the state of the global economy. A more detailed analysis would paint a more gloomy picture of the global economic landscape. Unlike the Great Recession of 2008-2009, which was caused by the collapse of the U.S. housing market, the biggest threat to global economic stability now comes from developing countries.

In the COVID-19 pandemic, almost every country in the world was forced to increase public spending. But while developed and middle-income countries have the resources to purchase vaccines, medicines, and supplies, low- and lower-middle-income economies are borrowing heavily to cope with the pandemic as well as subsequent food and energy crises. This has left many countries in a debt crisis or at a high risk of debt distress, highlighting the need for specific consideration of developing countries.

According to the latest International Debt Report by the World Bank, the world’s poorest countries are the hardest hit by the sovereign debt crisis. Their external debt, at an all-time high of $88.9 billion in 2022, is predicted to rise by a further 40% by 2024. Ghana and Zambia have already defaulted, Ethiopia may default by 2024, and domestic debt in countries like Argentina and Pakistan is alarmingly high.

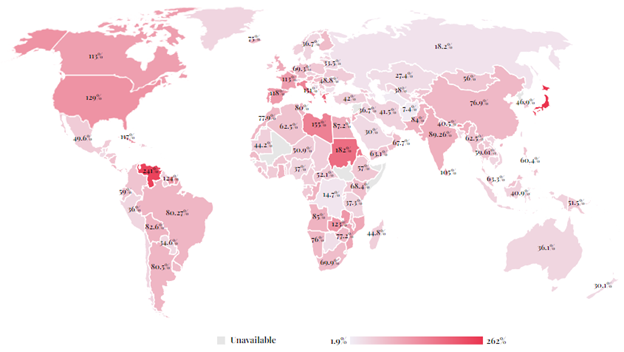

Sovereign debt-to-GDP ratios by country in 2023

Source: Wisevoter

Writing about this is not enough. We need urgent international intervention to prevent the situation from escalating. While the current crisis may not have an immediate global impact like the subprime mortgage market collapse in the U.S. in 2008, its long-term implications could be far-reaching. Notably, it could exacerbate the refugee crisis, further fuel the rise of right-wing populism in developing countries worldwide.

While the 5-day IEA Congress in Medellín feels like a breath of fresh air, addressing the debt crisis in developing countries requires more than in-depth research. The international community, especially multilateral organizations like the World Bank, must take decisive action before the situation spirals out of control.

About the author Kaushik Basu

Kaushik Basu is a former Chief Economist of the World Bank and Economic Adviser to the Government of India. He is also Professor of Economics at Cornell University and a Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution.

Source: Cornell University Marketing Group

![[Photo Essay]: Experts, Managers, and Businesses Unite to Forge a Path Towards Sustainable Green Industry](https://xe.today/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/z678592918-150x150.jpg)

![[Photo Essay]: Experts, Managers, and Businesses Unite to Forge a Path Towards Sustainable Green Industry](https://xe.today/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/z678592918-100x70.jpg)